Back in 1970, the burgeoning genre of electronic music was still trying to find its own identity. For the earlier part of the century, it had primarily been employed by classical performers and experimental composers, from Clara Rockmore's virtuoso Theremin playing to the surreal synthesis of Edgard Varèse and the tape-collages of Pierre Schaeffer, along with some employment in early sci-fi scores like Forbidden Planet and Doctor Who. Bob Moog's invention of the modular synthesizer made it possible to bring synths home, and the cutting edge sounds started to creep into the American mainstream in rock tracks by the likes of the Doors, the Monkees and the Byrds. Yet, they were still largely treated as a novelty or as an accompaniment to traditional pop arrangements.

The first record of electronic music to go gold was Wendy Carlos's 1968 debut, Switched on Bach. The album of Bach tunes, arranged for the Moog won three Grammys; this being the golden age of exploito LPs (see artists like the Id and the Animated Egg, and the myriad variations thereof), Moog records became a thing after that, and collections of hastily arranged country, rock and other such popular covers were churned out.

The French, as usual, were ahead of the game. Jean-Jacques Perrey had his mind blown by Georges Jenny's vibrato-capable Ondioline tube synth and caught the tape-loop bug from Pierre Schaeffer. Perrey put them to work with German-American composer Gershon Kingsley, whom he met while on staff as an arranger at Vanguard Records. Then primarily known as a folk label, yet never afraid to take a chance on now sounds, Vanguard put out Perrey and Kingsley's fabulously titled collaborative debut The In Sound from Way Out! in 1966. The duo followed it up a year later with Kaleidoscopic Vibrations, one of the first pop recordings to feature the Moog, having been released over a year earlier than Switched on Bach.

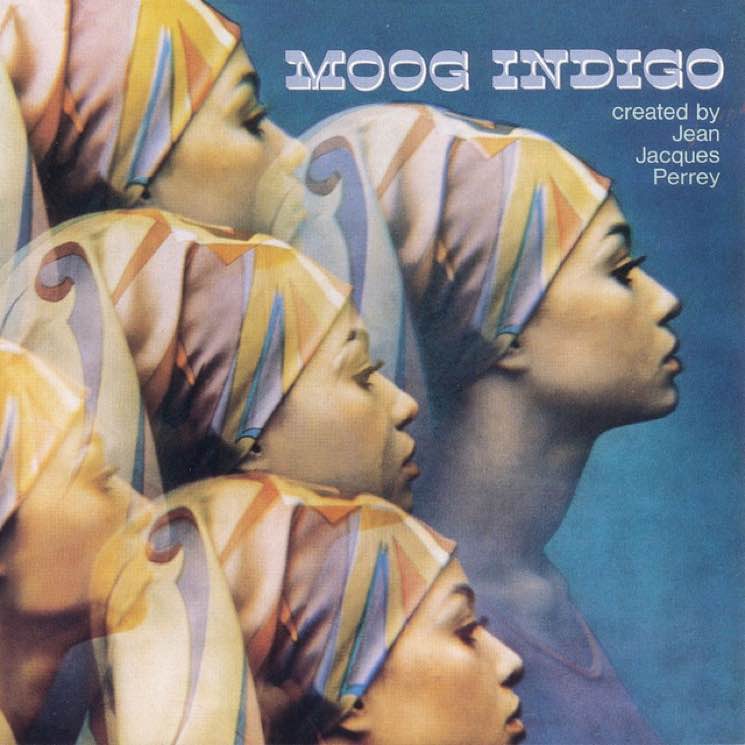

By the time Perrey got around to Moog Indigo in 1970, he had a few albums under his belt, solo and otherwise, and tons of experience with the Moog, Ondioline and tape-loops. He had all the tools to create his masterpiece.

Granted, there were still quite a few contextual tropes to be found here. The expected renditions of Rimsky-Korsakov's "Flight of the Bumblebee" and Broadway smash "Hello, Dolly!" are almost too precious for their own good, as is the cover of Beethoven's "Turkish March," retitled "The Elephant Never Forgets" (which was subsequently used as the theme of a Mexican sitcom).

"Passport to the Future" borrows melodically from Joe Meek's instrumental rock hit "Telstar," while "18th Century Puppet" has clear nods to baroque composition. "Country Rock Polka" is a medley of familiar folksy tunes, predating "Weird Al" Yankovic's comical polka medleys by over a decade. The album title itself is a reference to a Duke Ellington jazz standard, while rock instrumentation plays a large role in all of its arrangements.

Despite all this, there were clear hints of where the genre could go. The persistent, infectious presence of Perrey's distinctive acousmatic blend of spliced and diced synth gestures and springy, ratchety Looney Tunes-esque sound effects remind the listener who is in the driver seat, with all due respect to the many contributions of percussionist Harry Breuer, Pat Prilly (aka Perrey's daughter Patricia Leroy), Andy Badale (aka Twin Peaks composer Angelo Badalamenti) and others who helped realize the album's creation.

The opening "Soul City" is a slab of the psychedelic funky business that Parliament would go on to perfect. "Cat in the Night" has a subtle glaze of darkness, rarely heard on Perrey's typically joyful recordings, which would perfectly suit a gritty cop drama from the period. "Gossipo Profundo" is sheer arpeggiated lunacy, with masculine and feminine vocal cuts delivering its manic melody in vivid stereo.

"E.V.A." is the gooey center of the album. Driven by tubular bells, cheeky, bubbling synths and scorching electric guitar, all you need to do is beef up its broken drum beat and add a choice drop with a warping bass line, and this baby is still of the now. It had the vibe of booty-shaking bass worship at a time when dub was still being codified in Jamaican dancehalls. The fact that "E.V.A." would go on to be sampled by Gang Starr, Dr. Octagon, Danny Breaks, Luke Vibert, Pusha T and many more speaks to its lasting brilliance.

Moog Indigo has yet to be picked clean, though. For the first time since its release, Vanguard has repressed this thing to bold 180 gram vinyl, remastered from the original analog tapes and faithfully reproduced to original audiophile standards with no added bells or whistles to distract from the proto-futuristic genius contained in its grooves. There are countless creative opportunities to be found in this half-hour trip that have yet to be fully explored, and for the rest of us, it's an opportunity to experience a landmark album of electronic pop that stands the test of time.

(Vanguard)The first record of electronic music to go gold was Wendy Carlos's 1968 debut, Switched on Bach. The album of Bach tunes, arranged for the Moog won three Grammys; this being the golden age of exploito LPs (see artists like the Id and the Animated Egg, and the myriad variations thereof), Moog records became a thing after that, and collections of hastily arranged country, rock and other such popular covers were churned out.

The French, as usual, were ahead of the game. Jean-Jacques Perrey had his mind blown by Georges Jenny's vibrato-capable Ondioline tube synth and caught the tape-loop bug from Pierre Schaeffer. Perrey put them to work with German-American composer Gershon Kingsley, whom he met while on staff as an arranger at Vanguard Records. Then primarily known as a folk label, yet never afraid to take a chance on now sounds, Vanguard put out Perrey and Kingsley's fabulously titled collaborative debut The In Sound from Way Out! in 1966. The duo followed it up a year later with Kaleidoscopic Vibrations, one of the first pop recordings to feature the Moog, having been released over a year earlier than Switched on Bach.

By the time Perrey got around to Moog Indigo in 1970, he had a few albums under his belt, solo and otherwise, and tons of experience with the Moog, Ondioline and tape-loops. He had all the tools to create his masterpiece.

Granted, there were still quite a few contextual tropes to be found here. The expected renditions of Rimsky-Korsakov's "Flight of the Bumblebee" and Broadway smash "Hello, Dolly!" are almost too precious for their own good, as is the cover of Beethoven's "Turkish March," retitled "The Elephant Never Forgets" (which was subsequently used as the theme of a Mexican sitcom).

"Passport to the Future" borrows melodically from Joe Meek's instrumental rock hit "Telstar," while "18th Century Puppet" has clear nods to baroque composition. "Country Rock Polka" is a medley of familiar folksy tunes, predating "Weird Al" Yankovic's comical polka medleys by over a decade. The album title itself is a reference to a Duke Ellington jazz standard, while rock instrumentation plays a large role in all of its arrangements.

Despite all this, there were clear hints of where the genre could go. The persistent, infectious presence of Perrey's distinctive acousmatic blend of spliced and diced synth gestures and springy, ratchety Looney Tunes-esque sound effects remind the listener who is in the driver seat, with all due respect to the many contributions of percussionist Harry Breuer, Pat Prilly (aka Perrey's daughter Patricia Leroy), Andy Badale (aka Twin Peaks composer Angelo Badalamenti) and others who helped realize the album's creation.

The opening "Soul City" is a slab of the psychedelic funky business that Parliament would go on to perfect. "Cat in the Night" has a subtle glaze of darkness, rarely heard on Perrey's typically joyful recordings, which would perfectly suit a gritty cop drama from the period. "Gossipo Profundo" is sheer arpeggiated lunacy, with masculine and feminine vocal cuts delivering its manic melody in vivid stereo.

"E.V.A." is the gooey center of the album. Driven by tubular bells, cheeky, bubbling synths and scorching electric guitar, all you need to do is beef up its broken drum beat and add a choice drop with a warping bass line, and this baby is still of the now. It had the vibe of booty-shaking bass worship at a time when dub was still being codified in Jamaican dancehalls. The fact that "E.V.A." would go on to be sampled by Gang Starr, Dr. Octagon, Danny Breaks, Luke Vibert, Pusha T and many more speaks to its lasting brilliance.

Moog Indigo has yet to be picked clean, though. For the first time since its release, Vanguard has repressed this thing to bold 180 gram vinyl, remastered from the original analog tapes and faithfully reproduced to original audiophile standards with no added bells or whistles to distract from the proto-futuristic genius contained in its grooves. There are countless creative opportunities to be found in this half-hour trip that have yet to be fully explored, and for the rest of us, it's an opportunity to experience a landmark album of electronic pop that stands the test of time.