Sure, I'll say it. The most influential non-hip-hop record of the early '90s was Uncle Tupelo's No Depression, and I'll stand on Kurt Cobain's grave and scream it.

I loved Nevermind when I first heard it. I still like it a lot. It was (and remains) a terrific record. And it no doubt spawned a generation of "alternative" rock'n'rollers. But almost 25 years on, there is very little consensus as to what exactly constitutes "alternative rock" as invented (and/or popularized) by Nirvana. Their freshness had a lot to do with their undeniable talent for writing and playing hard-driving melodic music, but it probably had more to do with the relative inertia of radio rock'n'roll at that moment. Nirvana, along with Pearl Jam and Alice in Chains and Smashing Pumpkins et al., revitalized a mainstream genre that had fallen into predictable patterns.

Despite the rather immediate canonization of Cobain and the bronzing of Nevermind (both of which I support), I remain unconvinced that this record has had the widest influence on the sound of things that followed. While rock radio was changed dramatically in its wake, and the way rock'n'roll songs are produced (with the concept of the whisper-to-scream now firmly entrenched) is attributable to the sound of that record, as we sit here amid what feel like the shards and dregs of mainstream rock'n'roll, Nevermind starts looking more and more like the last gasp of a fading genre.

Maybe not, of course. I'm not really here to prognosticate. But, I am here to report that today's thriving alternative country genre (however you'd like to define it) is, in a radical sense, born of Uncle Tupelo's first record. You can draw direct lines from here to there.

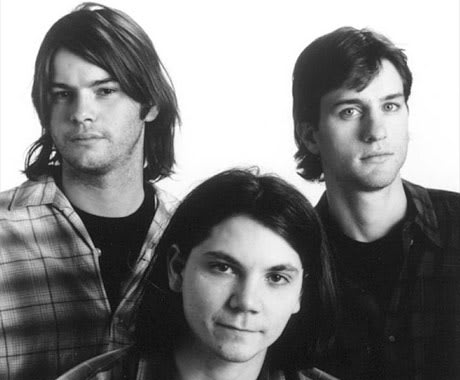

Recorded for $3,500 over ten days at the very beginning of 1990, No Depression was released in June on the independent Rockville label. By the end of the year, it had sold 15,000 copies — quite a feat for an independent record — and had already become something of a shibboleth for folks interested in new directions in popular music. Here was a (mostly) three-piece act that played country music like punks, or punk like country music. This innovative hybridity, this audacious mashing of two apparently unlikely genres together, was as shocking as it was compelling. If it had been merely OK, it could have been dismissed as a stunt. But it worked. It worked pretty goddamn well.

I asked Uncle Tupelo's drummer Mike Heidorn to explain these connections to me: "The volume of music we were listening to in those years [was huge]! We were buying vinyl records and as a band we were listening to '60s garage bands like the Chocolate Watchband, the Sonics, the Standells, the Remains and the Turtles, all that stuff. And our older brothers and friends would come back from college with all this new music, and that meant the Ramones, the Lords of the New Church, Elvis Costello, the Jam, Gang of Four. And that's what came of it. The history of all of this music before us that we had just soaked in, all this British punk and American garage rock."

It didn't hurt that Uncle Tupelo featured two immensely talented singer-songwriters in Jeff Tweedy (who was the junior partner at this early stage, but was showing flashes of brilliance) and Jay Farrar. In his early 20s, Farrar had arrived fully formed, possessed of a voice so absurdly commanding and richly textured, few could believe it emerged from such a young man. And his songwriting — wise, even profound, Farrar sounded every bit like the sage he would eventually (irritatingly) style himself to be.

"Old enough to know better but young enough to not really care what all instruments we brought along to our demo sessions!" is how Heidorn describes their approach. "I remember it was in Champagne, IL at Matt Allison's attic studio. We couldn't have put another instrument into the van [we rode down there]. Every electric guitar we had. A bass, a banjo, fiddles. We just grabbed all the instruments we could. Didn't think about 'Should a banjo be on the same album as all these distortion pedals?' We just combined them. And of course we found the flange button and we brought a cowbell. Through naiveté we didn't set ourselves any limits on which instruments to use. We brought 'em all."

But what, I ask, about the country influences? Where did they fit into the mix? "I didn't know many country songs," Heidorn admits, "and in my house we didn't really hear much of that. I always gravitated toward the '60s garage bands. But I think, really, the country thing just came out of Jay's vocals. Jay's seasoned voice. And we had these acoustic guitars, banjos, fiddles, a harmonica, and when they got combined with Jay's voice… He and Jeff I think understood the Ozarks and rural Missouri a little more than me. They had family functions there with acoustic country sing-alongs. I just didn't have that element. I just basically followed Jay and Jeff's intuition. That's the thing that makes the difference from all the records that came before: there wasn't much country in the Ramones or the Lords of the New Church!"

Indeed. This was the thing. Uncle Tupelo played country music (with all of its sentimentality, back porch wisdom, tendency towards character studies, concern for the working man, struggles with and/or adherence to religion and tradition) smashed up against the incendiary power of garage rocking punk music.

Obviously stuff in this general territory this had been tried before. The crossovers between rock'n'roll and country, and even punk and country, were legion by 1990, from the Beatles to the Byrds to the Rolling Stones to Linda Ronstadt to Elvis Costello to the Knitters (the country band offshoot of Los Angeles' X) to Lucinda Williams. But in order to find the sound of Uncle Tupelo, you'd have to take each of these influences and throw them into a blender with the Nuggets compilations, the Clash, Hüsker Dü, the Replacements, and the Carter Family. Because Uncle Tupelo simply sounded nothing like anything that came before them. Not really.

But, after them? Leaving aside the broad influence their respective post-Tupelo careers have enjoyed (Farrar founded Son Volt, Tweedy founded Wilco), it is almost impossible to think of an alt-country band that has emerged in their wake that doesn't owe something fundamental to this band, to this record. You name an artist, this album mattered to them.

Thankfully, Sony Legacy has chosen to compile and release a double-CD edition of No Depression so you can hear all of this for yourself in finely re-mastered glory. The collection includes the original record (still, to my ears, very nearly perfect), several outtakes, a few live cuts, and (most exciting of all) the original demo tape Not Forever Just For Now that got them signed in the first place. This is a boon for fans, of course, but the collection will also be of interest to new recruits looking to hear the foundational text of their favourite genre. For alt-country fans, this is the very definition of an indispensable release.

I loved Nevermind when I first heard it. I still like it a lot. It was (and remains) a terrific record. And it no doubt spawned a generation of "alternative" rock'n'rollers. But almost 25 years on, there is very little consensus as to what exactly constitutes "alternative rock" as invented (and/or popularized) by Nirvana. Their freshness had a lot to do with their undeniable talent for writing and playing hard-driving melodic music, but it probably had more to do with the relative inertia of radio rock'n'roll at that moment. Nirvana, along with Pearl Jam and Alice in Chains and Smashing Pumpkins et al., revitalized a mainstream genre that had fallen into predictable patterns.

Despite the rather immediate canonization of Cobain and the bronzing of Nevermind (both of which I support), I remain unconvinced that this record has had the widest influence on the sound of things that followed. While rock radio was changed dramatically in its wake, and the way rock'n'roll songs are produced (with the concept of the whisper-to-scream now firmly entrenched) is attributable to the sound of that record, as we sit here amid what feel like the shards and dregs of mainstream rock'n'roll, Nevermind starts looking more and more like the last gasp of a fading genre.

Maybe not, of course. I'm not really here to prognosticate. But, I am here to report that today's thriving alternative country genre (however you'd like to define it) is, in a radical sense, born of Uncle Tupelo's first record. You can draw direct lines from here to there.

Recorded for $3,500 over ten days at the very beginning of 1990, No Depression was released in June on the independent Rockville label. By the end of the year, it had sold 15,000 copies — quite a feat for an independent record — and had already become something of a shibboleth for folks interested in new directions in popular music. Here was a (mostly) three-piece act that played country music like punks, or punk like country music. This innovative hybridity, this audacious mashing of two apparently unlikely genres together, was as shocking as it was compelling. If it had been merely OK, it could have been dismissed as a stunt. But it worked. It worked pretty goddamn well.

I asked Uncle Tupelo's drummer Mike Heidorn to explain these connections to me: "The volume of music we were listening to in those years [was huge]! We were buying vinyl records and as a band we were listening to '60s garage bands like the Chocolate Watchband, the Sonics, the Standells, the Remains and the Turtles, all that stuff. And our older brothers and friends would come back from college with all this new music, and that meant the Ramones, the Lords of the New Church, Elvis Costello, the Jam, Gang of Four. And that's what came of it. The history of all of this music before us that we had just soaked in, all this British punk and American garage rock."

It didn't hurt that Uncle Tupelo featured two immensely talented singer-songwriters in Jeff Tweedy (who was the junior partner at this early stage, but was showing flashes of brilliance) and Jay Farrar. In his early 20s, Farrar had arrived fully formed, possessed of a voice so absurdly commanding and richly textured, few could believe it emerged from such a young man. And his songwriting — wise, even profound, Farrar sounded every bit like the sage he would eventually (irritatingly) style himself to be.

"Old enough to know better but young enough to not really care what all instruments we brought along to our demo sessions!" is how Heidorn describes their approach. "I remember it was in Champagne, IL at Matt Allison's attic studio. We couldn't have put another instrument into the van [we rode down there]. Every electric guitar we had. A bass, a banjo, fiddles. We just grabbed all the instruments we could. Didn't think about 'Should a banjo be on the same album as all these distortion pedals?' We just combined them. And of course we found the flange button and we brought a cowbell. Through naiveté we didn't set ourselves any limits on which instruments to use. We brought 'em all."

But what, I ask, about the country influences? Where did they fit into the mix? "I didn't know many country songs," Heidorn admits, "and in my house we didn't really hear much of that. I always gravitated toward the '60s garage bands. But I think, really, the country thing just came out of Jay's vocals. Jay's seasoned voice. And we had these acoustic guitars, banjos, fiddles, a harmonica, and when they got combined with Jay's voice… He and Jeff I think understood the Ozarks and rural Missouri a little more than me. They had family functions there with acoustic country sing-alongs. I just didn't have that element. I just basically followed Jay and Jeff's intuition. That's the thing that makes the difference from all the records that came before: there wasn't much country in the Ramones or the Lords of the New Church!"

Indeed. This was the thing. Uncle Tupelo played country music (with all of its sentimentality, back porch wisdom, tendency towards character studies, concern for the working man, struggles with and/or adherence to religion and tradition) smashed up against the incendiary power of garage rocking punk music.

Obviously stuff in this general territory this had been tried before. The crossovers between rock'n'roll and country, and even punk and country, were legion by 1990, from the Beatles to the Byrds to the Rolling Stones to Linda Ronstadt to Elvis Costello to the Knitters (the country band offshoot of Los Angeles' X) to Lucinda Williams. But in order to find the sound of Uncle Tupelo, you'd have to take each of these influences and throw them into a blender with the Nuggets compilations, the Clash, Hüsker Dü, the Replacements, and the Carter Family. Because Uncle Tupelo simply sounded nothing like anything that came before them. Not really.

But, after them? Leaving aside the broad influence their respective post-Tupelo careers have enjoyed (Farrar founded Son Volt, Tweedy founded Wilco), it is almost impossible to think of an alt-country band that has emerged in their wake that doesn't owe something fundamental to this band, to this record. You name an artist, this album mattered to them.

Thankfully, Sony Legacy has chosen to compile and release a double-CD edition of No Depression so you can hear all of this for yourself in finely re-mastered glory. The collection includes the original record (still, to my ears, very nearly perfect), several outtakes, a few live cuts, and (most exciting of all) the original demo tape Not Forever Just For Now that got them signed in the first place. This is a boon for fans, of course, but the collection will also be of interest to new recruits looking to hear the foundational text of their favourite genre. For alt-country fans, this is the very definition of an indispensable release.