"Why do you dislike rock'n'roll so much?" "It's dead. It's a disease. It's a plague. It's been going on for too long. It's history. It's vile. It's not achieving anything, it's just regression."

John Lydon (Public Image Limited), to Tom Snyder of The Tomorrow Show, June 1980

"...The river moves on. Today punk is dead, the avant-garde has emerged as a powerful force, and disco is considered to be the music of the people."

From "Dialectics Meets Disco," a Melody Maker article about Gang of Four, May 1979

At the close of the 1970s, the North American masses had more or less exhausted their love affair with disco. Saturday Night Fever had brought the formerly underground club phenomenon crashing into the mainstream in 1977, overthrowing rock from its long-held throne. But a suspicion had begun to creep into the collective consciousness: that disco was all surface but no substance; it didn't represent the true experiences of everyday life in the way that rock usually had; it was the soundtrack of homosexual deviants and the vacuous rich. The time had come to reclaim "proper" music that is, the likes Aerosmith and Journey to its rightful place atop the charts.

When Chicago disc jockey Steve Dahl organised a mass, ceremonial burning of disco records in July, 1979, at the city's Comiskey Park stadium enthusiastically attended by thousands it was thought to be the final, irrefutable signifier that disco was dead. And, commercially, it soon was. Meanwhile, in Britain, acclaimed, cutting-edge bands such as Gang of Four, Public Image Limited (PiL), and A Certain Ratio, who had been galvanised by punk's do-it-yourself impulse, were incorporating disco's nimble rhythms, fluid bass lines, and funk-inspired guitars into their music. It was, to say the least, an unlikely marriage. Punk was largely created in retaliation against the bourgeois decadence that had been slowly infiltrating rock music a decadence that disco wielded like a point of pride. How could this happen? Furthermore, why do the results still sound so revolutionary today? More than 20 years after the fact, no one may be any closer to unravelling the entire circumstances that created the musical alchemy known as "post-punk." But it has recently become the subject of substantial reappraisal, not only by the music press, but also a new generation of artists. Compilation albums of original post-punk like In the Beginning There Was Rhythm, Disco Not Disco, and Anti NY are pricking up jaded ears, and bands including Radio 4, the Rapture, Life Without Buildings, and Erase Errata are creating music that hearkens back to the post-punk era while embellishing it with contemporary touches. Unlike, say, Britpop, however, an attitude prevails that this is less a nostalgic retreat than the reopening of an investigation into music that was abandoned before its potential was fully realised.

For Simon Reynolds to be involved, it would have to be. The New York-based British journalist is distinctive for having always been defiantly anti-retro. Rave culture was the focus of most of his writing throughout the '90s, and he has been a vocal critic of what he perceives to be rampant conservatism in contemporary British guitar pop. But in the December issue of British monthly Uncut, he delivered an authoritative essay about post-punk, which was followed by news that he's writing a book about the subject for a planned 2003 release. "It was as though punk had bequeathed a tremendous sense of responsibility almost a burden because music now had a renewed sense of mission and a sense (delusion?) that it had the power to change things, so where you went next with that energy was very important," he says of the post-punk era. "It was so bound up in the future, the project of making 80s music [the press] started talking about 80s pop' as early as 1978, as a kind of duty So I'm interested in the post-punk period as both a lost future, and a period of lost futurism."

"The pairing of punk and disco was indeed a curious one," says Sean P., a London-based DJ who helped compile Disco Not Disco volumes one and two. "Though something that the musics had in common was energy albeit on different levels and in their own way both stood for lifestyles and ideals that opposed the norm. Punk dealt more with gritty realities by facing them head-on; disco would avoid the issues a lot of the time by simply blotting out everyday routine. It was about dancing, having fun, escapism."

Post-punk occupied an intriguing middle ground between these two poles. Many young musicians felt that punk's progressive ideologies weren't reflected in punk rock itself, which was little more than a scrappier variation on traditional hard rock. In disco and in funk, avant-jazz, and dub reggae, among others lay sonic possibilities that were infinitely more malleable and exciting. "Certain influential music writers in the UK noticed the fact that real working-class people' weren't into punk they were down at the disco," notes Reynolds.

The Punks Dance

Many of the best post-punk records provided the visceral and physical satisfactions of dance music, but subverted its conventions with the subtle air of foreboding and socio-political lyrics that was common to punk. Entertainment!, the 1980 debut album by Gang of Four, was one of these. Sparse, linear, and saturated with an anger constantly held back from boiling point, it was like funk in a straitjacket. Tracks such as "Natural's Not in It" and "I Found That Essence Rare" criticised the apathy of modern consumer culture, yet whether these thoughts infiltrated the hordes dancing to them at night clubs is a matter of debate. Typical of the delicate relationship between post-punk's medium and message, Gang bassist Dave Allen quit the group little over a year after the album's release, citing, among other reasons, that singer Jon King's politics were becoming "wet" and "liberal."

Like Entertainment!, many of the post-punk era's key long-players proved to be one-offs, as musicians' competing musical and ideological visions split bands apart prematurely. PiL's Metal Box (released in North America as Second Edition) a claustrophobic melange of cavernous dub rhythms and John Lydon's anguished howl was the collective's lone masterpiece before PiL became an anonymous vehicle for Lydon's increasingly uninspired whims. Not untypical was a case like the Pop Group, who peaked with one single (the classic punk-funk scorcher "She Is Beyond Good and Evil") before the untenable weight of the group's moral agenda more or less reduced music to a secondary concern. "How much does the Pop Group indulge in confusion of its music at the expense of controlling it?" asked a review of their 1979 debut album, Y.

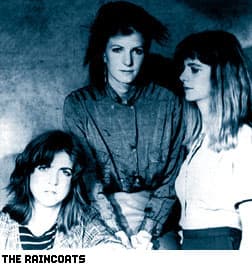

Bands who remained together long enough to acquire technical abilities that were in league with their goals often achieved brilliance. The Raincoats were four women from London whose music grew in dazzlingly confident leaps across three albums from 1979 to 1984. By the time of their parting shot, Moving, they sounded like no other group, addressing themes of female self-possession without sloganeering or using the male-identified structures that were part and parcel of rock. This was dance music designed upon the unconventional rhythms of a mind engaged in fevered thought. If "Animal Rhapsody" had been released by a label experienced in servicing dance clubs, it could have been a floor-filler.

"We did not have an agenda to want to sell records," recalls bassist Gina Birch. "We were just interested in exploring possibilities, trying out tunes on any instrument and stumbling around until there was a coexistence of sounds that worked for us."

The Raincoats' lack of careerism was typical of many post-punk groups, who would break up amicably after only two or three records because they felt they had achieved their mission. This, too, played a large part in the movement's short life span.

America's Disco Underground

In North America, the aftermath of disco's fall from favour produced a different result. Rather than disco being absorbed into punk, the opposite was more often the case. Especially in New York City, the most recognised of the culture's hotbeds, disco simply returned to the underground from which it originated. Upon its descent, it also met up with the emerging hip-hop culture, becoming a multi-faceted beast whose effects are still being felt in modern day R&B productions. Disco Not Disco and Anti NY offer examples of the music that could be heard in clubs like Paradise Garage long after Studio 54 had shuttered its doors. In rare instances, commercially successful groups seized upon this sound and took it into the charts: Talking Heads' brilliant Remain in Light and the Clash's uneven but unfairly maligned Sandinista! are prime examples.

Arguably the most interesting of New York's post-punk-identified acts was ESG, made up of four sisters from the South Bronx Deborah, Marie, Renee and Valerie Scroggins who were encouraged to take up music by their mother to help keep them off the rough city streets. Huge fans of James Brown, they produced hypnotic, almost creepy grooves that unknowingly echoed the punk-funk hybrids of British groups like A Certain Ratio and PiL. "Our sound was and always will be our own," says Renee. "We had no idea about the music we were being compared with. We have always thought of ourselves as a funk-dance band."

An unusual chain of circumstances led to ESG becoming the opening act for A Certain Ratio when they came to New York in '81 to record their debut album with Factory Records' unofficial in-house producer Martin Hannett. The visiting Manchester group offered ESG their remaining studio time, and the three tracks they laid down in a single day "Moody," "You're No Good" and "UFO" were released by Factory later that year. A bewitching meeting of austere European cool and percolating urban funk, the tracks have been sampled countless times by hip-hop artists including Public Enemy and LL Cool J. The 2000 anthology A South Bronx Story gave the still-active ESG an unprecedented profile, and a new generation of fans (hear C O C O's recent self-titled debut on K Records for proof). Dance music had advanced immeasurably since the early '80s, but ESG were far enough removed from everything that surrounded them that they still sound eerily contemporary two decades later a quality they share in common with scores of post-punk-era artists.

"I think that most musicians doing anything interesting seek out things that are different and exciting, from wherever they can find them," says Matt Safer, bassist for New York-transplanted trio, the Rapture. On their most recent record, the Out of the Races and Onto the Tracks EP, the band's taut, stop-start rhythms and abrasive textures evidence a certain debt to Gang of Four, Wire, and the Pop Group. But rather than simply borrow post-punk's surface traits without adhering to its policy of musical progression, the Rapture also look to contemporary dance records, as well as avant-punk structures that suggest admiration for Fugazi (best exemplified by their twelve-inch single "House of Jealous Lovers"). "We were all attracted to post-punk because of our interests in dance music and in rhythm," Safer continues. "The post-punk movement was certainly inspired by, and went on to inspire, a lot of really creative things." Equally exciting are Brooklyn's Radio 4 (named after the final track on Metal Box), whose new album Gotham! also goes some way toward finding common ground between the rock club and the dance-floor. Meant to serve as an aural snapshot of modern life in New York, its relentless energy and occasionally disorienting collision of sounds achieve that goal wonderfully. Explains bassist Anthony Roman: "There's a club we were going to while writing this record where they had a rock room and they would play all new wave, post-punk, et cetera; and there was another room where they would play great house stuff with live percussion accompanying it. We used to stand in the doorway that connected the two rooms and say, This is what the record should sound like.'"

Radio 4, too, have reconfigured their music for the DJ, offering an extended mix of the incendiary 2001 track "Dance to the Underground" on twelve-inch single. Both Radio 4 and the Rapture have, on their latest records, worked with NYC production team, the DFA. Made up of Tim Goldsworthy and James Murphy, the pair bring their respective backgrounds in dance (UNKLE, David Holmes) and rock (Trans Am, Six Finger Satellite) to the studio in order to, says Safer, "help blur that distinction a bit."

Perhaps it was inevitable that a future generation of guitar bands would discover and take inspiration from post-punk. The not unreasonable but entirely derivative charms of the Strokes, the Hives, the Vines, et al, seemingly imply that rock experienced its peak years decades! ago, and all that can be done now is to fan the embers of its once-mighty flame. Like disco in its heyday, today's proponents of rock culture like to dismiss R&B as synthetic and soulless, but there is more evidence of rock's maverick spirit, of its original mission to disrupt and displace, in the latest Missy Elliot or Dr. Dre production than in the whole of the Strokes' Is This It. Bands who have adopted post-punk's investigative spirit, who use the full palette of musical colours available to them, are the ones that will create a future worth hearing. "I think very few bands of any quality could really be distilled down to one influence or one interest," says Safer. "It's a number of things, musical and otherwise, that get thrown in, and the music that results from it is just trying to make sense of that."

This way forward.

Chic

Winning the War

During the late '70s, Chic were second only to the Bee Gees in terms of being inextricably associated with disco. The New York-based mixed-gender quintet had, by 1979, become the best-selling singles act in the history of Atlantic Records; dance-floor fillers including "Dance, Dance, Dance," "Le Freak" and "Good Times" sold millions of copies in a matter of weeks.

Yet Chic, like most disco artists at the time, were afforded little respect by a North American music press that invariably associated credibility with rock. Musicians may have begrudgingly acknowledged that songwriters and group masterminds Nile Rodgers (guitar) and Bernard Edwards (bass) were exemplary players, and possessed of a seemingly preternatural ability to produce instant worldwide number one records. But Chic's music, wisdom prevailed, was a shallow victory - financial, not artistic. In Europe, however, and especially in Britain, Chic were demigods. Rodgers and Edwards were frequently interviewed by the weekly music press there, who deemed the pair modern-day equivalents of Lennon & McCartney or Bacharach & David songwriters whose enormous popularity was due reward for talent that simply couldn't be denied. And Chic, British writers never tired of stressing, had become a touchstone for virtually every British post-punk group that mattered. "In musical terms, the innovative' new wave bands from Public Image Limited to Gang of Four freely borrow from disco while disco acts don't, and have no need to, return the compliment," read a 1979 Melody Maker piece.

"If you had any idea how many fights I had to break up between punk rock bands wanting to kick the shit out of American rock bands who were coming off as anti-Chic," laughs Rodgers, speaking in late May from a Connecticut recording studio. "It was really amazing how the British bands would almost feel like they had to protect us. Groups like the Clash, they thought that we were the coolest thing in the world, and how could people not get the essence of what we were doing?" Bow Wow Wow and Gang of Four were also vocal supporters of Chic; the latter had wanted Rodgers to produce them, but they settled on being drinking partners instead.

"The English movers and shakers were basically working-class type of people who were struggling to get up," Rodgers explains. "You think about some of the great British pop superstars: you look at Sting coming from Newcastle, Bryan Ferry comes from Newcastle, the Beatles come from Liverpool. These are working-class people. It's being raised in a system that says there are people that society deems better than you simply by their birthright. So a person like that would absolutely be much more in tune with the philosophy of a group like Chic, would understand that we were trying to reach for the stars. As a matter of fact, that's even the lyrics in one of our songs, My Feet Keep Dancing': Reach for the stars fly into space, or maybe save the human race.' It was all of these very, very highfalutin concepts that were achievable in our minds if you were optimistic."

Rodgers also stresses that disco was an explicitly political culture, although it was rarely recognised as such. "Disco being the music that happened after the political '60s, [it] was a celebration of accomplishment. We felt like we ended the Vietnam war, through protesting, getting killed, Kent State this was our crowning achievement. Therefore, we also liberated gay people, started the women's movement, all of that stuff. And now, just like when prohibition ended, we started celebrating. And that's what Chic was all about."

When Chic completed a triple-bill with the Clash and Blondie for a series of gigs at defunct New York club Bond's in 1981, with local B-boys invading the stage for an all-inclusive encore of "Rock the Casbah," the perceived barriers between rock and dance music became non-existent. "It was amazing," Rodgers recalls. "It was the essence of disco and punk together as a unified force, and it was just one of those kind of things that came and went. But we didn't think about it as history it's just what we do."

Various

In the Beginning There Was Rhythm (Soul Jazz, 2002)

Likely the best single-disc primer of the post-punk era, and perhaps the only place to find essential tracks like the Pop Group's "She is Beyond Good and Evil" and the Slits' "In the Beginning " without risking personal bankruptcy at the hands of eBay.

Gang of Four

Entertainment! (Warner, 1980)

For all of its frankly humourless dogma about society's moral collapse, this is a guitar record that, like Television's Marquee Moon, you can feel in your spine.

The Raincoats

Moving (Rough Trade, 1984; Geffen, 1993 out of print)

Alongside the Slits, this London group exemplified how punk allowed women to produce music that was truly their own. Moving remains one of the best examples of post-punk's cross-pollinating impulse, with "Animal Rhapsody" a dazzling declaration of female self-will set to an irresistible disco beat.

Radio 4

Gotham! (Gern Blandsten, 2002)

Two arguments in favour of the validity of guitar rock in 2002, keeping one eye on the distortion pedal and the other on the dance floor. These New York groups take up post-punk's challenge to find new ways of making the familiar unfamiliar and succeed brilliantly.

ESG

A South Bronx Story (Soul Jazz, 2000)

An incomparable sound that could only have happened by accident. Sweltering NYC funk set adrift in outer space, or left to fend for itself on the cold, grey streets of Manchester.

Delta 5

See the Whirl (Pre, 1981 out of print)

This Leeds, UK quintet leapt from their comparatively crude early singles on Rough Trade to this remarkably assured debut and, it transpired, only album. Angular and terse but also melodic and graceful (including horn arrangements and pedal steel). Someone reissue this now!

Talking Heads

Remain in Light (Sire, 1980)

Talking Heads were one of the few American rock bands enlightened and open-minded enough to absorb the influences of disco, funk, and world music in the early '80s. Produced by Brian Eno, it still sounds futuristic today, and was savvy enough in its blending of the experimental and the accessible to have been a Top 40 album.

Josef K

Young and Stupid (LTM, 2002)

Punk rock possessed of a romantic heart. This Scottish group sounded anxious and suspicious but ultimately, like idealists. "The Missionary" and "Sorry for Laughing" are dance songs for caffeine addicts a summit meeting between Captain Beefheart and Chic.

Various

Disco Not Disco (Strut, 2000)

Post-punk artists admired the oft-overlooked experimentalism of early disco (Giorgio Moroder's Donna Summer productions, for instance). When mainstream disco "died," it gained a new life in the underground, where it rediscovered its spirit of adventure. Early '80s tracks featured here by Yoko Ono, Common Sense, and Ian Dury engage the brain and the booty.

John Lydon (Public Image Limited), to Tom Snyder of The Tomorrow Show, June 1980

"...The river moves on. Today punk is dead, the avant-garde has emerged as a powerful force, and disco is considered to be the music of the people."

From "Dialectics Meets Disco," a Melody Maker article about Gang of Four, May 1979

At the close of the 1970s, the North American masses had more or less exhausted their love affair with disco. Saturday Night Fever had brought the formerly underground club phenomenon crashing into the mainstream in 1977, overthrowing rock from its long-held throne. But a suspicion had begun to creep into the collective consciousness: that disco was all surface but no substance; it didn't represent the true experiences of everyday life in the way that rock usually had; it was the soundtrack of homosexual deviants and the vacuous rich. The time had come to reclaim "proper" music that is, the likes Aerosmith and Journey to its rightful place atop the charts.

When Chicago disc jockey Steve Dahl organised a mass, ceremonial burning of disco records in July, 1979, at the city's Comiskey Park stadium enthusiastically attended by thousands it was thought to be the final, irrefutable signifier that disco was dead. And, commercially, it soon was. Meanwhile, in Britain, acclaimed, cutting-edge bands such as Gang of Four, Public Image Limited (PiL), and A Certain Ratio, who had been galvanised by punk's do-it-yourself impulse, were incorporating disco's nimble rhythms, fluid bass lines, and funk-inspired guitars into their music. It was, to say the least, an unlikely marriage. Punk was largely created in retaliation against the bourgeois decadence that had been slowly infiltrating rock music a decadence that disco wielded like a point of pride. How could this happen? Furthermore, why do the results still sound so revolutionary today? More than 20 years after the fact, no one may be any closer to unravelling the entire circumstances that created the musical alchemy known as "post-punk." But it has recently become the subject of substantial reappraisal, not only by the music press, but also a new generation of artists. Compilation albums of original post-punk like In the Beginning There Was Rhythm, Disco Not Disco, and Anti NY are pricking up jaded ears, and bands including Radio 4, the Rapture, Life Without Buildings, and Erase Errata are creating music that hearkens back to the post-punk era while embellishing it with contemporary touches. Unlike, say, Britpop, however, an attitude prevails that this is less a nostalgic retreat than the reopening of an investigation into music that was abandoned before its potential was fully realised.

For Simon Reynolds to be involved, it would have to be. The New York-based British journalist is distinctive for having always been defiantly anti-retro. Rave culture was the focus of most of his writing throughout the '90s, and he has been a vocal critic of what he perceives to be rampant conservatism in contemporary British guitar pop. But in the December issue of British monthly Uncut, he delivered an authoritative essay about post-punk, which was followed by news that he's writing a book about the subject for a planned 2003 release. "It was as though punk had bequeathed a tremendous sense of responsibility almost a burden because music now had a renewed sense of mission and a sense (delusion?) that it had the power to change things, so where you went next with that energy was very important," he says of the post-punk era. "It was so bound up in the future, the project of making 80s music [the press] started talking about 80s pop' as early as 1978, as a kind of duty So I'm interested in the post-punk period as both a lost future, and a period of lost futurism."

"The pairing of punk and disco was indeed a curious one," says Sean P., a London-based DJ who helped compile Disco Not Disco volumes one and two. "Though something that the musics had in common was energy albeit on different levels and in their own way both stood for lifestyles and ideals that opposed the norm. Punk dealt more with gritty realities by facing them head-on; disco would avoid the issues a lot of the time by simply blotting out everyday routine. It was about dancing, having fun, escapism."

Post-punk occupied an intriguing middle ground between these two poles. Many young musicians felt that punk's progressive ideologies weren't reflected in punk rock itself, which was little more than a scrappier variation on traditional hard rock. In disco and in funk, avant-jazz, and dub reggae, among others lay sonic possibilities that were infinitely more malleable and exciting. "Certain influential music writers in the UK noticed the fact that real working-class people' weren't into punk they were down at the disco," notes Reynolds.

The Punks Dance

Many of the best post-punk records provided the visceral and physical satisfactions of dance music, but subverted its conventions with the subtle air of foreboding and socio-political lyrics that was common to punk. Entertainment!, the 1980 debut album by Gang of Four, was one of these. Sparse, linear, and saturated with an anger constantly held back from boiling point, it was like funk in a straitjacket. Tracks such as "Natural's Not in It" and "I Found That Essence Rare" criticised the apathy of modern consumer culture, yet whether these thoughts infiltrated the hordes dancing to them at night clubs is a matter of debate. Typical of the delicate relationship between post-punk's medium and message, Gang bassist Dave Allen quit the group little over a year after the album's release, citing, among other reasons, that singer Jon King's politics were becoming "wet" and "liberal."

Like Entertainment!, many of the post-punk era's key long-players proved to be one-offs, as musicians' competing musical and ideological visions split bands apart prematurely. PiL's Metal Box (released in North America as Second Edition) a claustrophobic melange of cavernous dub rhythms and John Lydon's anguished howl was the collective's lone masterpiece before PiL became an anonymous vehicle for Lydon's increasingly uninspired whims. Not untypical was a case like the Pop Group, who peaked with one single (the classic punk-funk scorcher "She Is Beyond Good and Evil") before the untenable weight of the group's moral agenda more or less reduced music to a secondary concern. "How much does the Pop Group indulge in confusion of its music at the expense of controlling it?" asked a review of their 1979 debut album, Y.

Bands who remained together long enough to acquire technical abilities that were in league with their goals often achieved brilliance. The Raincoats were four women from London whose music grew in dazzlingly confident leaps across three albums from 1979 to 1984. By the time of their parting shot, Moving, they sounded like no other group, addressing themes of female self-possession without sloganeering or using the male-identified structures that were part and parcel of rock. This was dance music designed upon the unconventional rhythms of a mind engaged in fevered thought. If "Animal Rhapsody" had been released by a label experienced in servicing dance clubs, it could have been a floor-filler.

"We did not have an agenda to want to sell records," recalls bassist Gina Birch. "We were just interested in exploring possibilities, trying out tunes on any instrument and stumbling around until there was a coexistence of sounds that worked for us."

The Raincoats' lack of careerism was typical of many post-punk groups, who would break up amicably after only two or three records because they felt they had achieved their mission. This, too, played a large part in the movement's short life span.

America's Disco Underground

In North America, the aftermath of disco's fall from favour produced a different result. Rather than disco being absorbed into punk, the opposite was more often the case. Especially in New York City, the most recognised of the culture's hotbeds, disco simply returned to the underground from which it originated. Upon its descent, it also met up with the emerging hip-hop culture, becoming a multi-faceted beast whose effects are still being felt in modern day R&B productions. Disco Not Disco and Anti NY offer examples of the music that could be heard in clubs like Paradise Garage long after Studio 54 had shuttered its doors. In rare instances, commercially successful groups seized upon this sound and took it into the charts: Talking Heads' brilliant Remain in Light and the Clash's uneven but unfairly maligned Sandinista! are prime examples.

Arguably the most interesting of New York's post-punk-identified acts was ESG, made up of four sisters from the South Bronx Deborah, Marie, Renee and Valerie Scroggins who were encouraged to take up music by their mother to help keep them off the rough city streets. Huge fans of James Brown, they produced hypnotic, almost creepy grooves that unknowingly echoed the punk-funk hybrids of British groups like A Certain Ratio and PiL. "Our sound was and always will be our own," says Renee. "We had no idea about the music we were being compared with. We have always thought of ourselves as a funk-dance band."

An unusual chain of circumstances led to ESG becoming the opening act for A Certain Ratio when they came to New York in '81 to record their debut album with Factory Records' unofficial in-house producer Martin Hannett. The visiting Manchester group offered ESG their remaining studio time, and the three tracks they laid down in a single day "Moody," "You're No Good" and "UFO" were released by Factory later that year. A bewitching meeting of austere European cool and percolating urban funk, the tracks have been sampled countless times by hip-hop artists including Public Enemy and LL Cool J. The 2000 anthology A South Bronx Story gave the still-active ESG an unprecedented profile, and a new generation of fans (hear C O C O's recent self-titled debut on K Records for proof). Dance music had advanced immeasurably since the early '80s, but ESG were far enough removed from everything that surrounded them that they still sound eerily contemporary two decades later a quality they share in common with scores of post-punk-era artists.

"I think that most musicians doing anything interesting seek out things that are different and exciting, from wherever they can find them," says Matt Safer, bassist for New York-transplanted trio, the Rapture. On their most recent record, the Out of the Races and Onto the Tracks EP, the band's taut, stop-start rhythms and abrasive textures evidence a certain debt to Gang of Four, Wire, and the Pop Group. But rather than simply borrow post-punk's surface traits without adhering to its policy of musical progression, the Rapture also look to contemporary dance records, as well as avant-punk structures that suggest admiration for Fugazi (best exemplified by their twelve-inch single "House of Jealous Lovers"). "We were all attracted to post-punk because of our interests in dance music and in rhythm," Safer continues. "The post-punk movement was certainly inspired by, and went on to inspire, a lot of really creative things." Equally exciting are Brooklyn's Radio 4 (named after the final track on Metal Box), whose new album Gotham! also goes some way toward finding common ground between the rock club and the dance-floor. Meant to serve as an aural snapshot of modern life in New York, its relentless energy and occasionally disorienting collision of sounds achieve that goal wonderfully. Explains bassist Anthony Roman: "There's a club we were going to while writing this record where they had a rock room and they would play all new wave, post-punk, et cetera; and there was another room where they would play great house stuff with live percussion accompanying it. We used to stand in the doorway that connected the two rooms and say, This is what the record should sound like.'"

Radio 4, too, have reconfigured their music for the DJ, offering an extended mix of the incendiary 2001 track "Dance to the Underground" on twelve-inch single. Both Radio 4 and the Rapture have, on their latest records, worked with NYC production team, the DFA. Made up of Tim Goldsworthy and James Murphy, the pair bring their respective backgrounds in dance (UNKLE, David Holmes) and rock (Trans Am, Six Finger Satellite) to the studio in order to, says Safer, "help blur that distinction a bit."

Perhaps it was inevitable that a future generation of guitar bands would discover and take inspiration from post-punk. The not unreasonable but entirely derivative charms of the Strokes, the Hives, the Vines, et al, seemingly imply that rock experienced its peak years decades! ago, and all that can be done now is to fan the embers of its once-mighty flame. Like disco in its heyday, today's proponents of rock culture like to dismiss R&B as synthetic and soulless, but there is more evidence of rock's maverick spirit, of its original mission to disrupt and displace, in the latest Missy Elliot or Dr. Dre production than in the whole of the Strokes' Is This It. Bands who have adopted post-punk's investigative spirit, who use the full palette of musical colours available to them, are the ones that will create a future worth hearing. "I think very few bands of any quality could really be distilled down to one influence or one interest," says Safer. "It's a number of things, musical and otherwise, that get thrown in, and the music that results from it is just trying to make sense of that."

This way forward.

Chic

Winning the War

During the late '70s, Chic were second only to the Bee Gees in terms of being inextricably associated with disco. The New York-based mixed-gender quintet had, by 1979, become the best-selling singles act in the history of Atlantic Records; dance-floor fillers including "Dance, Dance, Dance," "Le Freak" and "Good Times" sold millions of copies in a matter of weeks.

Yet Chic, like most disco artists at the time, were afforded little respect by a North American music press that invariably associated credibility with rock. Musicians may have begrudgingly acknowledged that songwriters and group masterminds Nile Rodgers (guitar) and Bernard Edwards (bass) were exemplary players, and possessed of a seemingly preternatural ability to produce instant worldwide number one records. But Chic's music, wisdom prevailed, was a shallow victory - financial, not artistic. In Europe, however, and especially in Britain, Chic were demigods. Rodgers and Edwards were frequently interviewed by the weekly music press there, who deemed the pair modern-day equivalents of Lennon & McCartney or Bacharach & David songwriters whose enormous popularity was due reward for talent that simply couldn't be denied. And Chic, British writers never tired of stressing, had become a touchstone for virtually every British post-punk group that mattered. "In musical terms, the innovative' new wave bands from Public Image Limited to Gang of Four freely borrow from disco while disco acts don't, and have no need to, return the compliment," read a 1979 Melody Maker piece.

"If you had any idea how many fights I had to break up between punk rock bands wanting to kick the shit out of American rock bands who were coming off as anti-Chic," laughs Rodgers, speaking in late May from a Connecticut recording studio. "It was really amazing how the British bands would almost feel like they had to protect us. Groups like the Clash, they thought that we were the coolest thing in the world, and how could people not get the essence of what we were doing?" Bow Wow Wow and Gang of Four were also vocal supporters of Chic; the latter had wanted Rodgers to produce them, but they settled on being drinking partners instead.

"The English movers and shakers were basically working-class type of people who were struggling to get up," Rodgers explains. "You think about some of the great British pop superstars: you look at Sting coming from Newcastle, Bryan Ferry comes from Newcastle, the Beatles come from Liverpool. These are working-class people. It's being raised in a system that says there are people that society deems better than you simply by their birthright. So a person like that would absolutely be much more in tune with the philosophy of a group like Chic, would understand that we were trying to reach for the stars. As a matter of fact, that's even the lyrics in one of our songs, My Feet Keep Dancing': Reach for the stars fly into space, or maybe save the human race.' It was all of these very, very highfalutin concepts that were achievable in our minds if you were optimistic."

Rodgers also stresses that disco was an explicitly political culture, although it was rarely recognised as such. "Disco being the music that happened after the political '60s, [it] was a celebration of accomplishment. We felt like we ended the Vietnam war, through protesting, getting killed, Kent State this was our crowning achievement. Therefore, we also liberated gay people, started the women's movement, all of that stuff. And now, just like when prohibition ended, we started celebrating. And that's what Chic was all about."

When Chic completed a triple-bill with the Clash and Blondie for a series of gigs at defunct New York club Bond's in 1981, with local B-boys invading the stage for an all-inclusive encore of "Rock the Casbah," the perceived barriers between rock and dance music became non-existent. "It was amazing," Rodgers recalls. "It was the essence of disco and punk together as a unified force, and it was just one of those kind of things that came and went. But we didn't think about it as history it's just what we do."

Various

In the Beginning There Was Rhythm (Soul Jazz, 2002)

Likely the best single-disc primer of the post-punk era, and perhaps the only place to find essential tracks like the Pop Group's "She is Beyond Good and Evil" and the Slits' "In the Beginning " without risking personal bankruptcy at the hands of eBay.

Gang of Four

Entertainment! (Warner, 1980)

For all of its frankly humourless dogma about society's moral collapse, this is a guitar record that, like Television's Marquee Moon, you can feel in your spine.

The Raincoats

Moving (Rough Trade, 1984; Geffen, 1993 out of print)

Alongside the Slits, this London group exemplified how punk allowed women to produce music that was truly their own. Moving remains one of the best examples of post-punk's cross-pollinating impulse, with "Animal Rhapsody" a dazzling declaration of female self-will set to an irresistible disco beat.

Radio 4

Gotham! (Gern Blandsten, 2002)

Two arguments in favour of the validity of guitar rock in 2002, keeping one eye on the distortion pedal and the other on the dance floor. These New York groups take up post-punk's challenge to find new ways of making the familiar unfamiliar and succeed brilliantly.

ESG

A South Bronx Story (Soul Jazz, 2000)

An incomparable sound that could only have happened by accident. Sweltering NYC funk set adrift in outer space, or left to fend for itself on the cold, grey streets of Manchester.

Delta 5

See the Whirl (Pre, 1981 out of print)

This Leeds, UK quintet leapt from their comparatively crude early singles on Rough Trade to this remarkably assured debut and, it transpired, only album. Angular and terse but also melodic and graceful (including horn arrangements and pedal steel). Someone reissue this now!

Talking Heads

Remain in Light (Sire, 1980)

Talking Heads were one of the few American rock bands enlightened and open-minded enough to absorb the influences of disco, funk, and world music in the early '80s. Produced by Brian Eno, it still sounds futuristic today, and was savvy enough in its blending of the experimental and the accessible to have been a Top 40 album.

Josef K

Young and Stupid (LTM, 2002)

Punk rock possessed of a romantic heart. This Scottish group sounded anxious and suspicious but ultimately, like idealists. "The Missionary" and "Sorry for Laughing" are dance songs for caffeine addicts a summit meeting between Captain Beefheart and Chic.

Various

Disco Not Disco (Strut, 2000)

Post-punk artists admired the oft-overlooked experimentalism of early disco (Giorgio Moroder's Donna Summer productions, for instance). When mainstream disco "died," it gained a new life in the underground, where it rediscovered its spirit of adventure. Early '80s tracks featured here by Yoko Ono, Common Sense, and Ian Dury engage the brain and the booty.