As I rummaged through my grandmother's basement, I realised my lifelong fascination with records had finally led me here. I wasn't under any illusions that I would uncover a lost recording by Bessie Smith or some other blues legend (this was my grandmother after all), but the sheer mystery of what sounds might lurk in her stack of fragile 78 rpm records became all-consuming. What I found were the expected popular big band dance tunes, but also a number of sides by a name I already knew: Wilf Carter, aka Montana Slim, Canada's yodelling cowboy, and one of our nation's first big musical exports. There was a record by someone named Jesse Crawford called "At Dawning," a product of the Victor Talking Machine Co. of Canada, described as "solo for pipe organ." As I held it, something in the grooves demanded to be heard. Of course, with no turntable that had a 78 setting, another step was required first: I needed a gramophone.

The zealousness I experienced at that moment has been shared among 78 collectors since the 1950s when the recording industry switched from pressing records on shellac a valuable commodity during the Second World War to vinyl, a more durable and practical surface for the emerging LP and 45 markets. This commercial sea change also brought about a change in music itself; new, progressive forms, like rock'n'roll and cool jazz caught the public's imagination, replacing the archaic sounds most associated with the 78 era. The music industry embraced new technology, almost immediately leaving the historical preservation of the 78 legacy to collectors. While the 78 itself may be virtually extinct today, those who have preserved what copies do exist have continually seen their efforts pay off through the influence that some neglected artists have had on contemporary music.

There's no better example than Mississippi Delta bluesman Robert Johnson; the 29 sides recorded during his brief lifetime became prized by collectors for their musical quality. Through the efforts of independent collectors, Robert Johnson became a legendary influence on early rock'n'roll; his place in the pantheon was assured with the CD release of a pristine-sounding 1990 box set that collected his entire recorded output. For most collectors, it was the point at which he ceased to be a ghost and they moved on to more pressing mysteries that needed to be solved.

Jack White clearly has a thing for ghosts; references to them are peppered throughout the White Stripes' catalogue. He has done his part in keeping the ghosts alive by covering songs by Son House and Blind Willie McTell, artists that, by all rights, should have no connection to a middle-class kid who grew up in Detroit in the 1980s. But for more and more people like White, this land of ghosts the "old, weird America," as critic Greil Marcus put it is far more real than any music currently being made.

Most master recordings from this period have been lost, neglected or destroyed; it has been left to the self-styled musical archaeologists to scour attics, basements, and warehouses for more pieces to this never-ending puzzle. In many cases, this has led to collectors starting their own reissue labels, creating a separate industry and in some ways, an alternate history. Robert Johnson's more rough-edged predecessors of the 1920s are now most blues collectors' ultimate goal. The same goes for country music Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family no longer hold the same allure as the more "authentic" musicians who emerged from the backwoods of Tennessee and Virginia at a time when companies would record anyone who could bang out a tune on a banjo or fiddle.

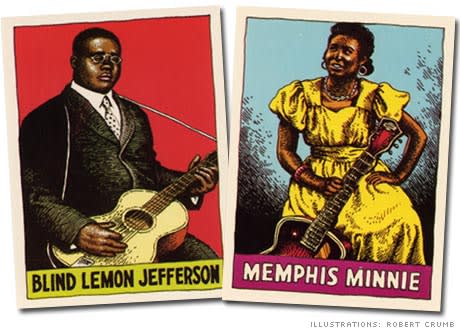

Much of this critical shift has been helped along through the personal tastes of such high-profile figures as White, Bob Dylan and artist Robert Crumb. Crumb especially has had a profound influence since the acclaimed 1994 documentary about his life fully illuminated his obsession with 78 collecting and old time music's ongoing hold on his psyche. In fact, the best introduction to the music is still Crumb's series of blues and country "trading cards" that provide bios of his favourite artists.

The current revival in old time music can in many ways be traced to the reissue of Harry Smith's Anthology Of American Folk Music by Smithsonian/Folkways in 1997. Smith is the patron saint of 78 collectors, having had the vision to gather as many sides as he could during WWII before the shellac could be melted down. But Smith's real genius was to sift through those hundreds of old blues and country records and construct a personal-yet-unifying glimpse of an already bygone era.

When the Anthology first appeared in 1952, it was a cultural dividing line, spawning a new generation of artists Dylan among them whose styles were almost solely based around the music Smith had single-handedly preserved. Since its reappearance, the Anthology has accomplished this feat again in the alt-country world. The recent stripped-down, spooky efforts by The Be Good Tanyas, Neko Case, Elliott Brood, and even Tom Waits, owe much to the subversive spell that the Anthology has once again cast.

"The Anthology was a huge touchstone," says Dean Blackwood of Revenant Records, the current leader in old time reissues. "It was Harry's approach his fundamental irreverence, his distrust of institutions and academics, his impishness, and his relentless intellectual and creative honesty that was equally if not more important to us in terms of setting a course for Revenant." The label's latest release is American Primitive Vol. II, a stunning collection of rare pre-war folk, some of which has long been prized by aficionados, such as Geeshie Wiley's "Last Kind Word Blues," and relatively new discoveries such as the NuGrape Twins, gospel singer Homer Quincy Smith, and female prisoner Mattie May Thomas. Blackwood founded Revenant with the late, celebrated guitarist John Fahey, whose passion for all forms of "raw musics" led to genre-crossing collections by the likes of Captain Beefheart, Albert Ayler and rockabilly pioneer Charlie Feathers. "Almost all the recordings were items that Fahey had shared with me at one time or another," Blackwood says. "Sometimes he planted a clue that I had to follow up on later in some cases, after his death such as a brief mention of the recordings from the sewing room of Parchman Farm [Prison] where Mattie May Thomas sang her special, baleful songs. I think it was just an offhand comment about how he loved Geeshie and Elvie [Thomas] above all other female blues singers, with the possible exception of Mattie May. That kind of thing can get the juices flowing; you can't get your hands on those recordings quickly enough."

Blackwood's involvement with the label is rooted in a childhood fetish for 78s, which grew during the early 90s while he was working at Sub Pop's East coast office and attending Harvard law school. "I always had an obsession with 78s since being introduced to them as a kid at my great grandparents' house in Lawson, Arkansas," he says. "By 1995 I had finished law school and was working at a law firm in Nashville, and on the heels of a 78 project with Fahey I began to manage' him and help him with various legal and non-legal things. He came into a small inheritance that year and, instead of investing it wisely, opted for us to start a new record label venture."

Even for a latecomer to the 78 scene such as myself, it's easy to share the distrust of institutions and academics that Blackwood speaks of. The personal obsessions of hardcore collectors have led to strong arguments that jazz was dead by 1933, the last great blues singer was Howlin' Wolf, and country went to the great beyond with Hank Williams. Although he is internationally known in rock circles, Jeff Healey is part of this crowd. His collection of 78s is estimated at 25,000, and his love of early jazz prompted the formation of his other band, the Jazz Wizards, in which he plays trumpet; he also hosts his own old-time radio program. With such a vast stock of records, it's not surprising that Healey also got the bug at an early age. "It started off with records in my family, mostly ones that my grandmother played me when I was young," he says. "By the time I was 11, I had about 500 records, from semi-classical and war tunes, to dance bands and country."

As Healey's tastes became more refined, it only increased his desire to find more of what he liked. "The moment that my dad first gave me records that he got from a second-hand store, I had my coat on wanting to go back and get more. From that point on, we went anywhere to find records."

My own fetish manifested itself when I set out to find a gramophone. On looks alone, they are beautiful art-deco relics worth owning; the oversized horn that provides amplification accentuates a room like a giant orchid. I knew it wouldn't be easy, so when an ad for two at reasonable prices appeared, it seemed like serendipity. One gramophone was a gorgeous, full-size living room model that proved too much for my needs. I opted for a more portable one that I could picture being taken out for Gatsby-esque picnics by white-linen-clad couples topped with straw hats and parasols. The seller explained the simple mechanism, with its turntable that required hand cranking like the engine of a Model T Ford, and emphasising that the needle must be changed with each record. This sounded excessive until I examined the needle, which appeared only slightly more durable than a sharp pencil.

Getting the gramophone was a major score, but I really wanted records. I haggled until he threw in a few of his own, one of which I broke as soon as I got home the reason vinyl was invented was precisely because shellac 78s are so fragile. One I managed to hold onto was a version of Kurt Weill's "September Song," sung by some kid named Sinatra in 1946. Then I played "At Dawning," and it was just as strangely moving as I had hoped a window into an innocent past, with the tinny sound only adding to the overall disconcerting effect. As audiophiles have asserted since the rise of compact discs, part of the lasting appeal of records lies in a subconscious love of hearing those cracks and pops.

By his late teens, Healey was being asked to donate records to reissue projects, which suddenly made him quality-conscious. "Being asked to participate is exciting, but the challenge becomes finding the highest-quality recording. In many cases, the major labels have access to the original metal masters, but they aren't able to do the necessary clean-up work properly. I find that if the restoration isn't done by a musician, or someone who at least knows the music well, then the original sound quality is always compromised."

Blackwood has similar concerns whenever a new Revenant release is being prepared, a process that lasts two or three years. "There is certainly software available to get rid of static, but this will come at the expense of the high frequency end of the music, so you end up with something that sounds like it's playing behind a closed door down the hall. You lose all those sparkling highs. When in doubt, leave it alone. More noise generally also means more music."

Digitalisation has undeniably reached a point where sound can be extracted from any source. The McGill Audio Preservation Project (MAPP) in Montreal is one example of science aiding in the process. Catherine Lai, a PhD student with the Project, agrees that the intrinsic aspects of the music must come first. "As organisations and institutions convert musical material into digital formats, the need for efficient workflow management tools will increase because the digitization process is time-consuming, expensive and requires much human intervention," she says. "For example, the British Library holds over 2.5 million sound recordings. Even with a conservative estimate of digitisation time at 30 minutes per recording, the total digitisation time required would be at least 1.25 million hours, or 142 years."

While Lai says that much of the research has involved determining the best analog-to-digital conversion system, MAPP's major contribution could be its use of optical scans. "There are tremendous advantages to preserving phonograph recordings as 2D or 3D images. Without touching the recordings themselves, which deteriorate upon playback, we can experiment freely with methods of converting audio to determine the best method."

On the night of this year's Mardi Gras, there was an unusual record release party at Toronto's Cameron House. On sale for $25 was a brand new 78 rpm recording by Miss Alex Pangman and Colonel Tom Parker of the Backstabbers, called "Dead Drunk Blues," with the proceeds going to Habitat For Humanity's New Orleans Musicians Village Project. "We're unapologetic in our love of these discs; we have about 2,000 between the two of us," Parker says. "I wrote the song last March, and after the devastation of Katrina, decided that we needed to help the city however we could."

The Katrina disaster recalled both the last great New Orleans flood, in 1927, and the original songs that chronicled it: Blind Lemon Jefferson's "Rising High Water Blues"; Memphis Minnie's "When The Levee Breaks"; Charley Patton's "High Water Everywhere." The ghosts continue to haunt us, as they do Dean Blackwood. "The idea that somehow this stuff is solely the province of those with the divine seal on their forehead, that one may therefore elevate one's own mission by impugning as impure the motives of others who may traffic in similar material, is a notion I don't share with certain other folks who fancy themselves the keepers of the flame. I do believe you have an obligation to do right by the work to bring to it an excellence of scholarship, sonics, and careful selection."

If you've ever purchased a compilation of old time blues or country, chances are some of it has come from the collection of Joe Bussard. His thorough work in finding rare 78s throughout rural areas in the Southeastern U.S. has made him the source of best-known-quality recordings for many reissues, including Revenant's Charley Patton box set, Screamin' And Hollerin' The Blues, and the restored Smith Anthology. Yet, he is also known for making tapes for anyone looking for a song that, more often than not, only he possesses. In a 1998 profile on Bussard for The Washington City Paper, the head of noted blues and folk reissue label Yazoo/Shanachie Richard Nevins stated, "The important thing about Joe Bussard is that he has disseminated the music more than anybody else on earth. He has preserved and popularised the music more than anyone, and he's done more for the music than anyone. All the institutions are bogus nonsense. They don't do any good at all."

Bussard built the bulk of his collection in the '50s and '60s, often going door-to-door to follow leads. His findings made him the envy of other collectors, including John Fahey, who became a close friend. Bussard was eventually compelled to start his own exclusively 78 label, Fonotone, which released Fahey's first recordings, Bussard's own group, Jolly Joe's Jug Band, and many others. A new box set from the Dust-To-Digital label tells the complete Fonotone story and gives Bussard his rightful due as the last pure old time music entrepreneur. Still, as long as his old time collection remains intact, those wishing to dip into it as Sony also did for last year's remarkable Charlie Poole box set, You Ain't Talkin' To Me will keep coming to him. "I'm not giving [my collection] to any of those [labels]," Bussard said in 98. "If you give it to them, they shove it back in some hole, and there it sits. It ain't no worry of mine. I don't expect to kick off that quick. I expect to be around another 20 years to enjoy it."

My first serious quest to expand my collection forced me back to the classifieds in search of anyone selling anything. One ad eventually appeared proclaiming "jazz and country 78s for sale." It was clearly a direct personal plea, and I got the guy on the phone right away. But he seemed a little hesitant, wanting to meet me in the parking lot of a nearby Tim Horton's. I made sure to arrive early, and recognised my man the moment a well-driven 70s land shark pulled up to the front window. As I made eye contact with the twitchy older fellow, he wasn't eager to come in for coffee, so I went out and introduced myself. He didn't waste time getting down to business, pulling stacks of 78s out of his back seat, and showing me more in the trunk. I could only guess what people passing us must have been thinking, as I tried to digest his detailed descriptions of each record while making my picks. Sensing I was in over my head, I ended up giving him $50 for as many records as I could carry several Hank Snow and Roy Acuff sides among them and we both went away happy. I've since seen him on other occasions peddling his wares at used record stores around town. He never remembers me.

After that initial success, it's been hard to find 78s of real quality, but the need to dig will never go away. Even for long-time collectors, there are things yet to be found. But as Blackwood admits, nowadays this is largely left up to fate. "I'm amazed every time something surfaces, to tell you the truth," he says. "The recent Blind Joe Reynolds record that surfaced in a flea market just pissed me off something fierce. I've probably ignored that flea market, passed it right by. Now I'm wracked with guilt and if I had a second to spare, I'd stop. I swear!"

As in life, so too in 78 collecting.

Party Like It's 1899

Charley Patton

General consensus among blues scholars places Patton at the head of the great Mississippi Delta bluesmen that were first captured on disc. His gravelly voice is often hard to discern, but his guitar playing contains virtually all the moves that built every career from Robert Johnson on. Best heard on: Screamin' And Hollerin' The Blues (Revenant, 2003)

Skip James

His "Hard Time Killing Floor Blues" was revived for O Brother Where Art Thou? and brought some long-overdue recognition. Still, James's lone 1931 session remains one of the definitive events in blues history. His aching vocals and intricate guitar playing are unique among other Delta figures, a fact that only continues to increase his stature. Best heard on: The Complete Early Recordings (Yazoo, 1995)

Geeshie Wiley

Only given wide exposure recently through the Crumb soundtrack, Wiley's "Last Kind Word Blues" easily stands alongside any Delta blues masterpiece. Of her other known songs, "Skinny Leg Blues" is equally chilling for the immortal line, "I'm gonna cut your throat baby, and look down in your face," delivered with an audible wicked grin. Best heard on: American Primitive Vol II (Revenant, 2005)

Charlie Poole

Often hailed as the link between string bands and modern bluegrass, new facts about Poole's short life also show him to be the prototype hard living country outlaw. Who knows what he could have achieved if the Great Depression hadn't halted his career, but chances are someone or something would have killed him eventually. Best heard on: You Ain't Talkin' To Me (Sony Legacy, 2005)

Emmett Miller

His "trick voice" yodelling inspired Jimmie Rodgers, Hank Williams and Merle Haggard, but Miller's chosen path was as a blackface entertainer, a path that led only to obscurity. If you can ignore the racist overtones, the music remains as haunting as ever, courtesy of some of the greatest jazz players of the era. Best heard on: The Minstrel Man From Georgia (Sony Legacy, 1996)

Dock Boggs

A major rediscovery with the simultaneous reissue of the Harry Smith box and Greil Marcus' in-depth examination of his life in Invisible Republic, Boggs is now an iconic figure in old time music. His heavy banjo flailing and growling vocals are to country what Charley Patton's style is to blues, and his versions of "Sugar Baby" and "Pretty Polly" remain unsurpassed. Best heard on: Country Blues (Revenant, 1997)

The zealousness I experienced at that moment has been shared among 78 collectors since the 1950s when the recording industry switched from pressing records on shellac a valuable commodity during the Second World War to vinyl, a more durable and practical surface for the emerging LP and 45 markets. This commercial sea change also brought about a change in music itself; new, progressive forms, like rock'n'roll and cool jazz caught the public's imagination, replacing the archaic sounds most associated with the 78 era. The music industry embraced new technology, almost immediately leaving the historical preservation of the 78 legacy to collectors. While the 78 itself may be virtually extinct today, those who have preserved what copies do exist have continually seen their efforts pay off through the influence that some neglected artists have had on contemporary music.

There's no better example than Mississippi Delta bluesman Robert Johnson; the 29 sides recorded during his brief lifetime became prized by collectors for their musical quality. Through the efforts of independent collectors, Robert Johnson became a legendary influence on early rock'n'roll; his place in the pantheon was assured with the CD release of a pristine-sounding 1990 box set that collected his entire recorded output. For most collectors, it was the point at which he ceased to be a ghost and they moved on to more pressing mysteries that needed to be solved.

Jack White clearly has a thing for ghosts; references to them are peppered throughout the White Stripes' catalogue. He has done his part in keeping the ghosts alive by covering songs by Son House and Blind Willie McTell, artists that, by all rights, should have no connection to a middle-class kid who grew up in Detroit in the 1980s. But for more and more people like White, this land of ghosts the "old, weird America," as critic Greil Marcus put it is far more real than any music currently being made.

Most master recordings from this period have been lost, neglected or destroyed; it has been left to the self-styled musical archaeologists to scour attics, basements, and warehouses for more pieces to this never-ending puzzle. In many cases, this has led to collectors starting their own reissue labels, creating a separate industry and in some ways, an alternate history. Robert Johnson's more rough-edged predecessors of the 1920s are now most blues collectors' ultimate goal. The same goes for country music Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family no longer hold the same allure as the more "authentic" musicians who emerged from the backwoods of Tennessee and Virginia at a time when companies would record anyone who could bang out a tune on a banjo or fiddle.

Much of this critical shift has been helped along through the personal tastes of such high-profile figures as White, Bob Dylan and artist Robert Crumb. Crumb especially has had a profound influence since the acclaimed 1994 documentary about his life fully illuminated his obsession with 78 collecting and old time music's ongoing hold on his psyche. In fact, the best introduction to the music is still Crumb's series of blues and country "trading cards" that provide bios of his favourite artists.

The current revival in old time music can in many ways be traced to the reissue of Harry Smith's Anthology Of American Folk Music by Smithsonian/Folkways in 1997. Smith is the patron saint of 78 collectors, having had the vision to gather as many sides as he could during WWII before the shellac could be melted down. But Smith's real genius was to sift through those hundreds of old blues and country records and construct a personal-yet-unifying glimpse of an already bygone era.

When the Anthology first appeared in 1952, it was a cultural dividing line, spawning a new generation of artists Dylan among them whose styles were almost solely based around the music Smith had single-handedly preserved. Since its reappearance, the Anthology has accomplished this feat again in the alt-country world. The recent stripped-down, spooky efforts by The Be Good Tanyas, Neko Case, Elliott Brood, and even Tom Waits, owe much to the subversive spell that the Anthology has once again cast.

"The Anthology was a huge touchstone," says Dean Blackwood of Revenant Records, the current leader in old time reissues. "It was Harry's approach his fundamental irreverence, his distrust of institutions and academics, his impishness, and his relentless intellectual and creative honesty that was equally if not more important to us in terms of setting a course for Revenant." The label's latest release is American Primitive Vol. II, a stunning collection of rare pre-war folk, some of which has long been prized by aficionados, such as Geeshie Wiley's "Last Kind Word Blues," and relatively new discoveries such as the NuGrape Twins, gospel singer Homer Quincy Smith, and female prisoner Mattie May Thomas. Blackwood founded Revenant with the late, celebrated guitarist John Fahey, whose passion for all forms of "raw musics" led to genre-crossing collections by the likes of Captain Beefheart, Albert Ayler and rockabilly pioneer Charlie Feathers. "Almost all the recordings were items that Fahey had shared with me at one time or another," Blackwood says. "Sometimes he planted a clue that I had to follow up on later in some cases, after his death such as a brief mention of the recordings from the sewing room of Parchman Farm [Prison] where Mattie May Thomas sang her special, baleful songs. I think it was just an offhand comment about how he loved Geeshie and Elvie [Thomas] above all other female blues singers, with the possible exception of Mattie May. That kind of thing can get the juices flowing; you can't get your hands on those recordings quickly enough."

Blackwood's involvement with the label is rooted in a childhood fetish for 78s, which grew during the early 90s while he was working at Sub Pop's East coast office and attending Harvard law school. "I always had an obsession with 78s since being introduced to them as a kid at my great grandparents' house in Lawson, Arkansas," he says. "By 1995 I had finished law school and was working at a law firm in Nashville, and on the heels of a 78 project with Fahey I began to manage' him and help him with various legal and non-legal things. He came into a small inheritance that year and, instead of investing it wisely, opted for us to start a new record label venture."

Even for a latecomer to the 78 scene such as myself, it's easy to share the distrust of institutions and academics that Blackwood speaks of. The personal obsessions of hardcore collectors have led to strong arguments that jazz was dead by 1933, the last great blues singer was Howlin' Wolf, and country went to the great beyond with Hank Williams. Although he is internationally known in rock circles, Jeff Healey is part of this crowd. His collection of 78s is estimated at 25,000, and his love of early jazz prompted the formation of his other band, the Jazz Wizards, in which he plays trumpet; he also hosts his own old-time radio program. With such a vast stock of records, it's not surprising that Healey also got the bug at an early age. "It started off with records in my family, mostly ones that my grandmother played me when I was young," he says. "By the time I was 11, I had about 500 records, from semi-classical and war tunes, to dance bands and country."

As Healey's tastes became more refined, it only increased his desire to find more of what he liked. "The moment that my dad first gave me records that he got from a second-hand store, I had my coat on wanting to go back and get more. From that point on, we went anywhere to find records."

My own fetish manifested itself when I set out to find a gramophone. On looks alone, they are beautiful art-deco relics worth owning; the oversized horn that provides amplification accentuates a room like a giant orchid. I knew it wouldn't be easy, so when an ad for two at reasonable prices appeared, it seemed like serendipity. One gramophone was a gorgeous, full-size living room model that proved too much for my needs. I opted for a more portable one that I could picture being taken out for Gatsby-esque picnics by white-linen-clad couples topped with straw hats and parasols. The seller explained the simple mechanism, with its turntable that required hand cranking like the engine of a Model T Ford, and emphasising that the needle must be changed with each record. This sounded excessive until I examined the needle, which appeared only slightly more durable than a sharp pencil.

Getting the gramophone was a major score, but I really wanted records. I haggled until he threw in a few of his own, one of which I broke as soon as I got home the reason vinyl was invented was precisely because shellac 78s are so fragile. One I managed to hold onto was a version of Kurt Weill's "September Song," sung by some kid named Sinatra in 1946. Then I played "At Dawning," and it was just as strangely moving as I had hoped a window into an innocent past, with the tinny sound only adding to the overall disconcerting effect. As audiophiles have asserted since the rise of compact discs, part of the lasting appeal of records lies in a subconscious love of hearing those cracks and pops.

By his late teens, Healey was being asked to donate records to reissue projects, which suddenly made him quality-conscious. "Being asked to participate is exciting, but the challenge becomes finding the highest-quality recording. In many cases, the major labels have access to the original metal masters, but they aren't able to do the necessary clean-up work properly. I find that if the restoration isn't done by a musician, or someone who at least knows the music well, then the original sound quality is always compromised."

Blackwood has similar concerns whenever a new Revenant release is being prepared, a process that lasts two or three years. "There is certainly software available to get rid of static, but this will come at the expense of the high frequency end of the music, so you end up with something that sounds like it's playing behind a closed door down the hall. You lose all those sparkling highs. When in doubt, leave it alone. More noise generally also means more music."

Digitalisation has undeniably reached a point where sound can be extracted from any source. The McGill Audio Preservation Project (MAPP) in Montreal is one example of science aiding in the process. Catherine Lai, a PhD student with the Project, agrees that the intrinsic aspects of the music must come first. "As organisations and institutions convert musical material into digital formats, the need for efficient workflow management tools will increase because the digitization process is time-consuming, expensive and requires much human intervention," she says. "For example, the British Library holds over 2.5 million sound recordings. Even with a conservative estimate of digitisation time at 30 minutes per recording, the total digitisation time required would be at least 1.25 million hours, or 142 years."

While Lai says that much of the research has involved determining the best analog-to-digital conversion system, MAPP's major contribution could be its use of optical scans. "There are tremendous advantages to preserving phonograph recordings as 2D or 3D images. Without touching the recordings themselves, which deteriorate upon playback, we can experiment freely with methods of converting audio to determine the best method."

On the night of this year's Mardi Gras, there was an unusual record release party at Toronto's Cameron House. On sale for $25 was a brand new 78 rpm recording by Miss Alex Pangman and Colonel Tom Parker of the Backstabbers, called "Dead Drunk Blues," with the proceeds going to Habitat For Humanity's New Orleans Musicians Village Project. "We're unapologetic in our love of these discs; we have about 2,000 between the two of us," Parker says. "I wrote the song last March, and after the devastation of Katrina, decided that we needed to help the city however we could."

The Katrina disaster recalled both the last great New Orleans flood, in 1927, and the original songs that chronicled it: Blind Lemon Jefferson's "Rising High Water Blues"; Memphis Minnie's "When The Levee Breaks"; Charley Patton's "High Water Everywhere." The ghosts continue to haunt us, as they do Dean Blackwood. "The idea that somehow this stuff is solely the province of those with the divine seal on their forehead, that one may therefore elevate one's own mission by impugning as impure the motives of others who may traffic in similar material, is a notion I don't share with certain other folks who fancy themselves the keepers of the flame. I do believe you have an obligation to do right by the work to bring to it an excellence of scholarship, sonics, and careful selection."

If you've ever purchased a compilation of old time blues or country, chances are some of it has come from the collection of Joe Bussard. His thorough work in finding rare 78s throughout rural areas in the Southeastern U.S. has made him the source of best-known-quality recordings for many reissues, including Revenant's Charley Patton box set, Screamin' And Hollerin' The Blues, and the restored Smith Anthology. Yet, he is also known for making tapes for anyone looking for a song that, more often than not, only he possesses. In a 1998 profile on Bussard for The Washington City Paper, the head of noted blues and folk reissue label Yazoo/Shanachie Richard Nevins stated, "The important thing about Joe Bussard is that he has disseminated the music more than anybody else on earth. He has preserved and popularised the music more than anyone, and he's done more for the music than anyone. All the institutions are bogus nonsense. They don't do any good at all."

Bussard built the bulk of his collection in the '50s and '60s, often going door-to-door to follow leads. His findings made him the envy of other collectors, including John Fahey, who became a close friend. Bussard was eventually compelled to start his own exclusively 78 label, Fonotone, which released Fahey's first recordings, Bussard's own group, Jolly Joe's Jug Band, and many others. A new box set from the Dust-To-Digital label tells the complete Fonotone story and gives Bussard his rightful due as the last pure old time music entrepreneur. Still, as long as his old time collection remains intact, those wishing to dip into it as Sony also did for last year's remarkable Charlie Poole box set, You Ain't Talkin' To Me will keep coming to him. "I'm not giving [my collection] to any of those [labels]," Bussard said in 98. "If you give it to them, they shove it back in some hole, and there it sits. It ain't no worry of mine. I don't expect to kick off that quick. I expect to be around another 20 years to enjoy it."

My first serious quest to expand my collection forced me back to the classifieds in search of anyone selling anything. One ad eventually appeared proclaiming "jazz and country 78s for sale." It was clearly a direct personal plea, and I got the guy on the phone right away. But he seemed a little hesitant, wanting to meet me in the parking lot of a nearby Tim Horton's. I made sure to arrive early, and recognised my man the moment a well-driven 70s land shark pulled up to the front window. As I made eye contact with the twitchy older fellow, he wasn't eager to come in for coffee, so I went out and introduced myself. He didn't waste time getting down to business, pulling stacks of 78s out of his back seat, and showing me more in the trunk. I could only guess what people passing us must have been thinking, as I tried to digest his detailed descriptions of each record while making my picks. Sensing I was in over my head, I ended up giving him $50 for as many records as I could carry several Hank Snow and Roy Acuff sides among them and we both went away happy. I've since seen him on other occasions peddling his wares at used record stores around town. He never remembers me.

After that initial success, it's been hard to find 78s of real quality, but the need to dig will never go away. Even for long-time collectors, there are things yet to be found. But as Blackwood admits, nowadays this is largely left up to fate. "I'm amazed every time something surfaces, to tell you the truth," he says. "The recent Blind Joe Reynolds record that surfaced in a flea market just pissed me off something fierce. I've probably ignored that flea market, passed it right by. Now I'm wracked with guilt and if I had a second to spare, I'd stop. I swear!"

As in life, so too in 78 collecting.

Party Like It's 1899

Charley Patton

General consensus among blues scholars places Patton at the head of the great Mississippi Delta bluesmen that were first captured on disc. His gravelly voice is often hard to discern, but his guitar playing contains virtually all the moves that built every career from Robert Johnson on. Best heard on: Screamin' And Hollerin' The Blues (Revenant, 2003)

Skip James

His "Hard Time Killing Floor Blues" was revived for O Brother Where Art Thou? and brought some long-overdue recognition. Still, James's lone 1931 session remains one of the definitive events in blues history. His aching vocals and intricate guitar playing are unique among other Delta figures, a fact that only continues to increase his stature. Best heard on: The Complete Early Recordings (Yazoo, 1995)

Geeshie Wiley

Only given wide exposure recently through the Crumb soundtrack, Wiley's "Last Kind Word Blues" easily stands alongside any Delta blues masterpiece. Of her other known songs, "Skinny Leg Blues" is equally chilling for the immortal line, "I'm gonna cut your throat baby, and look down in your face," delivered with an audible wicked grin. Best heard on: American Primitive Vol II (Revenant, 2005)

Charlie Poole

Often hailed as the link between string bands and modern bluegrass, new facts about Poole's short life also show him to be the prototype hard living country outlaw. Who knows what he could have achieved if the Great Depression hadn't halted his career, but chances are someone or something would have killed him eventually. Best heard on: You Ain't Talkin' To Me (Sony Legacy, 2005)

Emmett Miller

His "trick voice" yodelling inspired Jimmie Rodgers, Hank Williams and Merle Haggard, but Miller's chosen path was as a blackface entertainer, a path that led only to obscurity. If you can ignore the racist overtones, the music remains as haunting as ever, courtesy of some of the greatest jazz players of the era. Best heard on: The Minstrel Man From Georgia (Sony Legacy, 1996)

Dock Boggs

A major rediscovery with the simultaneous reissue of the Harry Smith box and Greil Marcus' in-depth examination of his life in Invisible Republic, Boggs is now an iconic figure in old time music. His heavy banjo flailing and growling vocals are to country what Charley Patton's style is to blues, and his versions of "Sugar Baby" and "Pretty Polly" remain unsurpassed. Best heard on: Country Blues (Revenant, 1997)