Remember drum & bass? Unless you're a hardcore junglist, that genre probably hasn't crossed your mind since you traded in your copy of Reprazent's New Forms or Goldie's Timeless sometime in the late '90s. Having been around for more than a decade now, drum & bass seems to have settled into its role as dance music's version of metal a nominally extremist form that rarely draws the interest of folks outside its tight-knit circle.

In the face of such rhythmically inventive forms as grime and baile funk, it's tempting to write off postmillennial drum & bass altogether, and that's just what many of the genre's former critical champions have done in the last few years. For those old-schoolers who were around when hardcore rave music first mutated into jungle, the argument against contemporary d&b goes something like this: since about 1996, the form's rhythmic complexity has been supplanted by three corrosive developments, namely a) increasing tempos; b) formulaic beat patterns (as popularised by Alex Reece's canonical two-step tune "Pulp Fiction"); and c) escalating loudness.

Over the latter half of the '90s, these three factors developed hand in hand. As tempos increased from the already swift averages of 160 beats per minute to the positively frenetic 180 BPM range, producers substituted the straightforward two-step beat signature for the more intricate break beat patterns that had once dominated the scene; at such high tempos, anything other than simple two-step drum loops would have baffled all but the most gymnastic of dancers.

With speeds up and the rolling two-step formula firmly entrenched, just about the only thing left for producers to do was to refine the sounds themselves. Thus did drum & bass become dominated not by composers, but by glorified engineers folks (like Ed Rush and Dillinja) whose greatest contributions to the form have been largely technical. From the mid-'90s onward, the scene became overrun with tracks that were not so much musical as they were coldly functional, testaments all to the might of modern-day mastering techniques.

Not coincidentally, this emphasis on fidelity has helped perpetuate the longstanding supremacy of top dogs like Goldie and Roni Size, who are among the few producers who can afford to have their records pressed to such high standards. More than any other form of dance music, drum & bass is dominated by a relatively small number of labels (like Valve and Renegade Hardware) and taste-making DJs (like Fabio and Grooverider), all of whom profit from keeping the scene squarely under their thumbs. Rumours have long abounded that the London-centric drum & bass community is run like a cartel, with the heads of the most powerful labels routinely exploiting their influence with distribution companies to discourage the efforts of smaller competitors.

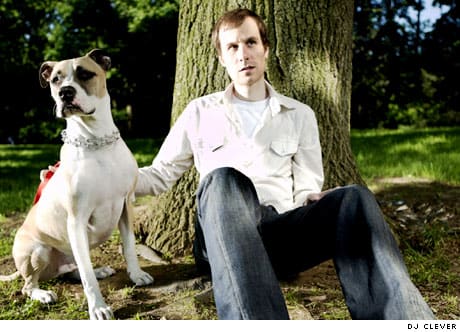

Undeterred by that ruthless protectionism, a handful of independents have started to make serious inroads in the industry, none more cunningly than New York City's Offshore Recordings. Owned and operated by Brett Cleaver (aka DJ Clever), the label has been making a joyful noise for three years now, promoting a heavily-syncopated sound that circles back to the genre's roots in funk and hip-hop. With its restrained tempos and heavily chopped-up break beats, Clever's Troubled Waters mix compilation (released in 2004) demonstrates that there's a lot more to Stateside drum & bass than the heavy-metal chicanery of Dieselboy and his ilk.

This month sees the release of Clever's newest mix, this one for Offshore's more established NYC label counterpart Breakbeat Science. Though it hews closer to the prevailing trends in big-time drum & bass, that imprint is another reliable source of the classic cut-up style old-time junglists like best. There may be no better single source of those kinds of tracks than Los Angeles's Pieter K, whose complexly-layered drums propel much of DJ DB's overlooked Exercise 4 mix, also released last year by Breakbeat Science.

Rounding out the roster of essential chop-heavy compilations is 2004's Inperspective Records in the Mix, a Knowledge magazine-mounted showcase for London's Inperspective imprint. Like their fellow Londoners behind Reinforced Records, Inperspective's producers operate on the fringes of the British scene, refusing to tailor their tunes for the anthem-crazed punters who control the scene. In a genre renowned for its ability to hit people over the head, it's nice to find labels willing to let dancers find their own room to groove.

In the face of such rhythmically inventive forms as grime and baile funk, it's tempting to write off postmillennial drum & bass altogether, and that's just what many of the genre's former critical champions have done in the last few years. For those old-schoolers who were around when hardcore rave music first mutated into jungle, the argument against contemporary d&b goes something like this: since about 1996, the form's rhythmic complexity has been supplanted by three corrosive developments, namely a) increasing tempos; b) formulaic beat patterns (as popularised by Alex Reece's canonical two-step tune "Pulp Fiction"); and c) escalating loudness.

Over the latter half of the '90s, these three factors developed hand in hand. As tempos increased from the already swift averages of 160 beats per minute to the positively frenetic 180 BPM range, producers substituted the straightforward two-step beat signature for the more intricate break beat patterns that had once dominated the scene; at such high tempos, anything other than simple two-step drum loops would have baffled all but the most gymnastic of dancers.

With speeds up and the rolling two-step formula firmly entrenched, just about the only thing left for producers to do was to refine the sounds themselves. Thus did drum & bass become dominated not by composers, but by glorified engineers folks (like Ed Rush and Dillinja) whose greatest contributions to the form have been largely technical. From the mid-'90s onward, the scene became overrun with tracks that were not so much musical as they were coldly functional, testaments all to the might of modern-day mastering techniques.

Not coincidentally, this emphasis on fidelity has helped perpetuate the longstanding supremacy of top dogs like Goldie and Roni Size, who are among the few producers who can afford to have their records pressed to such high standards. More than any other form of dance music, drum & bass is dominated by a relatively small number of labels (like Valve and Renegade Hardware) and taste-making DJs (like Fabio and Grooverider), all of whom profit from keeping the scene squarely under their thumbs. Rumours have long abounded that the London-centric drum & bass community is run like a cartel, with the heads of the most powerful labels routinely exploiting their influence with distribution companies to discourage the efforts of smaller competitors.

Undeterred by that ruthless protectionism, a handful of independents have started to make serious inroads in the industry, none more cunningly than New York City's Offshore Recordings. Owned and operated by Brett Cleaver (aka DJ Clever), the label has been making a joyful noise for three years now, promoting a heavily-syncopated sound that circles back to the genre's roots in funk and hip-hop. With its restrained tempos and heavily chopped-up break beats, Clever's Troubled Waters mix compilation (released in 2004) demonstrates that there's a lot more to Stateside drum & bass than the heavy-metal chicanery of Dieselboy and his ilk.

This month sees the release of Clever's newest mix, this one for Offshore's more established NYC label counterpart Breakbeat Science. Though it hews closer to the prevailing trends in big-time drum & bass, that imprint is another reliable source of the classic cut-up style old-time junglists like best. There may be no better single source of those kinds of tracks than Los Angeles's Pieter K, whose complexly-layered drums propel much of DJ DB's overlooked Exercise 4 mix, also released last year by Breakbeat Science.

Rounding out the roster of essential chop-heavy compilations is 2004's Inperspective Records in the Mix, a Knowledge magazine-mounted showcase for London's Inperspective imprint. Like their fellow Londoners behind Reinforced Records, Inperspective's producers operate on the fringes of the British scene, refusing to tailor their tunes for the anthem-crazed punters who control the scene. In a genre renowned for its ability to hit people over the head, it's nice to find labels willing to let dancers find their own room to groove.