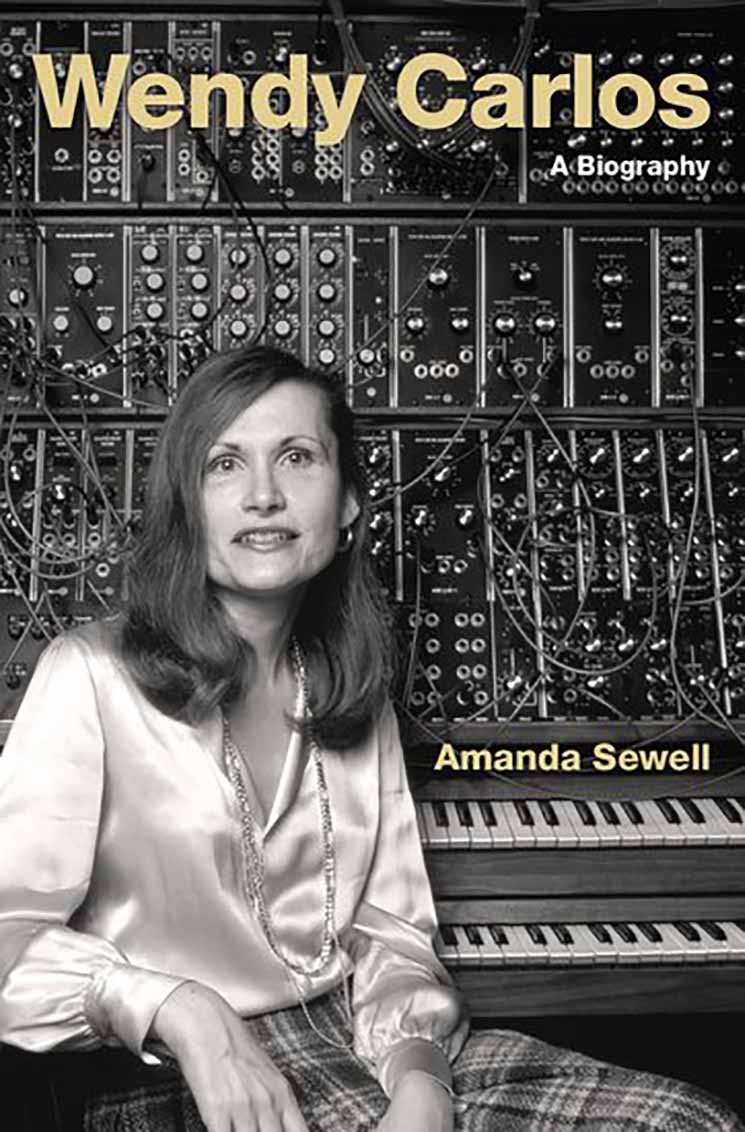

Electronic music fans with a particular interest in audio engineering are likely familiar with the name Wendy Carlos. Film buffs with a predilection for soundtracks may be as well (she scored Stanley Kubrick's The Shining and A Clockwork Orange, as well as the original 1982 TRON). Or perhaps your cool audiophile uncle or musicology professor has proudly proffered an original pressing of her breakthrough Switched-On Bach from 1968, urging you to handle it with care.

Wherever you fall, your appreciation for Carlos's pioneering synthesizer and production work will surely be enhanced by Amanda Sewell's excellent biography.

A brilliant and trailblazing artist, Carlos herself is fascinating enough, but it's the intersection of her life with other historical currents that makes Sewell's account especially compelling. Inspired as a child by French musique concréte composer Pierre Henry, Carlos was on the ground floor of experimental electronic music during the late '60s, basically making Bob Moog's career along the way with Switched-On Bach (a collection of the Baroque composer's work rendered entirely with Moog's synthesizer modules), and Sewell's book offers a fascinating glimpse into the world of post-war technology, musical and otherwise. Oscillators seem to be everywhere.

Carlos was also one of the first public figures in the U.S. to acknowledge her gender transition (she was named Walter at birth and assigned male), and Sewell's survey of the social and medical landscape of the time as it relates to the transgender experience is both timely and informative, as well as sad. What emerges is a portrait of a driven and persevering (although sometimes difficult and certainly opinionated) artist whose work was very much ahead of its time, a perfectionist whose self-proclaimed "First Law" was that "any parameter you can control, you must control."

The impact of Switched-On Bach at the time of its release must be made clear — it broke every classical music sales record in history, became the best-selling classical album of all time, and in 1969 was the 21st best-selling album in any genre. Glenn Gould hailed it as the album of the decade. The general public hadn't heard a synthesizer make anything but sound effects up to this point, and the marriage of this brand new technology with the tried and true content of a "great composer" was an instant sensation. The immense success of the album caught everyone by surprise, including Carlos, who had been transitioning to female socially for many years at this point, and who was now catapulted into the spotlight — as "Walter."

This combination of circumstances was paralyzing, and fearing for her career, as well as safety (there were no anti-discriminatory laws for someone in her position at the time), Carlos retreated from public view (although she continued to release music) and didn't disclose her transition until 1979. The details of this decade of socially imposed exile are often heartbreaking: Sewell includes an account of how Stevie Wonder once knocked on Carlos's door, eager to see "Walter's" home studio (likely one of the most cutting-edge in the country); Carlos let him knock until he left.

An antidote to these sadder moments are the amusing glimpses Sewell provides of Carlos's lively, sharp-tongued and frankly often cantankerous personality. Thoroughly convinced of the importance of electronic composition for the future of music, she nonetheless railed against what she saw as the inadequacy of current synthesizers to get her there (a close friend of Bob Moog's throughout her life, she still criticized his products endlessly in various interviews and letters), and a late-career interest in microtonal and alternate tunings saw her aghast at how few of her contemporaries followed her into this brave new world.

Unfortunately, things are a bit bleak for anyone interested in Carlos's music in 2020, as one new world she has yet to brave is that of digital distribution, suspicious perhaps of the decidedly uncontrollable world of the internet. None of her music is available for purchase or streaming online, and physical copies have been out of print for close to a decade (Carlos reacquired the rights to her catalogue in 2009 and has chosen not to reissue anything since). She also chose not to participate in Sewell's biography in any way. The only way you're guaranteed to hear from her today is if you post her music on YouTube in any form, as her legal team issues DMCAs with alacrity. That's control all right, but to what end remains unknown.

(Oxford University Press)Wherever you fall, your appreciation for Carlos's pioneering synthesizer and production work will surely be enhanced by Amanda Sewell's excellent biography.

A brilliant and trailblazing artist, Carlos herself is fascinating enough, but it's the intersection of her life with other historical currents that makes Sewell's account especially compelling. Inspired as a child by French musique concréte composer Pierre Henry, Carlos was on the ground floor of experimental electronic music during the late '60s, basically making Bob Moog's career along the way with Switched-On Bach (a collection of the Baroque composer's work rendered entirely with Moog's synthesizer modules), and Sewell's book offers a fascinating glimpse into the world of post-war technology, musical and otherwise. Oscillators seem to be everywhere.

Carlos was also one of the first public figures in the U.S. to acknowledge her gender transition (she was named Walter at birth and assigned male), and Sewell's survey of the social and medical landscape of the time as it relates to the transgender experience is both timely and informative, as well as sad. What emerges is a portrait of a driven and persevering (although sometimes difficult and certainly opinionated) artist whose work was very much ahead of its time, a perfectionist whose self-proclaimed "First Law" was that "any parameter you can control, you must control."

The impact of Switched-On Bach at the time of its release must be made clear — it broke every classical music sales record in history, became the best-selling classical album of all time, and in 1969 was the 21st best-selling album in any genre. Glenn Gould hailed it as the album of the decade. The general public hadn't heard a synthesizer make anything but sound effects up to this point, and the marriage of this brand new technology with the tried and true content of a "great composer" was an instant sensation. The immense success of the album caught everyone by surprise, including Carlos, who had been transitioning to female socially for many years at this point, and who was now catapulted into the spotlight — as "Walter."

This combination of circumstances was paralyzing, and fearing for her career, as well as safety (there were no anti-discriminatory laws for someone in her position at the time), Carlos retreated from public view (although she continued to release music) and didn't disclose her transition until 1979. The details of this decade of socially imposed exile are often heartbreaking: Sewell includes an account of how Stevie Wonder once knocked on Carlos's door, eager to see "Walter's" home studio (likely one of the most cutting-edge in the country); Carlos let him knock until he left.

An antidote to these sadder moments are the amusing glimpses Sewell provides of Carlos's lively, sharp-tongued and frankly often cantankerous personality. Thoroughly convinced of the importance of electronic composition for the future of music, she nonetheless railed against what she saw as the inadequacy of current synthesizers to get her there (a close friend of Bob Moog's throughout her life, she still criticized his products endlessly in various interviews and letters), and a late-career interest in microtonal and alternate tunings saw her aghast at how few of her contemporaries followed her into this brave new world.

Unfortunately, things are a bit bleak for anyone interested in Carlos's music in 2020, as one new world she has yet to brave is that of digital distribution, suspicious perhaps of the decidedly uncontrollable world of the internet. None of her music is available for purchase or streaming online, and physical copies have been out of print for close to a decade (Carlos reacquired the rights to her catalogue in 2009 and has chosen not to reissue anything since). She also chose not to participate in Sewell's biography in any way. The only way you're guaranteed to hear from her today is if you post her music on YouTube in any form, as her legal team issues DMCAs with alacrity. That's control all right, but to what end remains unknown.