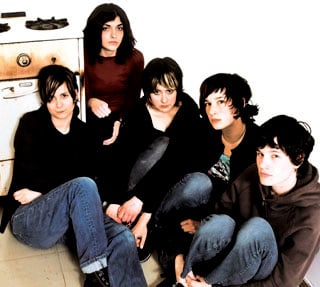

Last time I saw the Organ play, I was among the few hundred Montrealers who'd converged for the BC band's first crack at Quebec. Androgynous college girls, highly stylised 20-somethings and a few greying folks in faded Smiths T-shirts turned out on the strength of some impassioned praise online and in print, all alongside five pretty pictures of women in uniform. Superseding all the promotion and the hype, however, were the six indelible songs on the Organ's debut EP.

In 2002, Sinking Hearts introduced a band that evoked the minor chord melancholy of the early '80s, some songs achieving that irresistible fusion of dour poetry and danceable tunes. Whether it was simply nostalgia, the charm of audibly amateurish musicians with such a distinctive vision and style, or the allure of a female band with unisex appeal, these girls swiftly made away with hearts and minds across the continent, and with the recent release of their exceptional LP, Grab That Gun, it appears we've all made a sound investment.

Visiting Vancouver for the first time in a decade, I arranged a rendezvous with the Organ on my second night in city. From a street corner in downtown's east side, we make our way to Honey, an ornate lounge-pub only steps away from the band's rehearsal space. Singer Katie Sketch is instantly talkative, though she rarely makes eye contact and occasionally cradles her face in her hands. The Organ have a rep for lacking confidence, petrified at the sight of the ever-expanding crowds that flock to their shows, and subsequently seeming detached on stage, a trait some mistake for either drop-dead cool or "snobby." They have a tendency to be overly modest, but it's hard to argue with the girls when they say they're hardly virtuoso musicians.

Katie Sketch is the exception. Having studied violin from the age of three, competitive skiing in her pubescent years, studio engineering in her late teens and, currently, psychology at SFU, it's clear that the rich croon and discreet charisma she displays on stage are grounded in discipline.

The classically-trained multi-instrumentalist certainly put her skills to use throughout the three years it took to get the Organ together. Organist Jenny Smyth, the youngest (22) and bubbliest of the bunch, entered the picture when she joined Sketch's instrumental trio, Full Sketch. After that band dissolved, the duo branched off to audition players for their new band, a gruelling process that finally culled self-taught guitarist Debora Cohen. Cohen is conspicuously silent throughout the interview, uttering only five words at the tail end of a crude tour story: "I slept in cat piss."

"Deb, this is getting so boring with you talking so much!" gibes Sketch, who more than makes up for her band-mate's silence. Sitting on either side of Cohen are drummer Shelby Stocks, at 28 the eldest and possibly wisest of the gang, and bassist Ashley Webber, a friendly girl with a funny bleak streak. The rhythm section joined the band late in the game, after Sketch abandoned auditions and decided to simply hire like-minded people and teach them how to play.

"It's not like the five of us got together and spontaneously created this," Sketch explains. "Jenny and I had a direction we wanted to go in and then we slowly recruited people. We could tell if someone didn't get it, which is why we had to get rid of so many players. It's funny sometimes people say the band's moving really quickly, but I feel like I've been doing this forever."

Five years is a long time, long enough for this band to assemble the right crew, develop their craft, tour the continent, record 13 songs and sign to three labels first Global Symphonic, then 604 and Mint. In the public eye, the Organ is a new band, but its members say they've matured significantly since its formation, both as people (Smyth: "I was a child!"; Webber: "I was a goth!"), and as musicians.

"Last year was all about practicing and getting better," says Sketch. "Now I feel like we're actually musicians we're really tight, and proud of what we do."

Heaven Knows I'm Miserable Now

Heaven Knows I'm Miserable Now

Throughout the interview, Honey's sound system blares a hot mix of '70s and '80s classics, everything from Frankie Goes to Hollywood to the Ramones to Lene Lovich to the Information Society. Smyth's Hammond 123XL "Romance Series" organ and her '60s rock'n'soul-influenced playing hardly qualify as the stuff of synth-pop (though she jokes that her other band, the Ewoks, "pioneered electroclash"), and they don't bow low enough before the Velvet Underground and Gang of Four to resemble New York's more raucous retro fad. Nevertheless, the Organ are often grouped with a general revivalist trend, sometimes loosely termed "new new wave." (Ten years ago, UK bands like Elastica and Supergrass were allegedly "the new wave of the new wave," but I digress.)

"New wave is a haircut," says Sketch, as confused as anyone about the meaning of the term. "We're too dark and moody for that."

Regardless, new wave's grand dames Debbie Harry, Siouxsie Sioux and Alison Moyet often pop up in reference to Sketch's vocals, while the Smiths, the Cure and Joy Division form the grand triad of elder boy bands that the Organ is always compared to. Along with the similarly downcast and lo-fi aesthetic, it's hard to miss the echo of Robert Smith and Johnny Marr in Cohen's guitar and the assertive Peter Hook-isms in Webber's bass lines.

Eloquently illustrating cold, pain, darkness, despair, loneliness, longing, self-mutilation and suicide, Sketch's lyrics also reflect her musical influences, as well as the band's collective history of clinical depression and severe social alienation.

"I listen to a lot of music with happy lyrics, but when I try writing a lighter song, it always sounds faux," Sketch says. "And if I'm in a good headspace, I'm not sitting at home writing, I'm doing something with friends or drinking at a bar. I've tried writing lyrics at 3 p.m. at the beach, but it always works better late at night, when I'm feeling manic about something."

Not surprisingly, the girls have a wealth of morbid thoughts in mind. They're all anxious about the following day's trip to Toronto, partly due to their press and promo obligations, mostly due to the flight itself. Only the previous day, NORAD fighter jets had been summoned to "escort" an Air Canada plane into Vancouver because of some bogus terrorist threat, so Webber and Smyth sporadically wallow in morbid talk about hijackers, crashes and violent turbulence, turning Cohen's olive complexion pale. In maternal mode, Stocks elbows in with a pointed shush: "No more death talk!"

Along with the depressive nature of their lyrics and their banter, the double entendres of their name and their album title would have made an Organ fan out of Freud. If that weren't enough, Sketch uttered this excellent slip about Grab That Gun: "Whenever I mention the title, I get an ere- a reaction," she says, as her band-mates stifle laughter.

But Sketch has a sense of humour too, notably regarding the full frontal Morrissey thread that runs through her singing. Grab That Gun's main attraction for sway-heads is a song that dates back to Full Sketch: "Steven Smith," a not-so-covert tribute to Steven Patrick Morrissey. Its recently-penned lyrics, Sketch's darkest to date, aren't literally about the ex-Smith, but they are the source of the Organ's LP title.

In an amusing coincidence, the cover of Morrissey's new album, You Are the Quarry (released a week before Grab That Gun) is a gangster-chic photo of the Mozzer clutching a Tommy gun. This little factoid elicits a loud flurry of responses from the band: "Fuck off!" "Oh my God, no!" "That's hilarious!" "That's brutal or is it good? I can't tell."

Jumping Someone Else's Train

Apart from a touch of guitar ring and vocal reverb, the Organ's early songs were bell- and whistle-free, lo-fi recordings lacking that homogenised coating that dulls so much mainstream music. Though their minimal arrangements and unpolished playing leave the band vulnerable to criticism, those qualities are clearly part of what makes the Organ so endearing.

"I like the flaws and the edgy sound that we have," says Stocks, "it's a nice, refreshing, real thing." Unfortunately, the real thing was lost on the original version of Grab That Gun, produced by the band's friend Kurt Dahle of the New Pornographers. It's an uneasy discussion, as the girls don't want to hurt feelings or create friction, but they describe Dahle's record as mechanical, clean and perfect.

"We're so not about perfection," says Stocks. "But Kurt was only trying to do what he thought was best for us. He wanted to take us in a bigger direction than we were willing to put ourselves out for, 'cause we're not those kind of girls."

"No, we're not," Sketch concurs. "It was a different kind of success. It felt like those mixes would suit us if we all decided to wear crop-tops and get total makeovers, and maybe some plastic surgery in this area," she adds, hoisting her mammaries. "It just did not make me feel comfortable."

Making matters more awkward, the New Pornographers and the Organ toured the U.S. together almost immediately after the girls heard what Dahle had to offer.

"It was really hard for us not to bring it up on tour, because it felt like we were whispering behind his back," Stocks explains. "In retrospect, I guess we were, but we just didn't want to get into bad vibes."

"When we got back, the record was literally mixed and going to mastering when we had a fit," says Sketch. "Stop! Wait, wait, wait we're not putting this out.'"

Apart from the effect it might have on their friendship with Dahle, what made this a particularly difficult decision was the mounting pressure the band was facing from everyone who expected the album to drop last fall.

"People I really trust kept telling me, It's taking way too long, you have to put the album out now or everybody's gonna forget about you,'" says Smyth.

"We didn't fucking care," adds Stocks, "we had to put something out that we were all gonna stand by."

Salvaging only a few bass and drum tracks, the band re-recorded the entire album, this time with their own gear. It was engineered by Paul Forgues, mixed by Todd Simko and overseen by Sketch, who eagerly applied her engineering expertise.

"I was very, very, very, very involved," she says. "We couldn't afford, mentally, physically or financially, to have any more mistakes."

"We looked forward to putting out something great with Kurt, and a lot of work went into it, but there's no hate it's just too bad," says Stocks. There's also consensus among the girls that they wouldn't have been ready to release and promote the album as far back as last fall.

"We weren't mature enough then," says Smyth. "Now, we can handle our shit." Addressing her band-mates, she asks "can you imagine if we were putting this record out when I was having that nervous breakdown?!"

After a round of laughter, Stocks pipes in with, "Yeah, that would have been a nightmare. Anyway, the album we've got is something we're really happy with, so it was all worth it."

Memorize the City

Memorize the City

When Honey's friendly waiter comes around with fresh coffee, the girls opt for a second plate of "Cracktown Fries" instead. With antique chandeliers, gold glitter paint and deep red and green sofa benches with giant velvet cushions, the place has the feel of a jazz-age opium den, a strangely swanky, though not entirely inappropriate atmosphere for the area. Dealers and prostitutes mingle across the street, like a small satellite of the drugs ghetto on nearby East Hastings. I walked there the following day, past the agitated men clutching crack pipes in full view of the police, the pale, emaciated hookers pounding the pavement barefoot, and a filthy character in devastated leather, crawling into a dumpster all in broad daylight.

But this is the 'hood the Organ calls home, particularly Smyth, a lifer in Vancouver's downtown east side. Stocks, born in Summerland in the Okanagan, talks about the city's struggle to clean up the area, a process the impending Olympics may hasten, but even some locals are reluctant to venture anywhere near Needle Park at night. Honey and Tinseltown, a well-programmed but architecturally grotesque movie multiplex, are two indicators of an attempted gentrification, but Tinseltown's shops have failed and the pub is empty.

Whether or not they're influenced by the squalor in this pocket of the city or the rain that falls for more than half of every year, the Organ have like minds in Vancouver's wealth of the dark and downbeat bands, such as the acts on their old label, Global Symphonic. Links are easily drawn between the Organ and subterranean rockers Radio Berlin, or their Mint label-mates Young and Sexy, though the mere mention of that band's song "The City You Live In Is Ugly" draws protest and statements of civic pride from all sides.

"Vancouver's a beautiful city!" gushes Smyth, and, of course, she's right. The natural sights, smells and sounds of Canada's Western metropolis aren't unique to Vancouver, but they're novel to the majority of Canadians, whose environment consists of flat farmland, grey urbania and extreme weather.

"Vancouver's got character," adds Smyth. "A busy downtown section, mountains, country right nearby, and it's always been a really multicultural city. Also, it's isolated geographically from the U.S. and the rest of Canada, so it has a solid scene because everyone's just hanging around making music. There's a lot of personality in what's going on here."

"It's got all these awesome secrets, too" says bassist Ashley Webber, who grew up in the quiet country burg of Whonnock, BC. "So much of my life is spent walking or riding my bike through Vancouver."

Sketch also stalks the streets on a regular basis, finding lyrical inspiration at every other turn. "That's all I seem to write about I actually feel like I have to tone it down," she says. "My lyrics are always connected to where I am or what I'm looking, and they often come when I'm walking by myself in the city."

In particular, Sketch's everyday pastime is poetically detailed in "Memorize the City," possibly the Organ's greatest achievement to date. Aside from the album's epilogue a brief, morose moan of Smyth's organ the song is Grab That Gun's triumphant finale, an upbeat, infectious double elegy to Sketch's ever-present "you" (whoever you are) and the unique urban landscape of her hometown: "I walk through the streets and memorise the city / I count every light until I reach the shore / Sometimes I close my eyes and you're not very pretty / Sometimes I can't believe I've had those thoughts before."

Inside the Organ

Five folks who inspired and assisted during formative years.

Ron Obvious

This world-renowned engineer was Katie Sketch's mentor at Vancouver's Warehouse studio, where she worked her way up to become his assistant. "Any musician should have a complete understanding of the recording studio process," he says, adding that Sketch (then 18) was enthusiastic and well-liked around the Warehouse so much so that its owner, Bryan Adams, gave her a red telecaster guitar. Obvious also introduced Sketch to what she calls "that '80s sound," compiling tapes of bands he thought she'd appreciate as a violinist (Roxy Music, Ultravox) and a singer with an "amazing natural vocal pitch" (Siouxsie and the Banshees, Nina Hagen, Kate Bush). Now removed from the music biz, Obvious is content to be a fan. "How could I not be completely proud of the Organ? They're great!"

Barb Choit (aka Barb Sketch)

This New York City-based conceptual artist and experimental rocker (with the Mentals) is one of Katie Sketch's childhood friends. "We went to an all-girls high school together," she says. "My first impression of Katie was She must be cool.'" Later, Choit, Sketch and Sarah Efron formed Full Sketch, an instrumental act that was "like the Organ with no words, a little bit of surf guitar and more wrong notes," says Choit, still known as Barb Sketch with her West coast friends. "The idea was Sketch sisters forever'," she explains, "but Sarah quit the band, so we call her Sarah ex-Sketch."

Sarah Efron

"I met Katie Sketch when we worked morning shifts at a wretched cinnamon bun shop," says Efron, "but we really became friends on a road trip where we ended up breaking down in the redneck town of Hermiston, Oregon. On this trip, we decided to form a band and call it Full Sketch." After playing bass with the Organ for a year, in which time they recorded their debut seven-inch, this ex-Sketch became an ex-Organ. "The rock'n'roll lifestyle wasn't for me." Currently a freelance radio and print journalist, Efron was also the news director at UBC's CITR, where she, Sketch and Choit co-hosted a raunchy late-night call-in program called The Dead Air Show.

Sean Keane

Keane and Carlos Williams, who preside over Global Symphonic Records, were immediately wooed by the Organ's seven-inch. At a party thrown by Radio Berlin's Chris Frey, the label and the band approached each other with caution. "They were just as shy as us," recalls Keane. "At that meeting, we decided we'd do the Sinking Hearts EP. We've since got to know the Organ really well. I can honestly say they're most sincere, hard-working people around. We love the music they play and we love them as friends. I'm not kidding they've been that good to us."

Jonathan Simkin

This entertainment lawyer, who co-runs 604 Records with Nickelback's Chad Kroeger, caught a fever at an Organ show and the only cure was signing the band. "It was love at first sight!" says Simkin. "I was hypnotised by Katie's voice, by the haunting, catchy melodies, intelligent lyrics, sparse arrangements. And I couldn't take my eyes off the band. I was absolutely smitten." Simkin pursued the band relentlessly for about ten months, until they succumbed to a hybrid deal, signing with both 604 and Mint Records. "It was like falling in love with a person, which is how it should be when you sign a band. No was not an option."

In 2002, Sinking Hearts introduced a band that evoked the minor chord melancholy of the early '80s, some songs achieving that irresistible fusion of dour poetry and danceable tunes. Whether it was simply nostalgia, the charm of audibly amateurish musicians with such a distinctive vision and style, or the allure of a female band with unisex appeal, these girls swiftly made away with hearts and minds across the continent, and with the recent release of their exceptional LP, Grab That Gun, it appears we've all made a sound investment.

Visiting Vancouver for the first time in a decade, I arranged a rendezvous with the Organ on my second night in city. From a street corner in downtown's east side, we make our way to Honey, an ornate lounge-pub only steps away from the band's rehearsal space. Singer Katie Sketch is instantly talkative, though she rarely makes eye contact and occasionally cradles her face in her hands. The Organ have a rep for lacking confidence, petrified at the sight of the ever-expanding crowds that flock to their shows, and subsequently seeming detached on stage, a trait some mistake for either drop-dead cool or "snobby." They have a tendency to be overly modest, but it's hard to argue with the girls when they say they're hardly virtuoso musicians.

Katie Sketch is the exception. Having studied violin from the age of three, competitive skiing in her pubescent years, studio engineering in her late teens and, currently, psychology at SFU, it's clear that the rich croon and discreet charisma she displays on stage are grounded in discipline.

The classically-trained multi-instrumentalist certainly put her skills to use throughout the three years it took to get the Organ together. Organist Jenny Smyth, the youngest (22) and bubbliest of the bunch, entered the picture when she joined Sketch's instrumental trio, Full Sketch. After that band dissolved, the duo branched off to audition players for their new band, a gruelling process that finally culled self-taught guitarist Debora Cohen. Cohen is conspicuously silent throughout the interview, uttering only five words at the tail end of a crude tour story: "I slept in cat piss."

"Deb, this is getting so boring with you talking so much!" gibes Sketch, who more than makes up for her band-mate's silence. Sitting on either side of Cohen are drummer Shelby Stocks, at 28 the eldest and possibly wisest of the gang, and bassist Ashley Webber, a friendly girl with a funny bleak streak. The rhythm section joined the band late in the game, after Sketch abandoned auditions and decided to simply hire like-minded people and teach them how to play.

"It's not like the five of us got together and spontaneously created this," Sketch explains. "Jenny and I had a direction we wanted to go in and then we slowly recruited people. We could tell if someone didn't get it, which is why we had to get rid of so many players. It's funny sometimes people say the band's moving really quickly, but I feel like I've been doing this forever."

Five years is a long time, long enough for this band to assemble the right crew, develop their craft, tour the continent, record 13 songs and sign to three labels first Global Symphonic, then 604 and Mint. In the public eye, the Organ is a new band, but its members say they've matured significantly since its formation, both as people (Smyth: "I was a child!"; Webber: "I was a goth!"), and as musicians.

"Last year was all about practicing and getting better," says Sketch. "Now I feel like we're actually musicians we're really tight, and proud of what we do."

Heaven Knows I'm Miserable Now

Heaven Knows I'm Miserable NowThroughout the interview, Honey's sound system blares a hot mix of '70s and '80s classics, everything from Frankie Goes to Hollywood to the Ramones to Lene Lovich to the Information Society. Smyth's Hammond 123XL "Romance Series" organ and her '60s rock'n'soul-influenced playing hardly qualify as the stuff of synth-pop (though she jokes that her other band, the Ewoks, "pioneered electroclash"), and they don't bow low enough before the Velvet Underground and Gang of Four to resemble New York's more raucous retro fad. Nevertheless, the Organ are often grouped with a general revivalist trend, sometimes loosely termed "new new wave." (Ten years ago, UK bands like Elastica and Supergrass were allegedly "the new wave of the new wave," but I digress.)

"New wave is a haircut," says Sketch, as confused as anyone about the meaning of the term. "We're too dark and moody for that."

Regardless, new wave's grand dames Debbie Harry, Siouxsie Sioux and Alison Moyet often pop up in reference to Sketch's vocals, while the Smiths, the Cure and Joy Division form the grand triad of elder boy bands that the Organ is always compared to. Along with the similarly downcast and lo-fi aesthetic, it's hard to miss the echo of Robert Smith and Johnny Marr in Cohen's guitar and the assertive Peter Hook-isms in Webber's bass lines.

Eloquently illustrating cold, pain, darkness, despair, loneliness, longing, self-mutilation and suicide, Sketch's lyrics also reflect her musical influences, as well as the band's collective history of clinical depression and severe social alienation.

"I listen to a lot of music with happy lyrics, but when I try writing a lighter song, it always sounds faux," Sketch says. "And if I'm in a good headspace, I'm not sitting at home writing, I'm doing something with friends or drinking at a bar. I've tried writing lyrics at 3 p.m. at the beach, but it always works better late at night, when I'm feeling manic about something."

Not surprisingly, the girls have a wealth of morbid thoughts in mind. They're all anxious about the following day's trip to Toronto, partly due to their press and promo obligations, mostly due to the flight itself. Only the previous day, NORAD fighter jets had been summoned to "escort" an Air Canada plane into Vancouver because of some bogus terrorist threat, so Webber and Smyth sporadically wallow in morbid talk about hijackers, crashes and violent turbulence, turning Cohen's olive complexion pale. In maternal mode, Stocks elbows in with a pointed shush: "No more death talk!"

Along with the depressive nature of their lyrics and their banter, the double entendres of their name and their album title would have made an Organ fan out of Freud. If that weren't enough, Sketch uttered this excellent slip about Grab That Gun: "Whenever I mention the title, I get an ere- a reaction," she says, as her band-mates stifle laughter.

But Sketch has a sense of humour too, notably regarding the full frontal Morrissey thread that runs through her singing. Grab That Gun's main attraction for sway-heads is a song that dates back to Full Sketch: "Steven Smith," a not-so-covert tribute to Steven Patrick Morrissey. Its recently-penned lyrics, Sketch's darkest to date, aren't literally about the ex-Smith, but they are the source of the Organ's LP title.

In an amusing coincidence, the cover of Morrissey's new album, You Are the Quarry (released a week before Grab That Gun) is a gangster-chic photo of the Mozzer clutching a Tommy gun. This little factoid elicits a loud flurry of responses from the band: "Fuck off!" "Oh my God, no!" "That's hilarious!" "That's brutal or is it good? I can't tell."

Jumping Someone Else's Train

Apart from a touch of guitar ring and vocal reverb, the Organ's early songs were bell- and whistle-free, lo-fi recordings lacking that homogenised coating that dulls so much mainstream music. Though their minimal arrangements and unpolished playing leave the band vulnerable to criticism, those qualities are clearly part of what makes the Organ so endearing.

"I like the flaws and the edgy sound that we have," says Stocks, "it's a nice, refreshing, real thing." Unfortunately, the real thing was lost on the original version of Grab That Gun, produced by the band's friend Kurt Dahle of the New Pornographers. It's an uneasy discussion, as the girls don't want to hurt feelings or create friction, but they describe Dahle's record as mechanical, clean and perfect.

"We're so not about perfection," says Stocks. "But Kurt was only trying to do what he thought was best for us. He wanted to take us in a bigger direction than we were willing to put ourselves out for, 'cause we're not those kind of girls."

"No, we're not," Sketch concurs. "It was a different kind of success. It felt like those mixes would suit us if we all decided to wear crop-tops and get total makeovers, and maybe some plastic surgery in this area," she adds, hoisting her mammaries. "It just did not make me feel comfortable."

Making matters more awkward, the New Pornographers and the Organ toured the U.S. together almost immediately after the girls heard what Dahle had to offer.

"It was really hard for us not to bring it up on tour, because it felt like we were whispering behind his back," Stocks explains. "In retrospect, I guess we were, but we just didn't want to get into bad vibes."

"When we got back, the record was literally mixed and going to mastering when we had a fit," says Sketch. "Stop! Wait, wait, wait we're not putting this out.'"

Apart from the effect it might have on their friendship with Dahle, what made this a particularly difficult decision was the mounting pressure the band was facing from everyone who expected the album to drop last fall.

"People I really trust kept telling me, It's taking way too long, you have to put the album out now or everybody's gonna forget about you,'" says Smyth.

"We didn't fucking care," adds Stocks, "we had to put something out that we were all gonna stand by."

Salvaging only a few bass and drum tracks, the band re-recorded the entire album, this time with their own gear. It was engineered by Paul Forgues, mixed by Todd Simko and overseen by Sketch, who eagerly applied her engineering expertise.

"I was very, very, very, very involved," she says. "We couldn't afford, mentally, physically or financially, to have any more mistakes."

"We looked forward to putting out something great with Kurt, and a lot of work went into it, but there's no hate it's just too bad," says Stocks. There's also consensus among the girls that they wouldn't have been ready to release and promote the album as far back as last fall.

"We weren't mature enough then," says Smyth. "Now, we can handle our shit." Addressing her band-mates, she asks "can you imagine if we were putting this record out when I was having that nervous breakdown?!"

After a round of laughter, Stocks pipes in with, "Yeah, that would have been a nightmare. Anyway, the album we've got is something we're really happy with, so it was all worth it."

Memorize the City

Memorize the CityWhen Honey's friendly waiter comes around with fresh coffee, the girls opt for a second plate of "Cracktown Fries" instead. With antique chandeliers, gold glitter paint and deep red and green sofa benches with giant velvet cushions, the place has the feel of a jazz-age opium den, a strangely swanky, though not entirely inappropriate atmosphere for the area. Dealers and prostitutes mingle across the street, like a small satellite of the drugs ghetto on nearby East Hastings. I walked there the following day, past the agitated men clutching crack pipes in full view of the police, the pale, emaciated hookers pounding the pavement barefoot, and a filthy character in devastated leather, crawling into a dumpster all in broad daylight.

But this is the 'hood the Organ calls home, particularly Smyth, a lifer in Vancouver's downtown east side. Stocks, born in Summerland in the Okanagan, talks about the city's struggle to clean up the area, a process the impending Olympics may hasten, but even some locals are reluctant to venture anywhere near Needle Park at night. Honey and Tinseltown, a well-programmed but architecturally grotesque movie multiplex, are two indicators of an attempted gentrification, but Tinseltown's shops have failed and the pub is empty.

Whether or not they're influenced by the squalor in this pocket of the city or the rain that falls for more than half of every year, the Organ have like minds in Vancouver's wealth of the dark and downbeat bands, such as the acts on their old label, Global Symphonic. Links are easily drawn between the Organ and subterranean rockers Radio Berlin, or their Mint label-mates Young and Sexy, though the mere mention of that band's song "The City You Live In Is Ugly" draws protest and statements of civic pride from all sides.

"Vancouver's a beautiful city!" gushes Smyth, and, of course, she's right. The natural sights, smells and sounds of Canada's Western metropolis aren't unique to Vancouver, but they're novel to the majority of Canadians, whose environment consists of flat farmland, grey urbania and extreme weather.

"Vancouver's got character," adds Smyth. "A busy downtown section, mountains, country right nearby, and it's always been a really multicultural city. Also, it's isolated geographically from the U.S. and the rest of Canada, so it has a solid scene because everyone's just hanging around making music. There's a lot of personality in what's going on here."

"It's got all these awesome secrets, too" says bassist Ashley Webber, who grew up in the quiet country burg of Whonnock, BC. "So much of my life is spent walking or riding my bike through Vancouver."

Sketch also stalks the streets on a regular basis, finding lyrical inspiration at every other turn. "That's all I seem to write about I actually feel like I have to tone it down," she says. "My lyrics are always connected to where I am or what I'm looking, and they often come when I'm walking by myself in the city."

In particular, Sketch's everyday pastime is poetically detailed in "Memorize the City," possibly the Organ's greatest achievement to date. Aside from the album's epilogue a brief, morose moan of Smyth's organ the song is Grab That Gun's triumphant finale, an upbeat, infectious double elegy to Sketch's ever-present "you" (whoever you are) and the unique urban landscape of her hometown: "I walk through the streets and memorise the city / I count every light until I reach the shore / Sometimes I close my eyes and you're not very pretty / Sometimes I can't believe I've had those thoughts before."

Inside the Organ

Five folks who inspired and assisted during formative years.

Ron Obvious

This world-renowned engineer was Katie Sketch's mentor at Vancouver's Warehouse studio, where she worked her way up to become his assistant. "Any musician should have a complete understanding of the recording studio process," he says, adding that Sketch (then 18) was enthusiastic and well-liked around the Warehouse so much so that its owner, Bryan Adams, gave her a red telecaster guitar. Obvious also introduced Sketch to what she calls "that '80s sound," compiling tapes of bands he thought she'd appreciate as a violinist (Roxy Music, Ultravox) and a singer with an "amazing natural vocal pitch" (Siouxsie and the Banshees, Nina Hagen, Kate Bush). Now removed from the music biz, Obvious is content to be a fan. "How could I not be completely proud of the Organ? They're great!"

Barb Choit (aka Barb Sketch)

This New York City-based conceptual artist and experimental rocker (with the Mentals) is one of Katie Sketch's childhood friends. "We went to an all-girls high school together," she says. "My first impression of Katie was She must be cool.'" Later, Choit, Sketch and Sarah Efron formed Full Sketch, an instrumental act that was "like the Organ with no words, a little bit of surf guitar and more wrong notes," says Choit, still known as Barb Sketch with her West coast friends. "The idea was Sketch sisters forever'," she explains, "but Sarah quit the band, so we call her Sarah ex-Sketch."

Sarah Efron

"I met Katie Sketch when we worked morning shifts at a wretched cinnamon bun shop," says Efron, "but we really became friends on a road trip where we ended up breaking down in the redneck town of Hermiston, Oregon. On this trip, we decided to form a band and call it Full Sketch." After playing bass with the Organ for a year, in which time they recorded their debut seven-inch, this ex-Sketch became an ex-Organ. "The rock'n'roll lifestyle wasn't for me." Currently a freelance radio and print journalist, Efron was also the news director at UBC's CITR, where she, Sketch and Choit co-hosted a raunchy late-night call-in program called The Dead Air Show.

Sean Keane

Keane and Carlos Williams, who preside over Global Symphonic Records, were immediately wooed by the Organ's seven-inch. At a party thrown by Radio Berlin's Chris Frey, the label and the band approached each other with caution. "They were just as shy as us," recalls Keane. "At that meeting, we decided we'd do the Sinking Hearts EP. We've since got to know the Organ really well. I can honestly say they're most sincere, hard-working people around. We love the music they play and we love them as friends. I'm not kidding they've been that good to us."

Jonathan Simkin

This entertainment lawyer, who co-runs 604 Records with Nickelback's Chad Kroeger, caught a fever at an Organ show and the only cure was signing the band. "It was love at first sight!" says Simkin. "I was hypnotised by Katie's voice, by the haunting, catchy melodies, intelligent lyrics, sparse arrangements. And I couldn't take my eyes off the band. I was absolutely smitten." Simkin pursued the band relentlessly for about ten months, until they succumbed to a hybrid deal, signing with both 604 and Mint Records. "It was like falling in love with a person, which is how it should be when you sign a band. No was not an option."