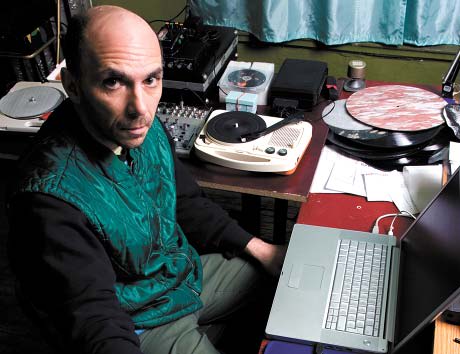

Martin Tétreaults studio in Montréals East End looks like the back room of your local electrical repair shop tables are covered in turntables, wires, tone arms, electric motors, mixers, and, incongruously, a recently acquired laptop. This friendly jumble of gear speaks to his unique approach to sound as musician, artist and mechanic.

In the world of the DMC scratch throw-downs, Tétreault may seem like an oddity, but hes combined finely honed improvisational skills with a love and dedication to the sound of motors, needles and playing surfaces that have brought him international acclaim.

He has appeared on 22 recordings with other artists and 39 under his own name (many available at www.ambiancesmagnetiques.com) and has played and recorded with some of the leading innovators on the noise/experimental scene including Otomo Yoshihide, Ikue Mori, Christian Marclay and Rene Lussier. Hes also collaborated with Kid Koala and Japans off kilter punk pop goddess-turned-experimentalist Haco and is considered one of the foremost noise artists in the world today. As a result he tours constantly and is also in great demand in the world of modern dance and performance art. His way of making sound has less to do with the digital manipulation of signal than the mechanical and electrical sounds made by each turntable and turntable artefact. Right now he owns more than 25 decks with not one single Technics 1200 in sight, including one player gifted to him by Kid Koala. "He said it wasnt spinning properly so itd be good for me, Tétreault laughs.

"Each one has their own unique sound, Tétreault explains, "whether its caused by a problem with the motor, static in the signal, or maybe the spin is not so regular. While this may seem like working with a highly unstable source, he maintains a "trust in the physique of sound, literally observing and manipulating the voice of each deck. Tétreault also prepares his cartridges by replacing needles with other materials and creates "free tonearms by using just the cartridges. He is a big fan, as well, of the 50 to 60 hertz hum that lurks in every sound device, bringing it to life in various ways from the sound of the tonearm with the motor running at different speeds to using a mic on the deck itself. All these create loops that can be altered by the other audio effects links in the chain.

There are essentially three elements involved in the process: the turntable, a mixer and other small electronics (mostly a nanoverb and a distortion pedal) and prepared surfaces. The mixer serves as the EQ patch and pan control, and the small electronics add their own features of harmonic distortion and manipulation.

Some of the most interesting facets of this kind of music making involve playing surfaces themselves everything from MACtac glued onto vinyl, LPs cut from other materials or rubbing metal or sandpaper on arms or needles, to slashing vinyl blanks live to get the staggered clicking rhythms that drive some of his pieces.

Tétreault "likes the risk of live performance where the process of making a work is "action and reaction setting up a sequence and letting it run, then creating an "audio accident by maybe dropping a record onto the deck or in the case of the last gig he did on a tour with Otomo Yoshihide picking up a partially destroyed turntable with loose objects inside and shaking it. He would start with the sound of this accident and continue with another section, "like a staircase where each stair is a different accident. He has a palette of colours (types of turntables, surfaces and effects) but what finally comes out as the composition is unknown. He runs the turntables into his own mixer with the house mixer slaved from that; sometimes he uses four decks as mono signals to create a kind of surreal quadraphonic stereo sound. All combine live or in studio in, what Tétreault calls "constructions. This is no abstract frame of reference, as he attributes the love of the tactile nature of his work to his education and work in fine art (which also continues). Even in making music, physicality is key; he "needs to touch, build things, make surfaces and likes to see and touch the sound generators part of the process of creation.

"One day, I said, instead of working on paper or making drawings, lets do it on something else like a record, he says. "For me it was not a record but a black circle so I cut it and glued it back together with other records and played it. It was like live sampling.

Tétreault is always interested in possibilities and this has kept him creating on a very high level. He is constantly travelling the border between a sophisticated and highly defined art aesthetic and the gritty reality of his materials. Combined with a strong and focused work ethic, it keeps him and us in the forefront of creative music.

In the world of the DMC scratch throw-downs, Tétreault may seem like an oddity, but hes combined finely honed improvisational skills with a love and dedication to the sound of motors, needles and playing surfaces that have brought him international acclaim.

He has appeared on 22 recordings with other artists and 39 under his own name (many available at www.ambiancesmagnetiques.com) and has played and recorded with some of the leading innovators on the noise/experimental scene including Otomo Yoshihide, Ikue Mori, Christian Marclay and Rene Lussier. Hes also collaborated with Kid Koala and Japans off kilter punk pop goddess-turned-experimentalist Haco and is considered one of the foremost noise artists in the world today. As a result he tours constantly and is also in great demand in the world of modern dance and performance art. His way of making sound has less to do with the digital manipulation of signal than the mechanical and electrical sounds made by each turntable and turntable artefact. Right now he owns more than 25 decks with not one single Technics 1200 in sight, including one player gifted to him by Kid Koala. "He said it wasnt spinning properly so itd be good for me, Tétreault laughs.

"Each one has their own unique sound, Tétreault explains, "whether its caused by a problem with the motor, static in the signal, or maybe the spin is not so regular. While this may seem like working with a highly unstable source, he maintains a "trust in the physique of sound, literally observing and manipulating the voice of each deck. Tétreault also prepares his cartridges by replacing needles with other materials and creates "free tonearms by using just the cartridges. He is a big fan, as well, of the 50 to 60 hertz hum that lurks in every sound device, bringing it to life in various ways from the sound of the tonearm with the motor running at different speeds to using a mic on the deck itself. All these create loops that can be altered by the other audio effects links in the chain.

There are essentially three elements involved in the process: the turntable, a mixer and other small electronics (mostly a nanoverb and a distortion pedal) and prepared surfaces. The mixer serves as the EQ patch and pan control, and the small electronics add their own features of harmonic distortion and manipulation.

Some of the most interesting facets of this kind of music making involve playing surfaces themselves everything from MACtac glued onto vinyl, LPs cut from other materials or rubbing metal or sandpaper on arms or needles, to slashing vinyl blanks live to get the staggered clicking rhythms that drive some of his pieces.

Tétreault "likes the risk of live performance where the process of making a work is "action and reaction setting up a sequence and letting it run, then creating an "audio accident by maybe dropping a record onto the deck or in the case of the last gig he did on a tour with Otomo Yoshihide picking up a partially destroyed turntable with loose objects inside and shaking it. He would start with the sound of this accident and continue with another section, "like a staircase where each stair is a different accident. He has a palette of colours (types of turntables, surfaces and effects) but what finally comes out as the composition is unknown. He runs the turntables into his own mixer with the house mixer slaved from that; sometimes he uses four decks as mono signals to create a kind of surreal quadraphonic stereo sound. All combine live or in studio in, what Tétreault calls "constructions. This is no abstract frame of reference, as he attributes the love of the tactile nature of his work to his education and work in fine art (which also continues). Even in making music, physicality is key; he "needs to touch, build things, make surfaces and likes to see and touch the sound generators part of the process of creation.

"One day, I said, instead of working on paper or making drawings, lets do it on something else like a record, he says. "For me it was not a record but a black circle so I cut it and glued it back together with other records and played it. It was like live sampling.

Tétreault is always interested in possibilities and this has kept him creating on a very high level. He is constantly travelling the border between a sophisticated and highly defined art aesthetic and the gritty reality of his materials. Combined with a strong and focused work ethic, it keeps him and us in the forefront of creative music.