After a fire in 2017 destroyed almost everything his family owned, Elephant Stone's Rishi Dhir got to thinking: "When you lose everything, what do you do? How do you react? How do you deal with it and how do you deal with the people around you?" It inspired Hollow, a narrative album that follows the global elite leaving a dead Earth for Planet B, which turns out to be equally inhospitable to life. "They build religion, then destroy religion, then turn on each other and the cycle repeats."

Dhir wrote, recorded and engineered the album in his home studio, "the warmest room" in his family's house in Montreal's la Petite-Patrie neighbourhood, where a drum kit perches in one corner and guitars and basses hang from the low white walls. Two sitars stand by the door like just-arrived relatives.

Having a home studio is new for Dhir. It means no drums after 8 p.m. because he is located just under his two boys' bedroom; it also means easy access to ten-year-old Meera, who sings on three songs, including lead single "Hollow World." (A true star, when her father tells her she's "always on the radio," that "like 200,000 people heard you sing," she shrugs.) "At bedtime the boys would go to bed and she'd come down for an hour-and-a-half and we'd just record."

Most of the time though, "[The kids] know they're not allowed to come in," and this is Dhir's space to tinker alone. Every morning, while passing through the garage to get to work, he picks up a guitar or plays the drums for 30 minutes. He hunkers down each night while his wife Kirsty reads to the kids. "I try to create melodies every day."

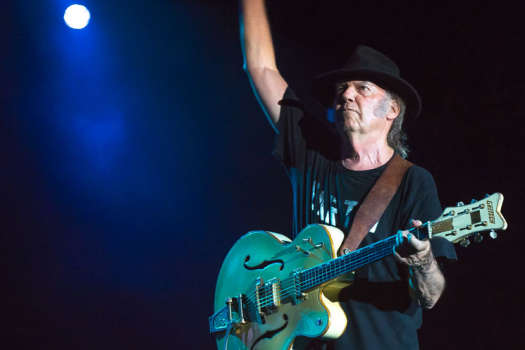

Hollow has the most sitar of any previous Elephant Stone album, he says, but "it's less of a centrepiece now, and more just part of the sonic palette." One song, "Land of the Dead," was written on the sitar, so "we ended up going more metal with it." Having his own space means "I can do stuff like that now, just see where it goes, spend hours on one sound." He can work on his drumming, give his children sitar lessons, and even use the space as a makeshift guestroom for travelling musician friends. He recently tried mixing some songs for friend and musician Krista Muir, who babysat his kids in return, and also bought analogue compressors and a ribbon mic "just to get new sounds."

Dhir says he's learned more while working on this album than he has in his past 25 years of making music. "It used to just be like magic, like 'How did the engineer do that?' And now I know." Still, there remains "a lot of magic and mysterious stuff that you can't recreate." He especially likes playing with his Space Echo, because "it's analogue and I like how everything's unpredictable." He describes making Hollow as a "series of mistakes." "I'm like, 'How did we do that?' I'm like, 'I don't know, but we did it. Let's just keep it.'"

One unmistakable certainty: the sound of his studio. "When the album was done, I was like, 'This is what the room sounds like.'" It's a dead room, which makes for dry drums, especially because he baffles them and builds a wall when he plays. The room's particular acoustics were actually perfected by chance, when Dhir happened to move his desk to listen to an album with a friend. If not for that, "if this room sounded like shit, it wouldn't be inspiring."

In spite of being "not jaded, exactly" and the implications of Hollow's narrative, the studio's origin story insists on veering toward what some research suggests, which is that people actually tend to cooperate in times of crisis. "A lot of people built this room," he says of the studio, including fellow band member and carpenter Thor Harris and Dhir's brother-in-law. "It brought people together."

Dhir wrote, recorded and engineered the album in his home studio, "the warmest room" in his family's house in Montreal's la Petite-Patrie neighbourhood, where a drum kit perches in one corner and guitars and basses hang from the low white walls. Two sitars stand by the door like just-arrived relatives.

Having a home studio is new for Dhir. It means no drums after 8 p.m. because he is located just under his two boys' bedroom; it also means easy access to ten-year-old Meera, who sings on three songs, including lead single "Hollow World." (A true star, when her father tells her she's "always on the radio," that "like 200,000 people heard you sing," she shrugs.) "At bedtime the boys would go to bed and she'd come down for an hour-and-a-half and we'd just record."

Most of the time though, "[The kids] know they're not allowed to come in," and this is Dhir's space to tinker alone. Every morning, while passing through the garage to get to work, he picks up a guitar or plays the drums for 30 minutes. He hunkers down each night while his wife Kirsty reads to the kids. "I try to create melodies every day."

Hollow has the most sitar of any previous Elephant Stone album, he says, but "it's less of a centrepiece now, and more just part of the sonic palette." One song, "Land of the Dead," was written on the sitar, so "we ended up going more metal with it." Having his own space means "I can do stuff like that now, just see where it goes, spend hours on one sound." He can work on his drumming, give his children sitar lessons, and even use the space as a makeshift guestroom for travelling musician friends. He recently tried mixing some songs for friend and musician Krista Muir, who babysat his kids in return, and also bought analogue compressors and a ribbon mic "just to get new sounds."

Dhir says he's learned more while working on this album than he has in his past 25 years of making music. "It used to just be like magic, like 'How did the engineer do that?' And now I know." Still, there remains "a lot of magic and mysterious stuff that you can't recreate." He especially likes playing with his Space Echo, because "it's analogue and I like how everything's unpredictable." He describes making Hollow as a "series of mistakes." "I'm like, 'How did we do that?' I'm like, 'I don't know, but we did it. Let's just keep it.'"

One unmistakable certainty: the sound of his studio. "When the album was done, I was like, 'This is what the room sounds like.'" It's a dead room, which makes for dry drums, especially because he baffles them and builds a wall when he plays. The room's particular acoustics were actually perfected by chance, when Dhir happened to move his desk to listen to an album with a friend. If not for that, "if this room sounded like shit, it wouldn't be inspiring."

In spite of being "not jaded, exactly" and the implications of Hollow's narrative, the studio's origin story insists on veering toward what some research suggests, which is that people actually tend to cooperate in times of crisis. "A lot of people built this room," he says of the studio, including fellow band member and carpenter Thor Harris and Dhir's brother-in-law. "It brought people together."