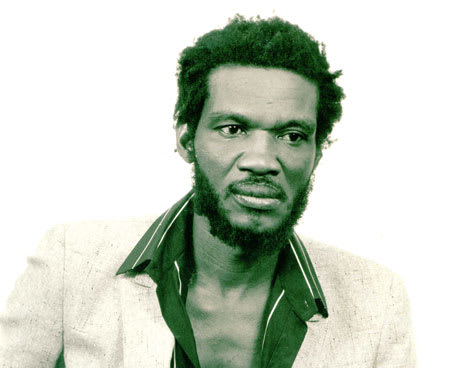

Roots reggae producer Winston Holness' nickname "Niney" stems from an unfortunate accident in a workshop where he lost his thumb. As for the "Observer," well, that part of his nickname is explained a little bit in this interview. Niney was one of the most important producers of the first half of the '70s. Though he rubbed shoulders with many of reggae's all-time greats, he is likely best known for establishing Dennis "The Crown Prince Of Reggae" Brown's superstardom with a series of definitive collaborations. Niney may have become less active since the '70s, but his classic material has generated many reissues. Fittingly, his smash hit "Blood And Fire" became the name of the best-ever reggae reissue label. Since January, reggae uber-label VP has issued a greatest hits collection entitled Roots With Quality on its 17 North Parade subsidiary, and also reissued the Niney-produced Mr. McGregor disc by Freddie McGregor and the Heptones' Meet The Now Generation.

Exclaim! spoke to Niney over the phone from London.

Did you like how the greatest hits collection came out?

Yes! They do good work. I like it, they really put the art into it. I got a fair deal from them.

Let's roll back the clock to the late '60s, what was going on in Jamaica in 1967 to '68 where there was a lot of independent production going on?

Really my work started in 1968, in reggae. Before that was the rock steady. But the excitement started in 1968.

Who did you start working with? Who taught you the tools of production?

Well I started working by myself. I met guys like [ska vocalist] Derrick Morgan and these guys and asked them to sing a record with me.

You were known just as much as a vocalist as a producer in those days.

I never came out as a producer first, I came out as a vocalist first.

Did your vocal experience make you into a better producer later on?

Yes, because if I didn't know anything about vocals then I couldn't get such classic sounds out there. True, I am a vocalist, I know when a singer sounds right, and when he makes a mistake, I can guide him and I can take a note and make him hear. It's like a jockey who becomes a trainer.

Your reputation really begins with "Blood and Fire" in 1971? That was a gigantic hit - do you think that changed Jamaican music?

Yes. A lot of things happened in those times. Even little things in the words start to come into other songs. And the rhythm was revolutionary. In those days there were a lot of smooth things a lot of love things going on. Then the rastamen started to rebel.

Did Bob Marley base "Duppy Conqueror" on your song?

No. [He explains that the chorus to "Blood and Fire" is actually lifted from a Wailers record, not the other way around.] What really happened is they sang a song called "Love Light" and it was a kind of soul song, when I did "Blood and Fire" it wasn't near that, they would get no idea off that song. It was in a different context; the same words but a different preacher. Me and Bob [Marley] never foght over that thing, it was just a misunderstanding. Someone went and told Bob that the song that I sing was supposed to be his song. With that kind of song, [rastas] don't want to see baldhead [Niney didn't have dreadlocks at the time] sing that song.

You were friends with Lee Perry back then too?

Lee ["Scratch"] Perry and Bunny [Striker] Lee. [Striker is] the one who motivated me to reach so far in music. I used to be around Scratch but he never gave me the ball to bowl... Scratch was a man who was completely against me, who would compete - you know "I can do anything better than you." Bunny Lee was never like that. He'd say "Niney, you control the studio, I'm not working today." I make rhythms for Bunny. I made him a rhythm called "Slip Away" but one day Scratch take it, calls it "Prisoner Of Love" and it hit #1 in England. He never put my name or Bunny Lee's name on it. We had a big fight about it.

You always hear about Lee Perry being crazy, you don't hear about his competitive side as much.

I was the one who was behind it. Scratch know that. He never gave me any credit. He was the same way with Bob Marley and Bunny Wailer. He even gave my ideas to them! I was a nobody at that time.

I was always under the impression that the relationship was more friendly than that.

Oh yeah, he's alright, but he's very selfish sometimes. You know he's got his crazy ways [laughs].

Around this time you started working with Dennis Brown. That must have been more fulfilling. What was the first song you worked on?

"Westbound Train," which was his #1 song [in 1972]. The album was going to called "Westbound Train" but then "Money In My Pocket" came out and that's what they called the album. He's one of the best artists I ever worked with. He listened and was ready to learn. I worked with him right up until he passed on.

And the rhythms you laid down with the Soul Syndicate became known as some of the most classic dubs that King Tubby ever put out. Tell me about your relationship with Tubby.

Me and Tubbys have a good relationship. I know Tubbys from years before anyone else. I introduced Lee Perry and Bunny Lee to Tubbys. He had a little room and he decided to make a little studio out of it. Byron Lee [of Dynamic Sound Studios] had a little board, which broke down. Tubbys bought the board and fixed it, and decided to turn his bedroom into a studio and there he started to started to mix songs for his [mobile] sound system. He would cut the dubs, and promote them, so everybody loved that! So now, when people would release a song, they would go by Tubbys. That is how he got so great. He was a great mixer, he knew what he wanted, what was running the streets.

You worked pretty prolifically during the '70s, but by the time the '90s came around your work from this period started getting more attention. What was your reaction when you found out that a reggae reissue label had named itself after your biggest hit?

Well, Steve Barrow [head of Blood and Fire] is a nice guy. Me and him and Bunny Lee had some hard times with Trojan Records, so we sat down and said, let's form a company. Trojan has a vault they're not giving to anybody, we can make a new vault. He said yes, and that was the idea was Blood and Fire, and we thought we were going to work together. But after a while we heard that him and Simply Red [Mick Hucknall was the financial backer of the label] were working together... that's just life.

Are you working much these days?

I'm building a studio these days. I have a full blown Pro Tools system and I'm setting up an analog system with it. I'll start working in it this year. I can't tell you what I'm going to do just yet, but I think the music industry is going to look at what I'm doing and they're going to develop a personal machine to do what I'm doing. This is why I'm not doing anything before I get copyrighted, get my work protected.

Exclaim! spoke to Niney over the phone from London.

Did you like how the greatest hits collection came out?

Yes! They do good work. I like it, they really put the art into it. I got a fair deal from them.

Let's roll back the clock to the late '60s, what was going on in Jamaica in 1967 to '68 where there was a lot of independent production going on?

Really my work started in 1968, in reggae. Before that was the rock steady. But the excitement started in 1968.

Who did you start working with? Who taught you the tools of production?

Well I started working by myself. I met guys like [ska vocalist] Derrick Morgan and these guys and asked them to sing a record with me.

You were known just as much as a vocalist as a producer in those days.

I never came out as a producer first, I came out as a vocalist first.

Did your vocal experience make you into a better producer later on?

Yes, because if I didn't know anything about vocals then I couldn't get such classic sounds out there. True, I am a vocalist, I know when a singer sounds right, and when he makes a mistake, I can guide him and I can take a note and make him hear. It's like a jockey who becomes a trainer.

Your reputation really begins with "Blood and Fire" in 1971? That was a gigantic hit - do you think that changed Jamaican music?

Yes. A lot of things happened in those times. Even little things in the words start to come into other songs. And the rhythm was revolutionary. In those days there were a lot of smooth things a lot of love things going on. Then the rastamen started to rebel.

Did Bob Marley base "Duppy Conqueror" on your song?

No. [He explains that the chorus to "Blood and Fire" is actually lifted from a Wailers record, not the other way around.] What really happened is they sang a song called "Love Light" and it was a kind of soul song, when I did "Blood and Fire" it wasn't near that, they would get no idea off that song. It was in a different context; the same words but a different preacher. Me and Bob [Marley] never foght over that thing, it was just a misunderstanding. Someone went and told Bob that the song that I sing was supposed to be his song. With that kind of song, [rastas] don't want to see baldhead [Niney didn't have dreadlocks at the time] sing that song.

You were friends with Lee Perry back then too?

Lee ["Scratch"] Perry and Bunny [Striker] Lee. [Striker is] the one who motivated me to reach so far in music. I used to be around Scratch but he never gave me the ball to bowl... Scratch was a man who was completely against me, who would compete - you know "I can do anything better than you." Bunny Lee was never like that. He'd say "Niney, you control the studio, I'm not working today." I make rhythms for Bunny. I made him a rhythm called "Slip Away" but one day Scratch take it, calls it "Prisoner Of Love" and it hit #1 in England. He never put my name or Bunny Lee's name on it. We had a big fight about it.

You always hear about Lee Perry being crazy, you don't hear about his competitive side as much.

I was the one who was behind it. Scratch know that. He never gave me any credit. He was the same way with Bob Marley and Bunny Wailer. He even gave my ideas to them! I was a nobody at that time.

I was always under the impression that the relationship was more friendly than that.

Oh yeah, he's alright, but he's very selfish sometimes. You know he's got his crazy ways [laughs].

Around this time you started working with Dennis Brown. That must have been more fulfilling. What was the first song you worked on?

"Westbound Train," which was his #1 song [in 1972]. The album was going to called "Westbound Train" but then "Money In My Pocket" came out and that's what they called the album. He's one of the best artists I ever worked with. He listened and was ready to learn. I worked with him right up until he passed on.

And the rhythms you laid down with the Soul Syndicate became known as some of the most classic dubs that King Tubby ever put out. Tell me about your relationship with Tubby.

Me and Tubbys have a good relationship. I know Tubbys from years before anyone else. I introduced Lee Perry and Bunny Lee to Tubbys. He had a little room and he decided to make a little studio out of it. Byron Lee [of Dynamic Sound Studios] had a little board, which broke down. Tubbys bought the board and fixed it, and decided to turn his bedroom into a studio and there he started to started to mix songs for his [mobile] sound system. He would cut the dubs, and promote them, so everybody loved that! So now, when people would release a song, they would go by Tubbys. That is how he got so great. He was a great mixer, he knew what he wanted, what was running the streets.

You worked pretty prolifically during the '70s, but by the time the '90s came around your work from this period started getting more attention. What was your reaction when you found out that a reggae reissue label had named itself after your biggest hit?

Well, Steve Barrow [head of Blood and Fire] is a nice guy. Me and him and Bunny Lee had some hard times with Trojan Records, so we sat down and said, let's form a company. Trojan has a vault they're not giving to anybody, we can make a new vault. He said yes, and that was the idea was Blood and Fire, and we thought we were going to work together. But after a while we heard that him and Simply Red [Mick Hucknall was the financial backer of the label] were working together... that's just life.

Are you working much these days?

I'm building a studio these days. I have a full blown Pro Tools system and I'm setting up an analog system with it. I'll start working in it this year. I can't tell you what I'm going to do just yet, but I think the music industry is going to look at what I'm doing and they're going to develop a personal machine to do what I'm doing. This is why I'm not doing anything before I get copyrighted, get my work protected.