After years spent sermonising about the ill effects of globalization, progressive media outlets must begin to unearth those stories that testify to the resilience of indigenous cultures throughout the world. Hip-hop, for example, may have been born in the United States, but as it has spread around the globe, rap has become the first pan-continental folk form, unifying the struggles of disenfranchised and disaffected peoples everywhere. Nowhere is this phenomenon more distinctly audible than in Brazil, from which emanates one of the year's best compilations, Rio Baile Funk: Favela Booty Bass.

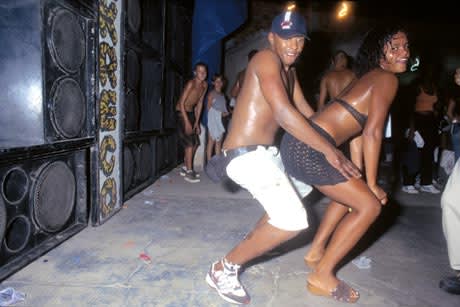

Released on Germany's Essay Recordings (available in Canada through Fusion III), Favela Booty Bass documents the street sound of Rio De Janeiro, a city with a soundclash culture reminiscent of Kingston, Jamaica. As with that Caribbean city, Rio is well known for its massive street parties, or bailes, which can draw thousands of revellers onto the streets for all-day, all-night dance parties. Since their inception in the early 70s, these celebrations have incubated a peculiarly Latinised form of African-American music, first with jazz, funk and soul now with hip-hop.

It's this latter day fascination with hip-hop specifically with 80s-era electro producers like Afrika Bambaataa and his legion of Miami-based descendants that is documented on Favela Booty Bass, a disc compiled by German DJ and music critic Daniel Haaksman. After a friend of Haaksman's brought back some Brazilian bass tapes back to him after a vacation, the Berlin-based scribe was so fascinated with the music he booked himself a trip to South America to compile tracks for the eventual compilation.

First and foremost, the music compiled on Favela Booty Bass is a rebel form, based on the same hardcore principles evident in ragga, jungle and grime: brazen sample robbery and rhythmic stridency. The last of those elements is heard in the violent collision of Miami bass-style breaks and percussive Latin rhythms sourced from samba. Mashed together under the weight of one-fingered synth riffs and local rappers' boastful chants, this is a ghetto form that simultaneously documents and transcends the horrific conditions in Rio's slums.

To North American ears, what's perhaps most shocking about this music is how seemingly mismatched are its components whether it's samba drums paired with archaic drum machines, wobbly accordion riffs laid over plodding synth refrains, or a band of rowdy carousers howling over familiar pop samples. Indeed, what's lacking from this music in virtuosity or sophistication is more than made up for by sheer force of ingenuity and passion, the disc offering listeners a glorious (albeit entirely touristic) visit to the poorest part of the Americas.

Generally acknowledged as the godfather of baile funk, Rio's DJ Marlboro first introduced Miami bass to his countrymen in the late 1980s, having brought home several records by 2 Live Crew and DJ Magic Mike, which he'd purchased on a visit to Florida. Within years, an indigenous community of music makers had encircled DJ Marlboro, most of whom are earning their first taste of intentional acclaim with their appearance on Favela Booty Bass.

While that compilation has thus far been largely confined to critical circles, all signs point toward the genre's creeping infiltration into the wider consciousness. For his part, Philadelphia-based Ninja Tune artist Diplo has released Favelas on Blast, a concussive mix of Brazilian booty music that has been doing a brisk business on the mix-tape circuit.

For those who might like to sample this stuff before purchasing it, there exists no better resource than Funky Do Morro (www.evil-wire.org/~ampere/mp3/funky), which hosts over 200 Brazilian booty bass tracks. There's much to sift through here, and much that's only novel at best, but when you happen upon a song like MC Junior and MC Leonardo's "Rap Do Centenario" a space-age soccer anthem adorned with euphoric samba cut-ups then you might well be planning your next visit to the record store, or to Brazil itself.

More than most of their Canadian counterparts, Junior, Leonardo and their cohorts seem to understand that hip-hop is necessarily a glocal form, able as they are to meld the urban imperative of its Bronx origins with the intrinsic features of their own communities. Indeed, Coca-Cola may well taste the same in São Paulo as it does in San Diego, but hip-hop cannot. For this, we are thankful.

Released on Germany's Essay Recordings (available in Canada through Fusion III), Favela Booty Bass documents the street sound of Rio De Janeiro, a city with a soundclash culture reminiscent of Kingston, Jamaica. As with that Caribbean city, Rio is well known for its massive street parties, or bailes, which can draw thousands of revellers onto the streets for all-day, all-night dance parties. Since their inception in the early 70s, these celebrations have incubated a peculiarly Latinised form of African-American music, first with jazz, funk and soul now with hip-hop.

It's this latter day fascination with hip-hop specifically with 80s-era electro producers like Afrika Bambaataa and his legion of Miami-based descendants that is documented on Favela Booty Bass, a disc compiled by German DJ and music critic Daniel Haaksman. After a friend of Haaksman's brought back some Brazilian bass tapes back to him after a vacation, the Berlin-based scribe was so fascinated with the music he booked himself a trip to South America to compile tracks for the eventual compilation.

First and foremost, the music compiled on Favela Booty Bass is a rebel form, based on the same hardcore principles evident in ragga, jungle and grime: brazen sample robbery and rhythmic stridency. The last of those elements is heard in the violent collision of Miami bass-style breaks and percussive Latin rhythms sourced from samba. Mashed together under the weight of one-fingered synth riffs and local rappers' boastful chants, this is a ghetto form that simultaneously documents and transcends the horrific conditions in Rio's slums.

To North American ears, what's perhaps most shocking about this music is how seemingly mismatched are its components whether it's samba drums paired with archaic drum machines, wobbly accordion riffs laid over plodding synth refrains, or a band of rowdy carousers howling over familiar pop samples. Indeed, what's lacking from this music in virtuosity or sophistication is more than made up for by sheer force of ingenuity and passion, the disc offering listeners a glorious (albeit entirely touristic) visit to the poorest part of the Americas.

Generally acknowledged as the godfather of baile funk, Rio's DJ Marlboro first introduced Miami bass to his countrymen in the late 1980s, having brought home several records by 2 Live Crew and DJ Magic Mike, which he'd purchased on a visit to Florida. Within years, an indigenous community of music makers had encircled DJ Marlboro, most of whom are earning their first taste of intentional acclaim with their appearance on Favela Booty Bass.

While that compilation has thus far been largely confined to critical circles, all signs point toward the genre's creeping infiltration into the wider consciousness. For his part, Philadelphia-based Ninja Tune artist Diplo has released Favelas on Blast, a concussive mix of Brazilian booty music that has been doing a brisk business on the mix-tape circuit.

For those who might like to sample this stuff before purchasing it, there exists no better resource than Funky Do Morro (www.evil-wire.org/~ampere/mp3/funky), which hosts over 200 Brazilian booty bass tracks. There's much to sift through here, and much that's only novel at best, but when you happen upon a song like MC Junior and MC Leonardo's "Rap Do Centenario" a space-age soccer anthem adorned with euphoric samba cut-ups then you might well be planning your next visit to the record store, or to Brazil itself.

More than most of their Canadian counterparts, Junior, Leonardo and their cohorts seem to understand that hip-hop is necessarily a glocal form, able as they are to meld the urban imperative of its Bronx origins with the intrinsic features of their own communities. Indeed, Coca-Cola may well taste the same in São Paulo as it does in San Diego, but hip-hop cannot. For this, we are thankful.