This is a very different piece than it was on the night of January 10, when I was putting the finishing touches on it.

When I started writing it, it was after spending the last two months completely immersed in Bowie's life and work. I spent my winter holidays reading Marc Spitz's incredible Bowie: A Biography in anticipation; I listened to every single record front-to-back, multiple times, including both Tin Machine albums; I rewatched episodes of Extras and Flight of the Conchords that featured Bowie, just because.

So when, at around 1:40 a.m. EST on January 11, I decided I would go to sleep and edit this piece the next day, I was shaken to find that he'd died — probably while I was writing about Blackstar, an album that I'd already decided was essential, but had now taken on incredible new meaning.

Although this intro is new, and I had to rewrite my entry on Blackstar, this piece is, otherwise, exactly as it would have been posted as planned, were Bowie still with us. Whether you're just discovering Bowie now, or you're a long-time fan, I hope this piece is even half as enjoyable to read as it was to write.

Goodbye, David Bowie. You've really made the grade.

There are few musical bodies of work as intimidating as David Bowie's. Bob Dylan, Miles Davis, Johnny Cash and James Brown come to mind, to name a few, but there are few musicians with a discography that spans as much time, explores as many genres and features as many bona fide classics as those of the man born David Robert Jones. Ever an explorer and experimentalist, Bowie made his share of missteps across his almost 50 years of releasing albums, but his creative restlessness ensured that even when his music wasn't innovative, it was utterly, inarguably fascinating.

Much of Bowie's best work has been with collaborators — Mick Rock, Carlos Alomar, Brian Eno, Nile Rodgers — but at the centre of his success has always been his innate ability to channel the work of others through his prismatic sensibilities, turning outside influences into unique hybrid sounds that always still manage to sound like Bowie.

From the psych-folk freak-outs of his early solo work to the jazz-infused, dark soul meditations of this month's Blackstar, Bowie has covered a lot of sonic territory, which can make finding a gateway into his work difficult. To help, we've picked Bowie's 10 best records below, contextualizing them within his massive discography as part of our ongoing Essential Guide series. If you've already listened to those, read on for further listening suggestions and which of Bowie's records to avoid.

Essential Albums:

10. 1. Outside

(1995)

Contrarians will argue, but it's hard to deny that Bowie's catalogue took a turn for the worse after 1980's Scary Monsters (even if, like me, you'll still go to bat for 1983's hit-fest Let's Dance). As such, a favourite Bowie fan pastime is to argue which record of his since that year stands as his best. For me, that record is 1. Outside.

After his regrettable 1980s, Bowie cleansed his palate by starting a (slightly less regrettable) rock'n'roll band (Tin Machine, which we'll get to later), then returned to form with 1993's Black Tie White Noise, a record whose reputation has grown in recent years. To 2016 ears, though, much of Black Tie still suffers from the cheesy production that made his late '80s work so unbearable, even if the songs are better.

1. Outside, his last collaboration with Brian Eno, is the sound of Bowie finally shaking free of that decade, finding the influences — industrial on "The Heart's Filthy Lesson," jazz on "A Small Plot of Land," ambient on "Wishful Beginnings," drum & bass on highlight "Hallo Spaceboy" — that would shape the next, better decade of his career.

At 75 minutes, it's a little bloated, and the elaborate concept weighs it down with narrative interludes, but 1. Outside remains a beguiling record, and something of a Rosetta Stone for Bowie's recorded output up until 2003's Reality.

9. Space Oddity

(1969)

Bowie's first album following the failure of his 1967 Deram Records solo debut is sometimes seen as a one-hit record — yes, the one with "Space Oddity," about Major Tom — but if you've spent any time with Space Oddity, that's a hard sentiment to agree with. Besides the iconic title track, there's the gently acoustic and scratchy-voiced "Letter to Hermione," nine-minute psych odyssey "Cygnet Committee," the theatrical "Wild Eyed Boy From Freecloud" and the urgent, pleading "God Knows I'm Good" to demonstrate Bowie's already formidable songwriting strength and the wealth of styles at his command.

The theatrical and melodic aspects of Space Oddity set the blueprint for future classics The Man Who Sold the World and Hunky Dory, and though Bowie would revisit these same styles with a few more years' experience and confidence on that latter album in 1971, being the predecessor to a masterpiece doesn't make Space Oddity any less of one itself — especially if towering closer "Memory Of A Free Festival" counts for anything.

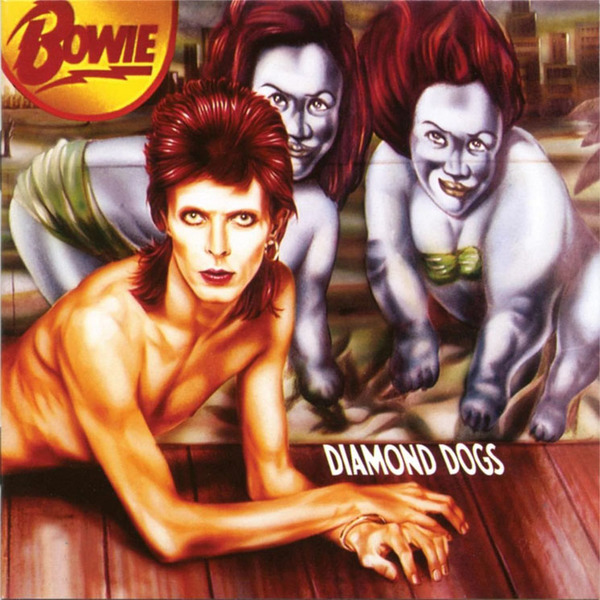

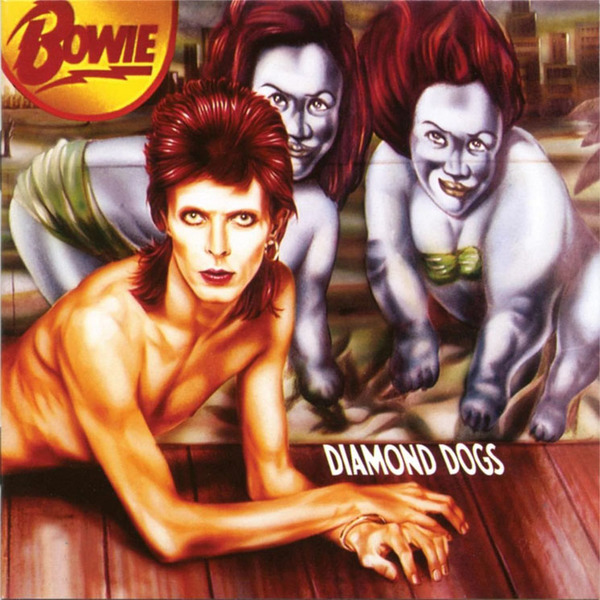

8. Diamond Dogs

(1974)

In 1973, Bowie started writing a musical based on George Orwell's 1984; when Orwell's widow denied him the rights to use the novel, Bowie quickly turned the songs into an album-length exploration of a dystopian future set in the rusted, broken-down Hunger City and named it Diamond Dogs.

Diamond Dogs features the icon working at the peak of his powers, both conceptually and musically; Hunger City is a loose enough narrative that it encompasses all of the songs on Diamond Dogs, but it still hangs together nicely, giving the album a pervasive sense of nihilistic dread and darkness that make the songs here — some of Bowie's best — intoxicating.

Bowie himself chose the "Sweet Thing/Candidate/Sweet Thing (Reprise)" suite as the second track to his self-curated iSelect compilation in 2008, and it remains some of his best, most dramatic songwriting to date. That suite sits alongside the dark disco of "1984," "Big Brother," which features the best bridge of Bowie's career (it's at 2:14) and fan favourite "Rebel Rebel," all of which easily make Diamond Dogs Bowie's most underrated record.

7. Station to Station

(1976)

Between the excellent Philadelphia soul-inspired Young Americans and his revered Berlin trilogy lies Station to Station, a six-song, slow-burning, coked-out masterpiece that harnesses both the jittery paranoia of Diamond Dogs and the soulful groove of its 1975 predecessor to summon the "return" of one of Bowie's most famous characters: the Thin White Duke.

The ten-minute opening title track is worth the price of admission alone. After over three minutes of train sounds, ominous piano plunks and swaggering rhythm, Bowie finally introduces himself: "The return of the Thin White Duke, throwing darts in lovers' eyes." Then, at 5:15, it all tumbles together into a disco epic that addresses cocaine and love before acknowledging that it's "too late to be grateful."

"Golden Years" and "TVC15" flex the funky muscle that defined Young Americans' best tracks, while ballads like "Word on a Wing" and standard "Wild is the Wind" give the album a crucial emotional heft. Station to Station is an elegant, groovy and sophisticated record that looks both backwards at the first half of Bowie's incredible 1970s and forward to the innovation of his next trilogy.

6. Scary Monsters

(1980)

After years of experimentation in Berlin with Brian Eno, Bowie returned to a more straightforward pop sound, but not without applying what he'd learned. The result was Scary Monsters, one of Bowie's most commercially successful records and an encapsulation of his '70s work that showed strains of glam and soul ("Fashion") alongside more dissonant ("It's No Game (Part 1)") and Eno-esque compositions ("Teenage Wildlife").

At the centre of it all is "Ashes to Ashes," a pop masterpiece that attained pop ubiquity without sacrificing an iota of weirdness, all while referring back to Major Tom, the hero of "Space Oddity" now turned junkie, in accordance with the turn of 1960s optimism into late '70s, post-Watergate pessimism.

Perhaps it's this sense of coming full circle, however darkly, that contributes to Scary Monsters' reputation as Bowie's last masterpiece, but there's a sense of purpose and cohesion here that even the excellent (but more hit-centric) Let's Dance can't touch. This is Bowie at his unique, beguiling best.

5. Blackstar

(2016)

We already loved Blackstar upon its release — I called it "a deeper, more affecting Bowie record" that embraces the past "while sounding unsure about the dark future"; Michael Rancic's prescient review called it a "defining statement from someone who isn't interested in living in the past, but rather, for the first time in a while, waiting for everyone else to catch up" — but in the context of Bowie's passing, it's hard not to consider it a masterpiece. This is a swan song in the truest sense of the term: Bowie wrote the album knowing he was about to die.

It's easy to hear in retrospect, especially on the title track, when he sings: "Something happened on the day he died/ Spirit rose a metre and stepped aside/ Somebody else took his place and bravely cried, 'I'm a black star/ I'm a black star.'" A black (dwarf) star is a star that's about to die, as it "no longer emits significant heat or light." In the video for "Blackstar," Bowie's wearing a blindfold. He sings about a "solitary candle." That context adds even more weight and significance to Blackstar, the first Bowie record in a long while that felt genuinely unhurried, at ease and self-assured.

It's a perfect, generous way for an artist like him to say goodbye. Rather than discuss what he was going through, Bowie turned his last few breaths of life into art. He knew he was leaving, so he created something of it, as he's always done, as he ever was compelled to. Because that is what creators do.

4. "Heroes"

(1977)

The second album in Bowie's Berlin trilogy is, depending on your mood, every bit as good as its predecessor, Low. The more emphatic record of the two, "Heroes" is as stark as its monochromatic cover art, especially in the juxtaposition between its sides: "Heroes" predicts the sound of Scary Monsters with its opening trio of muscly, riff-centric anthems, "Beauty and the Beast," "Joe the Lion" and the famous title track; on the record's ambient second side, "V-2 Schneider" is more upbeat, "Sense of Doubt" is more ominous and "Moss Garden" is more calming, respectively, than anything on Low.

This is all to establish just how good "Heroes" had to be; while a listener hearing Bowie's records in order of release might expect diminishing returns on the second of a trilogy, "Heroes" provides a deeper exploration of the song structures established on Low. It also boasts title track "Heroes," still one of Bowie's best and most iconic songs, and one that provided the "tasteful anthem" template for decades to come. Lest you find it cheesy, remember that the song was inspired by the idea of a couple living on either side of the divided Germany, forced to meet at the Berlin Wall; in 1977, when Bowie was living there, looking out his window at the wall every day, that meant risking death for love and freedom.

3. Hunky Dory

(1971)

In 1971, Hunky Dory formally announced Bowie's arrival as a genius after having hinted at the fact with Space Oddity and his heavier, more focused The Man Who Sold the World. Here, Bowie puts all his talents to work, in a scattered showcase of irrepressibly exuberant brilliance that can barely contain itself; Bowie jumps from style to style here seemingly just to show that he can.

And good lord, the songs: The elegant musical theatre bent of "Life on Mars" and "Oh! You Pretty Things" are remnants from Bowie's more music hall-influenced early style; "Andy Warhol" is a sparse, melodic tribute to the artist that showcases Bowie's playful side; "Queen Bitch" anticipates the glam rock of Bowie's next two albums so well that it nearly bests them; "Changes" remains the standard soundtrack to youth feeling that familiar, recurring sense of derision and disapproval from an older, established generation.

By this point, we're dealing with masterpieces only, and to rank them is nearly impossible — on any given day, Hunky Dory may be my favourite Bowie album. It's a collection of some of his best songs ever, but had yet to learn how to present them in a way that caught the world's imagination; a year later, he'd do exactly that.

2. Low

(1977)

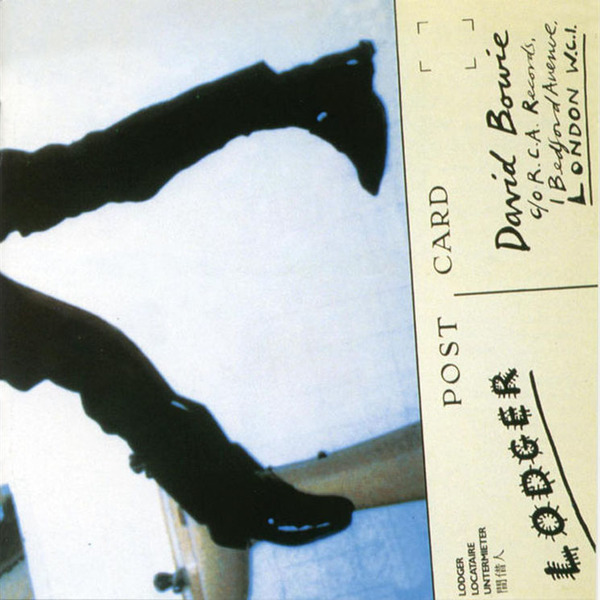

After hitting rock bottom in Los Angeles, Bowie sought escape — both from his destructive cocaine habit and the isolation of that sprawling city — in Berlin, Germany. While there, Bowie met with ex-Roxy Music performer and producer Brian Eno to record a trilogy of albums (rounded out by "Heroes" and Lodger, though the latter was actually recorded in New York) that pushed far beyond the borders of what he'd recorded to date. Low was the surprising first of them, a record that, when it was delivered to RCA in mid-1976, seemed so out of left field that the label issued a best-of compilation (ChangesOneBowie) in its stead, before finally releasing the LP in January the following year.

On Low's first side, Bowie confronts his L.A. demons, singing about depression, loneliness and addiction in spiky, three-minute pop songs like "Breaking Glass," "Sound and Vision" and "Always Crashing in the Same Car." The second side was comprised of slow, ruminative instrumentals like "Warszawa," "Art Decade," "Weeping Wall" and "Subterraneans," all of which were marked by a sense of desperation, melancholy or both.

The sounds were arrived at with the aid of Eno's famous Oblique Strategies cards, which suggested, depending on the card, that the duo "Honor thy error as a hidden intention." The cards provided inspiration, and encouraged the duo to challenge and re-think their methods and modes as often as possible.

The result was an album that, to borrow a quote from modern composer Philip Glass, created "an art within the realm of popular music." The album resonated with artists across the UK, and reverberations of its influence are still felt today, whether in pop, ambient or drone music.

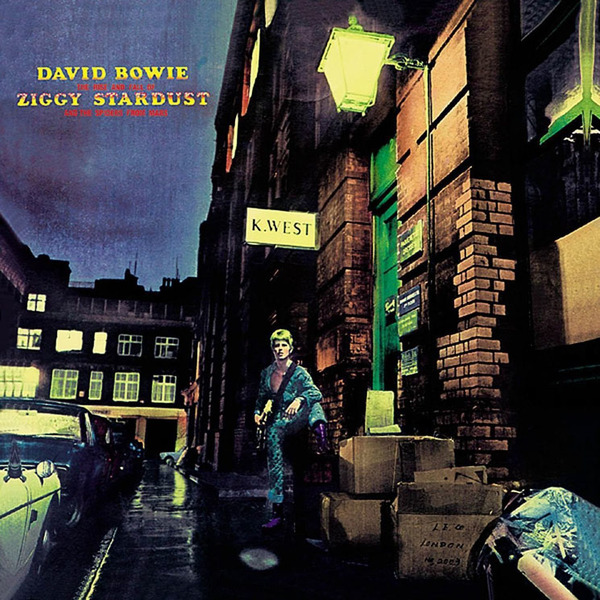

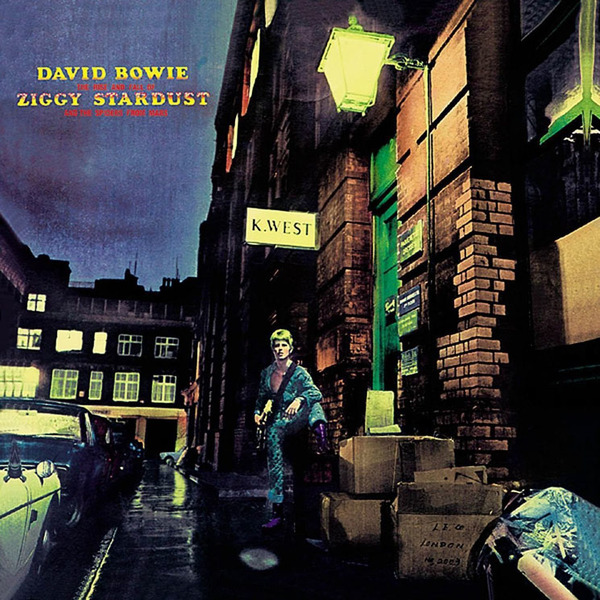

1. The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars

(1972)

At this point, there's not much left to write about Bowie's undeniable 1972 classic, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, and that made placing it at number one difficult.

As a hardcore Bowie fan, it felt too easy to call Bowie's most famous album his most essential, but then I realized that, hey: That instinct is bullshit. If someone asked me for the Bowie album to start with, I wouldn't play them my favourite Bowie record, Low, or Hunky Dory. I would give them The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars.

When I think of a Bowie record to put on, Ziggy doesn't occur to me; it's too ubiquitous, I think, or I tell myself I've heard it too many times. But then I hear those drums at the beginning of "Five Years," which build so slowly and perfectly; the crunchy, distorted opening chords and subdued acoustic verses of "Moonage Daydream"; the way the news bulletin-esque, single-note guitar wailing leads into the perfect, soaring chorus of "Starman." As much a collection of strong, standalone singles as a cohesive, narrative-based full-length statement, Ziggy Stardust not only put David Bowie on the road to stardom and helped establish glam-rock, but popularized the pop music alter ego that's been ubiquitous since.

The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars is a timeless album, and the perfect introduction to one of the century's most inventive and fascinating artists.

What to Avoid:

Bowie's first, self-titled 1967 record, for the now-defunct Deram, is a novel look at the young genius, but it's so hokey that when cheeky NME readers flooded the request phone line for his Sound + Vision tour to ensure he played that album's "The Laughing Gnome," he knew it was a joke and declined. His other early misstep, Pinups — perhaps the only inessential record he released in the 1970s — is neat for hardcore fans, but lacks the dynamism to entice more casual listeners.

It's a cliché that Bowie lost the plot in the 1980s, but it's hard to anticipate just how much until you actually listen to 1984's Tonight and 1987's Never Let Me Down, on which Bowie's first lacklustre songwriting efforts also suffer from tinny production and some of his most cringe-worthy style crossover experiments (blue-eyed pop-reggae, anyone?).

In retrospect, it's apparent that Tin Machine, the anachronistic rock'n'roll band Bowie founded at the end of the '80s, was a smart and necessary move, but their two records still haven't aged very well. The first is worth a listen, but Tin Machine II is utterly skippable, and neither are particularly crucial to understanding Bowie better. His return to solo fare, 1993's Black Tie White Noise, features slightly better songwriting, but it's only marginally better than his two '80s solo blunders, despite being seen as a return to form (he'd do so two years later, on 1. Outside).

Bowie spent most of the next decade re-finding his adventurous, more sure-footed musical self, putting out a series of albums that ranged from good to great until 2003, when he released his last record for a decade. His 2013 return, The Next Day, was a much welcomed one, and it has some stunning moments — "The Stars (Are Out Tonight)" and "Where Are We Now?" particularly — but in the grand scheme of things, it doesn't offer much that, say, 1999's 'hours…' doesn't.

Further Listening:

Basically any David Bowie album not yet mentioned is worth investigating — 1973's Aladdin Sane is an excellent, even glammier Ziggy Stardust exercise; 1983's Let's Dance is Bowie at his brash pop star best, especially on "Modern Love" and "Cat People (Putting Out Fire)"; the oft-maligned Earthling finds Bowie fully embracing drum & bass, and while some accuse it of dilettantism, close listening to the songwriting reveals some of Bowie's most formidable work — but there are a few that stand out even more strongly.

The Man Who Sold the World (1971) is the formative bridge between Space Oddity and Hunky Dory, and finds Bowie tackling some of his most poignant subject matter, as he explores war, religion and mental illness across bluesy and hard-rocking instrumentals. Young Americans, his 1975 foray into Philadelphia soul, is just as essential; the record provides the funk and soul context for the latter half of his 1970s work, and the joyous title track is one of Bowie's best-ever songs.

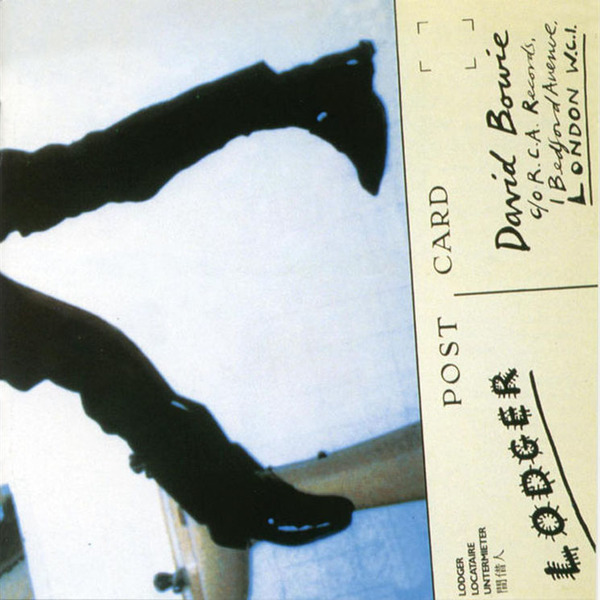

1979's Lodger is the most overlooked record of Bowie's Berlin trilogy (though it was actually recorded in the U.S.), and though it's a little different — there's no instrumental second side, for example — it's an incredible record that harnesses the sound of those Eno sessions for more a straightforward, worldly set of songs. The Berlin sound would also permeate Bowie's 1993 soundtrack to the BBC's four-part TV serial The Buddha of Suburbia, a lost gem that features gorgeous ambient pieces ("Sex and the Church," "The Mysteries"), as well as a number of more traditional pop songs ("Strangers When We Meet") that blow that year's Black Tie White Noise out of the water.

1999's 'hours…', 2002's Heathen and 2003's Reality weren't beloved upon their release (except maybe the stately Heathen), but in the decade since, they've aged well, as they showcase more mature songwriting and fewer production tricks. These records are pure neo-classicist Bowie, and while they're not quite essential, they're satisfying listens.

Critics have tended to be hard on Bowie's live albums, but for those interested, the bootleg-turned-official release Live Santa Monica '72 is perhaps the best, as it captures a young, energized Bowie with something to prove in the wake of his struggle to find success up until Ziggy Stardust. 1974's David Live is a glammy, post-Diamonds Dogs affair, and 1978's fascinating Stage, released in the midst of his Berlin phase, finds the musician attempting to weave his more experimental material in with his early '70s classics.

When I started writing it, it was after spending the last two months completely immersed in Bowie's life and work. I spent my winter holidays reading Marc Spitz's incredible Bowie: A Biography in anticipation; I listened to every single record front-to-back, multiple times, including both Tin Machine albums; I rewatched episodes of Extras and Flight of the Conchords that featured Bowie, just because.

So when, at around 1:40 a.m. EST on January 11, I decided I would go to sleep and edit this piece the next day, I was shaken to find that he'd died — probably while I was writing about Blackstar, an album that I'd already decided was essential, but had now taken on incredible new meaning.

Although this intro is new, and I had to rewrite my entry on Blackstar, this piece is, otherwise, exactly as it would have been posted as planned, were Bowie still with us. Whether you're just discovering Bowie now, or you're a long-time fan, I hope this piece is even half as enjoyable to read as it was to write.

Goodbye, David Bowie. You've really made the grade.

There are few musical bodies of work as intimidating as David Bowie's. Bob Dylan, Miles Davis, Johnny Cash and James Brown come to mind, to name a few, but there are few musicians with a discography that spans as much time, explores as many genres and features as many bona fide classics as those of the man born David Robert Jones. Ever an explorer and experimentalist, Bowie made his share of missteps across his almost 50 years of releasing albums, but his creative restlessness ensured that even when his music wasn't innovative, it was utterly, inarguably fascinating.

Much of Bowie's best work has been with collaborators — Mick Rock, Carlos Alomar, Brian Eno, Nile Rodgers — but at the centre of his success has always been his innate ability to channel the work of others through his prismatic sensibilities, turning outside influences into unique hybrid sounds that always still manage to sound like Bowie.

From the psych-folk freak-outs of his early solo work to the jazz-infused, dark soul meditations of this month's Blackstar, Bowie has covered a lot of sonic territory, which can make finding a gateway into his work difficult. To help, we've picked Bowie's 10 best records below, contextualizing them within his massive discography as part of our ongoing Essential Guide series. If you've already listened to those, read on for further listening suggestions and which of Bowie's records to avoid.

Essential Albums:

10. 1. Outside

(1995)

Contrarians will argue, but it's hard to deny that Bowie's catalogue took a turn for the worse after 1980's Scary Monsters (even if, like me, you'll still go to bat for 1983's hit-fest Let's Dance). As such, a favourite Bowie fan pastime is to argue which record of his since that year stands as his best. For me, that record is 1. Outside.

After his regrettable 1980s, Bowie cleansed his palate by starting a (slightly less regrettable) rock'n'roll band (Tin Machine, which we'll get to later), then returned to form with 1993's Black Tie White Noise, a record whose reputation has grown in recent years. To 2016 ears, though, much of Black Tie still suffers from the cheesy production that made his late '80s work so unbearable, even if the songs are better.

1. Outside, his last collaboration with Brian Eno, is the sound of Bowie finally shaking free of that decade, finding the influences — industrial on "The Heart's Filthy Lesson," jazz on "A Small Plot of Land," ambient on "Wishful Beginnings," drum & bass on highlight "Hallo Spaceboy" — that would shape the next, better decade of his career.

At 75 minutes, it's a little bloated, and the elaborate concept weighs it down with narrative interludes, but 1. Outside remains a beguiling record, and something of a Rosetta Stone for Bowie's recorded output up until 2003's Reality.

9. Space Oddity

(1969)

Bowie's first album following the failure of his 1967 Deram Records solo debut is sometimes seen as a one-hit record — yes, the one with "Space Oddity," about Major Tom — but if you've spent any time with Space Oddity, that's a hard sentiment to agree with. Besides the iconic title track, there's the gently acoustic and scratchy-voiced "Letter to Hermione," nine-minute psych odyssey "Cygnet Committee," the theatrical "Wild Eyed Boy From Freecloud" and the urgent, pleading "God Knows I'm Good" to demonstrate Bowie's already formidable songwriting strength and the wealth of styles at his command.

The theatrical and melodic aspects of Space Oddity set the blueprint for future classics The Man Who Sold the World and Hunky Dory, and though Bowie would revisit these same styles with a few more years' experience and confidence on that latter album in 1971, being the predecessor to a masterpiece doesn't make Space Oddity any less of one itself — especially if towering closer "Memory Of A Free Festival" counts for anything.

8. Diamond Dogs

(1974)

In 1973, Bowie started writing a musical based on George Orwell's 1984; when Orwell's widow denied him the rights to use the novel, Bowie quickly turned the songs into an album-length exploration of a dystopian future set in the rusted, broken-down Hunger City and named it Diamond Dogs.

Diamond Dogs features the icon working at the peak of his powers, both conceptually and musically; Hunger City is a loose enough narrative that it encompasses all of the songs on Diamond Dogs, but it still hangs together nicely, giving the album a pervasive sense of nihilistic dread and darkness that make the songs here — some of Bowie's best — intoxicating.

Bowie himself chose the "Sweet Thing/Candidate/Sweet Thing (Reprise)" suite as the second track to his self-curated iSelect compilation in 2008, and it remains some of his best, most dramatic songwriting to date. That suite sits alongside the dark disco of "1984," "Big Brother," which features the best bridge of Bowie's career (it's at 2:14) and fan favourite "Rebel Rebel," all of which easily make Diamond Dogs Bowie's most underrated record.

7. Station to Station

(1976)

Between the excellent Philadelphia soul-inspired Young Americans and his revered Berlin trilogy lies Station to Station, a six-song, slow-burning, coked-out masterpiece that harnesses both the jittery paranoia of Diamond Dogs and the soulful groove of its 1975 predecessor to summon the "return" of one of Bowie's most famous characters: the Thin White Duke.

The ten-minute opening title track is worth the price of admission alone. After over three minutes of train sounds, ominous piano plunks and swaggering rhythm, Bowie finally introduces himself: "The return of the Thin White Duke, throwing darts in lovers' eyes." Then, at 5:15, it all tumbles together into a disco epic that addresses cocaine and love before acknowledging that it's "too late to be grateful."

"Golden Years" and "TVC15" flex the funky muscle that defined Young Americans' best tracks, while ballads like "Word on a Wing" and standard "Wild is the Wind" give the album a crucial emotional heft. Station to Station is an elegant, groovy and sophisticated record that looks both backwards at the first half of Bowie's incredible 1970s and forward to the innovation of his next trilogy.

6. Scary Monsters

(1980)

After years of experimentation in Berlin with Brian Eno, Bowie returned to a more straightforward pop sound, but not without applying what he'd learned. The result was Scary Monsters, one of Bowie's most commercially successful records and an encapsulation of his '70s work that showed strains of glam and soul ("Fashion") alongside more dissonant ("It's No Game (Part 1)") and Eno-esque compositions ("Teenage Wildlife").

At the centre of it all is "Ashes to Ashes," a pop masterpiece that attained pop ubiquity without sacrificing an iota of weirdness, all while referring back to Major Tom, the hero of "Space Oddity" now turned junkie, in accordance with the turn of 1960s optimism into late '70s, post-Watergate pessimism.

Perhaps it's this sense of coming full circle, however darkly, that contributes to Scary Monsters' reputation as Bowie's last masterpiece, but there's a sense of purpose and cohesion here that even the excellent (but more hit-centric) Let's Dance can't touch. This is Bowie at his unique, beguiling best.

5. Blackstar

(2016)

We already loved Blackstar upon its release — I called it "a deeper, more affecting Bowie record" that embraces the past "while sounding unsure about the dark future"; Michael Rancic's prescient review called it a "defining statement from someone who isn't interested in living in the past, but rather, for the first time in a while, waiting for everyone else to catch up" — but in the context of Bowie's passing, it's hard not to consider it a masterpiece. This is a swan song in the truest sense of the term: Bowie wrote the album knowing he was about to die.

It's easy to hear in retrospect, especially on the title track, when he sings: "Something happened on the day he died/ Spirit rose a metre and stepped aside/ Somebody else took his place and bravely cried, 'I'm a black star/ I'm a black star.'" A black (dwarf) star is a star that's about to die, as it "no longer emits significant heat or light." In the video for "Blackstar," Bowie's wearing a blindfold. He sings about a "solitary candle." That context adds even more weight and significance to Blackstar, the first Bowie record in a long while that felt genuinely unhurried, at ease and self-assured.

It's a perfect, generous way for an artist like him to say goodbye. Rather than discuss what he was going through, Bowie turned his last few breaths of life into art. He knew he was leaving, so he created something of it, as he's always done, as he ever was compelled to. Because that is what creators do.

4. "Heroes"

(1977)

The second album in Bowie's Berlin trilogy is, depending on your mood, every bit as good as its predecessor, Low. The more emphatic record of the two, "Heroes" is as stark as its monochromatic cover art, especially in the juxtaposition between its sides: "Heroes" predicts the sound of Scary Monsters with its opening trio of muscly, riff-centric anthems, "Beauty and the Beast," "Joe the Lion" and the famous title track; on the record's ambient second side, "V-2 Schneider" is more upbeat, "Sense of Doubt" is more ominous and "Moss Garden" is more calming, respectively, than anything on Low.

This is all to establish just how good "Heroes" had to be; while a listener hearing Bowie's records in order of release might expect diminishing returns on the second of a trilogy, "Heroes" provides a deeper exploration of the song structures established on Low. It also boasts title track "Heroes," still one of Bowie's best and most iconic songs, and one that provided the "tasteful anthem" template for decades to come. Lest you find it cheesy, remember that the song was inspired by the idea of a couple living on either side of the divided Germany, forced to meet at the Berlin Wall; in 1977, when Bowie was living there, looking out his window at the wall every day, that meant risking death for love and freedom.

3. Hunky Dory

(1971)

In 1971, Hunky Dory formally announced Bowie's arrival as a genius after having hinted at the fact with Space Oddity and his heavier, more focused The Man Who Sold the World. Here, Bowie puts all his talents to work, in a scattered showcase of irrepressibly exuberant brilliance that can barely contain itself; Bowie jumps from style to style here seemingly just to show that he can.

And good lord, the songs: The elegant musical theatre bent of "Life on Mars" and "Oh! You Pretty Things" are remnants from Bowie's more music hall-influenced early style; "Andy Warhol" is a sparse, melodic tribute to the artist that showcases Bowie's playful side; "Queen Bitch" anticipates the glam rock of Bowie's next two albums so well that it nearly bests them; "Changes" remains the standard soundtrack to youth feeling that familiar, recurring sense of derision and disapproval from an older, established generation.

By this point, we're dealing with masterpieces only, and to rank them is nearly impossible — on any given day, Hunky Dory may be my favourite Bowie album. It's a collection of some of his best songs ever, but had yet to learn how to present them in a way that caught the world's imagination; a year later, he'd do exactly that.

2. Low

(1977)

After hitting rock bottom in Los Angeles, Bowie sought escape — both from his destructive cocaine habit and the isolation of that sprawling city — in Berlin, Germany. While there, Bowie met with ex-Roxy Music performer and producer Brian Eno to record a trilogy of albums (rounded out by "Heroes" and Lodger, though the latter was actually recorded in New York) that pushed far beyond the borders of what he'd recorded to date. Low was the surprising first of them, a record that, when it was delivered to RCA in mid-1976, seemed so out of left field that the label issued a best-of compilation (ChangesOneBowie) in its stead, before finally releasing the LP in January the following year.

On Low's first side, Bowie confronts his L.A. demons, singing about depression, loneliness and addiction in spiky, three-minute pop songs like "Breaking Glass," "Sound and Vision" and "Always Crashing in the Same Car." The second side was comprised of slow, ruminative instrumentals like "Warszawa," "Art Decade," "Weeping Wall" and "Subterraneans," all of which were marked by a sense of desperation, melancholy or both.

The sounds were arrived at with the aid of Eno's famous Oblique Strategies cards, which suggested, depending on the card, that the duo "Honor thy error as a hidden intention." The cards provided inspiration, and encouraged the duo to challenge and re-think their methods and modes as often as possible.

The result was an album that, to borrow a quote from modern composer Philip Glass, created "an art within the realm of popular music." The album resonated with artists across the UK, and reverberations of its influence are still felt today, whether in pop, ambient or drone music.

1. The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars

(1972)

At this point, there's not much left to write about Bowie's undeniable 1972 classic, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, and that made placing it at number one difficult.

As a hardcore Bowie fan, it felt too easy to call Bowie's most famous album his most essential, but then I realized that, hey: That instinct is bullshit. If someone asked me for the Bowie album to start with, I wouldn't play them my favourite Bowie record, Low, or Hunky Dory. I would give them The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars.

When I think of a Bowie record to put on, Ziggy doesn't occur to me; it's too ubiquitous, I think, or I tell myself I've heard it too many times. But then I hear those drums at the beginning of "Five Years," which build so slowly and perfectly; the crunchy, distorted opening chords and subdued acoustic verses of "Moonage Daydream"; the way the news bulletin-esque, single-note guitar wailing leads into the perfect, soaring chorus of "Starman." As much a collection of strong, standalone singles as a cohesive, narrative-based full-length statement, Ziggy Stardust not only put David Bowie on the road to stardom and helped establish glam-rock, but popularized the pop music alter ego that's been ubiquitous since.

The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars is a timeless album, and the perfect introduction to one of the century's most inventive and fascinating artists.

What to Avoid:

Bowie's first, self-titled 1967 record, for the now-defunct Deram, is a novel look at the young genius, but it's so hokey that when cheeky NME readers flooded the request phone line for his Sound + Vision tour to ensure he played that album's "The Laughing Gnome," he knew it was a joke and declined. His other early misstep, Pinups — perhaps the only inessential record he released in the 1970s — is neat for hardcore fans, but lacks the dynamism to entice more casual listeners.

It's a cliché that Bowie lost the plot in the 1980s, but it's hard to anticipate just how much until you actually listen to 1984's Tonight and 1987's Never Let Me Down, on which Bowie's first lacklustre songwriting efforts also suffer from tinny production and some of his most cringe-worthy style crossover experiments (blue-eyed pop-reggae, anyone?).

In retrospect, it's apparent that Tin Machine, the anachronistic rock'n'roll band Bowie founded at the end of the '80s, was a smart and necessary move, but their two records still haven't aged very well. The first is worth a listen, but Tin Machine II is utterly skippable, and neither are particularly crucial to understanding Bowie better. His return to solo fare, 1993's Black Tie White Noise, features slightly better songwriting, but it's only marginally better than his two '80s solo blunders, despite being seen as a return to form (he'd do so two years later, on 1. Outside).

Bowie spent most of the next decade re-finding his adventurous, more sure-footed musical self, putting out a series of albums that ranged from good to great until 2003, when he released his last record for a decade. His 2013 return, The Next Day, was a much welcomed one, and it has some stunning moments — "The Stars (Are Out Tonight)" and "Where Are We Now?" particularly — but in the grand scheme of things, it doesn't offer much that, say, 1999's 'hours…' doesn't.

Further Listening:

Basically any David Bowie album not yet mentioned is worth investigating — 1973's Aladdin Sane is an excellent, even glammier Ziggy Stardust exercise; 1983's Let's Dance is Bowie at his brash pop star best, especially on "Modern Love" and "Cat People (Putting Out Fire)"; the oft-maligned Earthling finds Bowie fully embracing drum & bass, and while some accuse it of dilettantism, close listening to the songwriting reveals some of Bowie's most formidable work — but there are a few that stand out even more strongly.

The Man Who Sold the World (1971) is the formative bridge between Space Oddity and Hunky Dory, and finds Bowie tackling some of his most poignant subject matter, as he explores war, religion and mental illness across bluesy and hard-rocking instrumentals. Young Americans, his 1975 foray into Philadelphia soul, is just as essential; the record provides the funk and soul context for the latter half of his 1970s work, and the joyous title track is one of Bowie's best-ever songs.

1979's Lodger is the most overlooked record of Bowie's Berlin trilogy (though it was actually recorded in the U.S.), and though it's a little different — there's no instrumental second side, for example — it's an incredible record that harnesses the sound of those Eno sessions for more a straightforward, worldly set of songs. The Berlin sound would also permeate Bowie's 1993 soundtrack to the BBC's four-part TV serial The Buddha of Suburbia, a lost gem that features gorgeous ambient pieces ("Sex and the Church," "The Mysteries"), as well as a number of more traditional pop songs ("Strangers When We Meet") that blow that year's Black Tie White Noise out of the water.

1999's 'hours…', 2002's Heathen and 2003's Reality weren't beloved upon their release (except maybe the stately Heathen), but in the decade since, they've aged well, as they showcase more mature songwriting and fewer production tricks. These records are pure neo-classicist Bowie, and while they're not quite essential, they're satisfying listens.

Critics have tended to be hard on Bowie's live albums, but for those interested, the bootleg-turned-official release Live Santa Monica '72 is perhaps the best, as it captures a young, energized Bowie with something to prove in the wake of his struggle to find success up until Ziggy Stardust. 1974's David Live is a glammy, post-Diamonds Dogs affair, and 1978's fascinating Stage, released in the midst of his Berlin phase, finds the musician attempting to weave his more experimental material in with his early '70s classics.