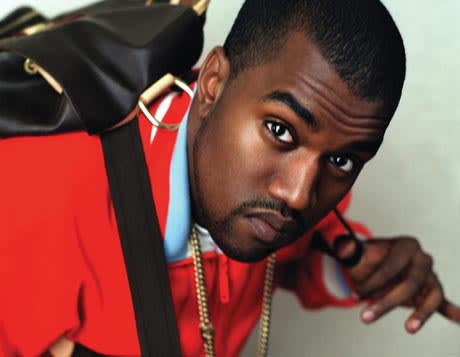

Kanye West is a study in contrasts. He is a producer of household names like Alicia Keys and Jay-Z, yet he's worked the boards for comparatively subterranean hip-hop stalwarts Dilated Peoples and Slum Village. As an MC, he's comfortable sharing the mic with the incongruous MC pairing of Mos Def and Freeway, and with the celestial tones of the Harlem Boys Choir all on the same song. His rhymes decry a slavish devotion to wanton materialism one moment; he admits his own complicity the next.

In truth, West knows exactly what he's doing and on his debut The College Dropout, he pointedly thrives on emphasising his contradictions. "I'm bridging the gaps," he says matter-of-factly. It may seem utterly natural for an artist to explore his inner yin-yang, but in a mainstream hip-hop field intent on selling one-dimensional caricatures of pimp and thug imagery, West's regular guy approach makes him a refreshing character.

While he is rapidly gaining the ubiquitous notoriety producers like the Neptunes and Timbaland garnered when they first came up, West started out in Chicago, a city that's not known for its extensive hip-hop clout. West learned the trade by hanging around record stores and spots that he knew producer No I.D. the chief sonic architect of Windy City rhymer Common's bona fide 1994 classic Resurrection would frequent.

"No I.D. is my mentor," says West. "I always give him props, the person I looked up to. Sometimes we may not talk for a year at a time, but I always gave him respect for being a person that I could look to and say Damn, I know somebody who's actually making money so this shit is possible.'"

West cultivated his own soulful sound and toiled through numerous ghost production gigs before getting his producing break on Jay-Z's 2001 album The Blueprint. His own distinctive take on using sped-up soul vocal samples on his tracks, a technique notably used by Wu-Tang Clan's the RZA, proved influential, spawning a host of imitators. In the process, the reign of the digitally cold keyboard-driven production style was dislodged as the predominant sound emanating from hip-hop's birthplace.

While West has moved on from relying on the chipmunk soul' aesthetic, he's still eager to build on the days when he rhymed and battled in Common's basement and to disprove the prevalent theory that hip-hop producers can't really rock the mic. While he's hardly the second coming of Rakim, what West lacks in complex lyrical patterns he makes up for with digestible yet unflinching social commentaries on spirituality and racism, charismatic wit and a willingness to explore his foibles and vulnerabilities.

"I just wear my heart on my sleeve," he says. "That's kind of my niche. It's kinda like what [Wu-Tang Clan's] Ghostface does, and Eminem. Just really being honest about what's going on." One example is "Through The Wire," a song West recorded with his jaw wired shut after a near-fatal car accident. It recounts the experience and immediate aftermath; it's emblematic of the prevailing underdog theme on The College Dropout. "I feel like that was God saying I can hand you the world or at any given time I can take it away from you.' I think Through the Wire' was also a song that actually made people care about me and it kinda set me apart. That I went through something they could relate to."

With a captive audience, Kanye West's deceptively simple musical and lyrical style creates space for contradiction: where the innocent singing of kids can represent a defiant middle finger to the establishment and humorous party joints can reference African diamond-trading controversies. "I never want to copy anything," he says. "I make my music straight from the heart and try to keep it creative and I want it to stand out as much as possible."

In truth, West knows exactly what he's doing and on his debut The College Dropout, he pointedly thrives on emphasising his contradictions. "I'm bridging the gaps," he says matter-of-factly. It may seem utterly natural for an artist to explore his inner yin-yang, but in a mainstream hip-hop field intent on selling one-dimensional caricatures of pimp and thug imagery, West's regular guy approach makes him a refreshing character.

While he is rapidly gaining the ubiquitous notoriety producers like the Neptunes and Timbaland garnered when they first came up, West started out in Chicago, a city that's not known for its extensive hip-hop clout. West learned the trade by hanging around record stores and spots that he knew producer No I.D. the chief sonic architect of Windy City rhymer Common's bona fide 1994 classic Resurrection would frequent.

"No I.D. is my mentor," says West. "I always give him props, the person I looked up to. Sometimes we may not talk for a year at a time, but I always gave him respect for being a person that I could look to and say Damn, I know somebody who's actually making money so this shit is possible.'"

West cultivated his own soulful sound and toiled through numerous ghost production gigs before getting his producing break on Jay-Z's 2001 album The Blueprint. His own distinctive take on using sped-up soul vocal samples on his tracks, a technique notably used by Wu-Tang Clan's the RZA, proved influential, spawning a host of imitators. In the process, the reign of the digitally cold keyboard-driven production style was dislodged as the predominant sound emanating from hip-hop's birthplace.

While West has moved on from relying on the chipmunk soul' aesthetic, he's still eager to build on the days when he rhymed and battled in Common's basement and to disprove the prevalent theory that hip-hop producers can't really rock the mic. While he's hardly the second coming of Rakim, what West lacks in complex lyrical patterns he makes up for with digestible yet unflinching social commentaries on spirituality and racism, charismatic wit and a willingness to explore his foibles and vulnerabilities.

"I just wear my heart on my sleeve," he says. "That's kind of my niche. It's kinda like what [Wu-Tang Clan's] Ghostface does, and Eminem. Just really being honest about what's going on." One example is "Through The Wire," a song West recorded with his jaw wired shut after a near-fatal car accident. It recounts the experience and immediate aftermath; it's emblematic of the prevailing underdog theme on The College Dropout. "I feel like that was God saying I can hand you the world or at any given time I can take it away from you.' I think Through the Wire' was also a song that actually made people care about me and it kinda set me apart. That I went through something they could relate to."

With a captive audience, Kanye West's deceptively simple musical and lyrical style creates space for contradiction: where the innocent singing of kids can represent a defiant middle finger to the establishment and humorous party joints can reference African diamond-trading controversies. "I never want to copy anything," he says. "I make my music straight from the heart and try to keep it creative and I want it to stand out as much as possible."