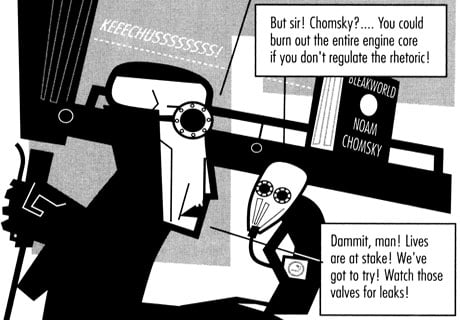

The cruel, disturbing modern world portrayed in James Turner's graphic novel debut, Nil: A Land Beyond Belief, fits nicely alongside other anti-capitalist screeds, between the bleakness of Orwell's 1984 and the exhuberant excess of Warren Ellis's Transmetropolitan, but despite these undertones, Turner insists he's not against capitalism. "I'm not against consumerism, just excessive consumption and worship of the material," he explains. "We're bombarded with buy and be happy' messages every day and most people far more than advertisers seem to realise see right through it. I prefer practical advertising. Show me how a product is useful to me, not how eternal happiness can be mine with the purchase of a toothbrush or orgasm-inducing shampoo.

"I don't buy into the conspiracy theorists who believe everyone in the West is a hapless, brainwashed, drooling consumerist zombie straight out of a Romero movie. There are satirical comments about the excesses of capitalism in Nil, sure, but the main focus of the book lies elsewhere."

That focus is protagonist Proun Nul who, after being falsely accused of murder, decides to defect to the neighbouring country of Optima, where everything is bright and cheery. But the journey, a classic grass-is-greener tale, has a transformative impact on Nul as he journeys through the land of Nil to reach his destination. "He is, as his name implies, null: ineffectual and with little discernable personality," Turner explains. "He's a bit of a hapless drone. Proun, his first name, comes from an El Lissitzky art movement series. [Project for affirmation of the New' in Russian.] Proun' art was utopian and machined."

Though trained as an illustrator, Turner's background is in communications and graphic design. "I don't suppose I thought I'd get into comics," he admits, "but they offer the chance to play with both narrative and visuals, and that was something I was interested in exploring. Adult-oriented graphic novels that deal with topics other than superheroes are becoming more popular, so doing a graphic novel seemed ideal."

In creating Nil, Turner went through the same hoops most creators do. "What turned out to be the first draft took four or five months of intense work; after that I started submitting it to publishers. I didn't get any takers, so I decided to serialise it and self-publish. I went back and revised the early parts of the book to bring them in line with the ending, sought out a printer, and was a week or two away from self-publishing when I heard back from [independent publisher] Slave Labor Graphics. I'd submitted a complete copy of the first draft to them about eight months before.

"The original format was almost comic book size. [Slave Labor] wanted to print it smaller, by about 40 percent, so I reformatted it, spent time revising the remaining pages and added a few to tie up loose ends. That all happened over several months. From start to finish it took about two years."

Turner recognises that it's a challenge to market a book with such dark themes. "The idea that only happiness sells is quite common in marketing circles. And happy books may very well sell more than sad, funny ones. But that's relative; sad stuff still sells. Maybe not as much, true, but I didn't write the book for financial reasons. That's not to say I'd mind if it sold well.

"As a dark satire, Nil was never meant to be anything other than a niche product. It was written because I was interested in the material, not because a focus group told me it would sell like hotcakes. There are over 300 million people in North America, and all I really need is a few thousand to buy out the print run. I think that there are at least that many open-minded people who might find Nil interesting. I also believe that better work is produced when you go where your mind takes you as opposed to sitting down with a committee and producing work that tries to appeal to everyone and everything. I doubt Orwell passed 1984 around a focus group before publishing it, and I do not believe Nil is really any darker. Death is nothing. Life is everything. Including the absurd."

The Memoirist

Who are we without our memories? Are we really any different from each other if we lose them? In our search to find meaning in our existence, we often come up against such questions. In his book Mnemovore, creator Ray Fawkes sets out, with co-writer Hans Rodionoff, to explore the psychology behind memory and what happens to us psychologically when we begin to lose pieces of it.

On the surface, the book tells the tale of Kaley, a snowboard sensation who loses her memory after an accident, but underneath that lies a deeper exploration of the psyche. "There's a lot more to this story than an injury that ends an athletic career," Fawkes says. "Mnemovore is about what it is that makes us what we are, and what we think we are. How much of the self is assembled from memory, and how much could (or should) we function without it? Pieces of us fade into the past with every step in time. What is it that keeps us together as our minds and memories corrode?"

Originally published independently by Fawkes, in its new version Mnemovore shares credit with his new Vertigo collaborators. "Something like 200 copies of the indie version are out there, all over the place I was selling it for about six months before Hans Rodionoff and Vertigo came to me and we started to talk about putting a revised version together for mass-market sale. We assembled the team that is currently working on the book, and I was happy to share creative ownership with my co-writer, Hans, and artist, Mike Huddleston."

"I don't buy into the conspiracy theorists who believe everyone in the West is a hapless, brainwashed, drooling consumerist zombie straight out of a Romero movie. There are satirical comments about the excesses of capitalism in Nil, sure, but the main focus of the book lies elsewhere."

That focus is protagonist Proun Nul who, after being falsely accused of murder, decides to defect to the neighbouring country of Optima, where everything is bright and cheery. But the journey, a classic grass-is-greener tale, has a transformative impact on Nul as he journeys through the land of Nil to reach his destination. "He is, as his name implies, null: ineffectual and with little discernable personality," Turner explains. "He's a bit of a hapless drone. Proun, his first name, comes from an El Lissitzky art movement series. [Project for affirmation of the New' in Russian.] Proun' art was utopian and machined."

Though trained as an illustrator, Turner's background is in communications and graphic design. "I don't suppose I thought I'd get into comics," he admits, "but they offer the chance to play with both narrative and visuals, and that was something I was interested in exploring. Adult-oriented graphic novels that deal with topics other than superheroes are becoming more popular, so doing a graphic novel seemed ideal."

In creating Nil, Turner went through the same hoops most creators do. "What turned out to be the first draft took four or five months of intense work; after that I started submitting it to publishers. I didn't get any takers, so I decided to serialise it and self-publish. I went back and revised the early parts of the book to bring them in line with the ending, sought out a printer, and was a week or two away from self-publishing when I heard back from [independent publisher] Slave Labor Graphics. I'd submitted a complete copy of the first draft to them about eight months before.

"The original format was almost comic book size. [Slave Labor] wanted to print it smaller, by about 40 percent, so I reformatted it, spent time revising the remaining pages and added a few to tie up loose ends. That all happened over several months. From start to finish it took about two years."

Turner recognises that it's a challenge to market a book with such dark themes. "The idea that only happiness sells is quite common in marketing circles. And happy books may very well sell more than sad, funny ones. But that's relative; sad stuff still sells. Maybe not as much, true, but I didn't write the book for financial reasons. That's not to say I'd mind if it sold well.

"As a dark satire, Nil was never meant to be anything other than a niche product. It was written because I was interested in the material, not because a focus group told me it would sell like hotcakes. There are over 300 million people in North America, and all I really need is a few thousand to buy out the print run. I think that there are at least that many open-minded people who might find Nil interesting. I also believe that better work is produced when you go where your mind takes you as opposed to sitting down with a committee and producing work that tries to appeal to everyone and everything. I doubt Orwell passed 1984 around a focus group before publishing it, and I do not believe Nil is really any darker. Death is nothing. Life is everything. Including the absurd."

The Memoirist

Who are we without our memories? Are we really any different from each other if we lose them? In our search to find meaning in our existence, we often come up against such questions. In his book Mnemovore, creator Ray Fawkes sets out, with co-writer Hans Rodionoff, to explore the psychology behind memory and what happens to us psychologically when we begin to lose pieces of it.

On the surface, the book tells the tale of Kaley, a snowboard sensation who loses her memory after an accident, but underneath that lies a deeper exploration of the psyche. "There's a lot more to this story than an injury that ends an athletic career," Fawkes says. "Mnemovore is about what it is that makes us what we are, and what we think we are. How much of the self is assembled from memory, and how much could (or should) we function without it? Pieces of us fade into the past with every step in time. What is it that keeps us together as our minds and memories corrode?"

Originally published independently by Fawkes, in its new version Mnemovore shares credit with his new Vertigo collaborators. "Something like 200 copies of the indie version are out there, all over the place I was selling it for about six months before Hans Rodionoff and Vertigo came to me and we started to talk about putting a revised version together for mass-market sale. We assembled the team that is currently working on the book, and I was happy to share creative ownership with my co-writer, Hans, and artist, Mike Huddleston."