Its safe to say that being a working musician has always been a tough gig. In the pre-electricity days, virtuoso performers who could draw society crowds earned a suitable stack of shillings, but if you were second fiddle, you barely made enough to keep yourself in rosin and horsehair, let alone home and family.

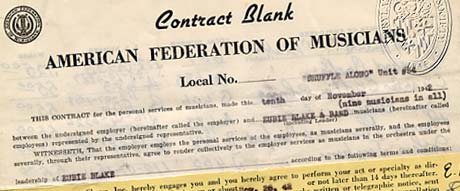

With the rise of the middle class and the advent of technologies that enabled wider performance and distribution of music (Victrolas, radio, moving pictures) and more musicians to play it, the need to standardise wages for working musicians became acute. Across North America in the 1800s, musicians put together their own Mutual Aid Societies ad hoc support groups that provided basic widow-and-orphan protection. In 1896, the American Federation of Labor helped delegates among these societies create a charter for the American Federation of Musicians, the AFM. Canadian musicians had their own chapters of the AFM within ten years.

The AFM is not a collective bargaining agent for musicians everywhere in every circumstance. Rather, it is set up to negotiate scale agreements on behalf of its members. The AFM negotiates with different kinds of employers of musicians: record labels, clubs, symphonies, and broadcasters, for example. If it can persuade those employers that hiring union musicians is in their best interest, the employers then sign up for a scale agreement.

Scale agreements set rates of pay for different kinds of engagements. How much you should be paid depends mainly on a) what role you have in the group; b) where the gig takes place; and c) who the end market is. Leaders get paid more than sidemen; New Years Eve gigs pay better than any given Tuesday. Rates vary from local to local, depending on the success of individual negotiations and what each market will bear.

In exchange for membership in the AFM, members pay union dues in the form of a set percentage of the income they make from union-sanctioned gigs. The collected dues are used to pay the salaries of AFM executives, stewards and staff; to cover AFM operating costs; to invest in pension and other benefit programs, and whatever else the union needs money for. Daily operations of each AFM local are authorised by its constitution and bylaws, which are set out and amended from time to time by the members themselves at regular meetings.

Much has changed over the hundred-odd years of the union, and its relevance is now questioned by musicians and employers alike. Throughout most of the last century, most musicians in Canada worked in radio, symphonies, orchestras and big bands. In the 1950s, going to see a band meant dressing to the nines and hitting the nearest ballroom. Until the punk-propelled DIY explosion of the late 70s, there wasnt much of a bar scene and not that many casual or part-time musicians could expect to launch a living as weekend warriors. The rise of the independent scene changed all that: you could play in a band and keep your day job. Indeed, you had to, given that non-union gigs paid (and still pay) diddly compared to union scales.

This created problems for the union and its members. Never mind that non-AFM members dont contribute union dues: the perception was that non-union bands were taking jobs away from dues-paying members. Across Canada, AFM locals responded differently to the situation; some locals kept blacklists of offending clubs, promoters and bands, making it almost impossible for musicians doing anything outside of the Top 40 cover band genre to get gigs. In other cities (especially Toronto), the union took a more relaxed stance. As it always has, market trends of supply and demand drove competition for gigs and pay scales accordingly.

The blacklist days have generally set sail, but the AFM still approves of its locals leadership keeping a watchful eye on the club scene and disciplining union members and signatories when they break the rules. Says the AFMs International Representative Alan Willaert, "It gives us a certain amount of control over the market. Thats important because unfortunately, young musicians tend to love the race to the bottom. They undercut each other, saying Well do it for $50, Well, well do it for nothing. Eventually the market is an absolute disgrace and club owners get used to not paying anything for live entertainment. Then its like starting over again, like going back to 1986. We do like to have a certain amount of control because it regulates the business and it makes musicians carry on in a business-like manner despite themselves.

Richard Underhill, founding Shuffle Demon and full-time sax man, has been an AFM member for over 20 years, and while hes grateful to the union for sorting out pay-related conflicts in his early career, he wonders about its future in the face of a radically changing industry. "I think the union is trying to be more relevant and valuable. Some people are talking about unionising [popular Toronto venue] Lees Palace, but I think its a bad idea. There should be a place where kids can play and cut their teeth, a training ground where people who are not quite professional musicians can go for it. I guess with the way the industry is going [the union] doesnt feel so relevant.

Union member and singer-songwriter Kevin Fox is also dubious. Discussing the paperwork- and meeting-heavy operations of the AFM, he says, "Today, theres no one out trying to nail you [for mixing union and non-union activities], but the fact is, no one is playing by the rules. The only reason we join the union is to get [American work visas] P-2s and get union rates with the CBC.

Those arent insubstantial reasons to join, but beyond helping secure visas, the union is only as useful and relevant as its membership requires it to be. The AFM was initially founded by musicians who were powerfully motivated to improve their work and pay conditions: they got together and made it happen. Over the years, as those conditions continued to improve, the running of musicians affairs was left more and more to union administrators. Individual musicians lost their sense of militancy and began to view the union as a sort of annoying functionary rather than a tool for improved negotiating status. Today, as with many labour organisations, attendance at regular AFM meetings tends to be weak, meaning that the few zealous meeting-goers end up driving the agenda, leaving the slack-offs to grouse, rather illegitimately, about the lack of democracy in union leadership.

Many union musicians have only the sketchiest idea of what responsibilities and benefits come with their membership, and Willaert doesnt have a lot of patience for members who are clued out. "Thats their fault, he says. "Its not hard to pick up the local bylaws or tariff of fees those are available at any meeting or at the office or online. Or a phone call. Its not a big reach.

What it all tallies up to is this: Do your research before you join the union. If you are currently a member and youre not getting what you need from it, your choices are to quit or get off the bandstand. Heaven knows working musicians need all the help they can get, especially from each other.

With the rise of the middle class and the advent of technologies that enabled wider performance and distribution of music (Victrolas, radio, moving pictures) and more musicians to play it, the need to standardise wages for working musicians became acute. Across North America in the 1800s, musicians put together their own Mutual Aid Societies ad hoc support groups that provided basic widow-and-orphan protection. In 1896, the American Federation of Labor helped delegates among these societies create a charter for the American Federation of Musicians, the AFM. Canadian musicians had their own chapters of the AFM within ten years.

The AFM is not a collective bargaining agent for musicians everywhere in every circumstance. Rather, it is set up to negotiate scale agreements on behalf of its members. The AFM negotiates with different kinds of employers of musicians: record labels, clubs, symphonies, and broadcasters, for example. If it can persuade those employers that hiring union musicians is in their best interest, the employers then sign up for a scale agreement.

Scale agreements set rates of pay for different kinds of engagements. How much you should be paid depends mainly on a) what role you have in the group; b) where the gig takes place; and c) who the end market is. Leaders get paid more than sidemen; New Years Eve gigs pay better than any given Tuesday. Rates vary from local to local, depending on the success of individual negotiations and what each market will bear.

In exchange for membership in the AFM, members pay union dues in the form of a set percentage of the income they make from union-sanctioned gigs. The collected dues are used to pay the salaries of AFM executives, stewards and staff; to cover AFM operating costs; to invest in pension and other benefit programs, and whatever else the union needs money for. Daily operations of each AFM local are authorised by its constitution and bylaws, which are set out and amended from time to time by the members themselves at regular meetings.

Much has changed over the hundred-odd years of the union, and its relevance is now questioned by musicians and employers alike. Throughout most of the last century, most musicians in Canada worked in radio, symphonies, orchestras and big bands. In the 1950s, going to see a band meant dressing to the nines and hitting the nearest ballroom. Until the punk-propelled DIY explosion of the late 70s, there wasnt much of a bar scene and not that many casual or part-time musicians could expect to launch a living as weekend warriors. The rise of the independent scene changed all that: you could play in a band and keep your day job. Indeed, you had to, given that non-union gigs paid (and still pay) diddly compared to union scales.

This created problems for the union and its members. Never mind that non-AFM members dont contribute union dues: the perception was that non-union bands were taking jobs away from dues-paying members. Across Canada, AFM locals responded differently to the situation; some locals kept blacklists of offending clubs, promoters and bands, making it almost impossible for musicians doing anything outside of the Top 40 cover band genre to get gigs. In other cities (especially Toronto), the union took a more relaxed stance. As it always has, market trends of supply and demand drove competition for gigs and pay scales accordingly.

The blacklist days have generally set sail, but the AFM still approves of its locals leadership keeping a watchful eye on the club scene and disciplining union members and signatories when they break the rules. Says the AFMs International Representative Alan Willaert, "It gives us a certain amount of control over the market. Thats important because unfortunately, young musicians tend to love the race to the bottom. They undercut each other, saying Well do it for $50, Well, well do it for nothing. Eventually the market is an absolute disgrace and club owners get used to not paying anything for live entertainment. Then its like starting over again, like going back to 1986. We do like to have a certain amount of control because it regulates the business and it makes musicians carry on in a business-like manner despite themselves.

Richard Underhill, founding Shuffle Demon and full-time sax man, has been an AFM member for over 20 years, and while hes grateful to the union for sorting out pay-related conflicts in his early career, he wonders about its future in the face of a radically changing industry. "I think the union is trying to be more relevant and valuable. Some people are talking about unionising [popular Toronto venue] Lees Palace, but I think its a bad idea. There should be a place where kids can play and cut their teeth, a training ground where people who are not quite professional musicians can go for it. I guess with the way the industry is going [the union] doesnt feel so relevant.

Union member and singer-songwriter Kevin Fox is also dubious. Discussing the paperwork- and meeting-heavy operations of the AFM, he says, "Today, theres no one out trying to nail you [for mixing union and non-union activities], but the fact is, no one is playing by the rules. The only reason we join the union is to get [American work visas] P-2s and get union rates with the CBC.

Those arent insubstantial reasons to join, but beyond helping secure visas, the union is only as useful and relevant as its membership requires it to be. The AFM was initially founded by musicians who were powerfully motivated to improve their work and pay conditions: they got together and made it happen. Over the years, as those conditions continued to improve, the running of musicians affairs was left more and more to union administrators. Individual musicians lost their sense of militancy and began to view the union as a sort of annoying functionary rather than a tool for improved negotiating status. Today, as with many labour organisations, attendance at regular AFM meetings tends to be weak, meaning that the few zealous meeting-goers end up driving the agenda, leaving the slack-offs to grouse, rather illegitimately, about the lack of democracy in union leadership.

Many union musicians have only the sketchiest idea of what responsibilities and benefits come with their membership, and Willaert doesnt have a lot of patience for members who are clued out. "Thats their fault, he says. "Its not hard to pick up the local bylaws or tariff of fees those are available at any meeting or at the office or online. Or a phone call. Its not a big reach.

What it all tallies up to is this: Do your research before you join the union. If you are currently a member and youre not getting what you need from it, your choices are to quit or get off the bandstand. Heaven knows working musicians need all the help they can get, especially from each other.