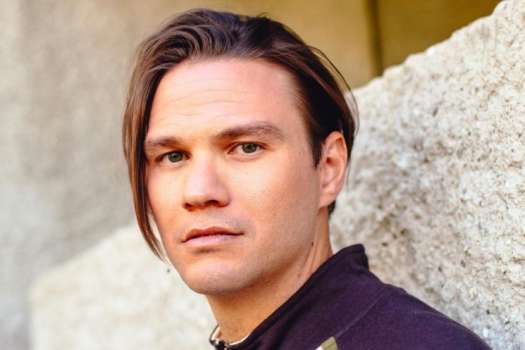

Theres no doubt Tim Kinsella is one of rocks most polarising figures. In his 12 years as Joan of Arcs restless and ever-prolific front-man, hes amassed an impressive body of work, both with his main project and its myriad of offshoots. In the process, the 33-year-old Chicago native has earned nearly as much praise as he has criticism, attracting labels such as ambitious, innovative and genius right alongside purposely difficult and pretentious. Yet such sharp division lines have done little to deter Kinsellas output, whether it was with his highly influential and now-defunct emo act Cap'n Jazz or now with Joan of Arc, his solo work or one of his many other bands, such as Owls, Make Believe and Friend/Enemy. As Kinsella prepares to take to the road in support of one of Joan of Arcs most welcoming pieces of off-kilter rock, Boo Human, the soon to be masters of writing student let us in on his new album, film work, family and his aversion to the rocknroll lifestyle.

How did you set about to write the new album, Boo Human?

The writing process is pretty easily integrated into my lifestyle. I truly have the luckiest, most privileged, easiest life, so I have a lot of time to play music. I mean, Im a bartender and Ive been doing that for about eight or nine years, just so I would have the time to focus on music. But I am always very aware on whether or not I am not concentrating on creative output. There is definitely an urgency to be active creatively so I justify my privileged lifestyle. With making records, the songs just kind of pile up and this energy reserve builds up and then some alarm clock goes off saying, "Okay, make the record now. And so with the new one, I just picked through all these demos and home recordings, threw two-thirds away on the first listen, and then booked the studio time and came up with some ideas of what the band would be.

The last Joan of Arc record,Eventually, All at Once, almost played like a solo record, with you taking on most things yourself. With the new one, however, you have enlisted 14 different musicians. How did you decide which players were going to be on the record and how did you organise everyone?

It was hard to nail anyone down specifically, so we just said, "Okay everyone, just come by when you can. We had a sign-up sheet, people would show up at noon and I would go, "Okay, this is todays group. But really, it was kind of based on a practical audit of who was available. Joan of Arc sort of operate now where there are maybe 18 people who are in the band, and we set something up and see whoever is available. Its the same with touring. We just figure out who is available, get together and sort out who is going to do what later.

Did you set out to do anything really different from previous albums with this record?

The lyrics are definitely a very different approach. Its always meant a lot to me to have very shaded and open meanings to the songs, so people could attach their own meanings. I mean, Ive always been a big fan of lyrics in songs that youve heard a million times but then suddenly its like, "Hey that lyric in the second verse doesnt really make any sense. Ive always been really drawn to that. Ive always been more interested in creating a playing field for people to impose their own meanings on. But the lyrics on this record are much more straightforward and there is just this, "This is how I feel. This is what Im going through. Here it is. Theres definitely an aspect of vulnerability in the words that isnt in the usual Joan of Arc operating procedure.

There is a line in the Boo Human song "Shown and Told where you mention a hermaphrodite stepfather. How does that fit into this new lyrical approach?

Well, that one is an exception and there are a few of those on this record. There are a few mysterious moments like that one that I would prefer to leave mysterious. Actually, when we were playing the other week I was, "Now, what is a hermaphrodite stepfather? And I got hung up on that line for a minute. And I think thats why Ive always enjoyed leaving my lyrics more abstract because when we are on tour playing all these songs live, a different line will hit me each night, and I can see something new it the songs myself.

On the press release for Boo Human put out by your label, Polyvinyl, they call the album one of your most accessible records. Do you agree with that?

Selling something on the adjective of accessibility seems like the most meaningless sales point to me. Ive been part of enough records now that when people are approaching it there is a bit of a stigma, being, "Well, is this going to be a listenable one or some indulgent one, so I know thats what the label is referring to. But what kind of standard is accessibility? I mean, who is ever like, "Man, thats awesome. Totally accessible!

Do you ever feel you are being overly difficult on your records?

Well, its not something I ever really think about. But I never want to turn an audience off or something. Im not being willfully obtuse for any reason. I think what sometimes comes out as us being difficult is really just us being playful. And I think often people dont recognise the degree of playfulness in what we do.

Do you think getting married a few years ago has impacted the approach you take to the band and taken away some of the tension that so often was found in the early Joan of Arc records?

Oh, definitely. Its given me a much greater sense of feeling settled and feeling at home than I ever had before. Obviously being married has affected every aspect of my life its the central commitment and priority of my life. But I would say Make Believe probably has had a greater impact on Joan of Arc sounding more relaxed than my marriage has. There was once a vast, wide-open parameter of what Joan of Arc could sound like in our minds, but Make Believe specialised a distinct quadrant of that, which removed Joan of Arc from ever having to cover that territory.

And which territory is that?

Aggressiveness. In Make Believe weve always been really aware of the waveform nature of reality, where the physics and the mystics overlap just the resonance of this table versus sound versus smell, and how light and sound are the same waves but just at different frequencies. So in Make Believe we were always really aware of which pitch we wanted to operate at one where there would be an ecstatic aspect to it but also a discomforting one.

You left Make Believe last year, crediting the departure to feeling a disconnection to the "rock band lifestyle.

Yeah, I still dont feel connect to that. I mean, Im more looking forward to this upcoming Joan of Arc tour more than any in years because I havent been on tour in over a year now, so its not like my day job is living in a van anymore. And when I get home, I know Im going to be starting school so I wont be going on tour again for a couple of years again. I mean, the five of us who are going on tour all have different things happening in our lives in the next couple months, so this might be our last chance.

But was this the only reason why you quit Make Believe?

It was taking so much of my time and there was really no sonic space to be anything but the front-man in that band. And Im definitely aware of a persona. I mean, in Joan of Arc I feel totally free to speak my mind and speak for myself. In Make Believe, I was always the spokesmen for we four. There was a responsibility to that and there was no other aspect for me to contribute than as a front-man. There is something satisfying about being a front-man, but I dont know what it is, and if I did, it might sicken me. And there is something rewarding about it, but not in the lethal dose I was having to do it at.

Why did you rejoin and start the band up again?

After I quit, we re-established how I could possibly keep doing the band. And we realised the only way we could do it was by each of us having our own sane, happy lives that would overlap whenever they could without all the stress that was there before.

So will there be more Make Believe records?

Yeah, if and when time permits. But we arent going to kill ourselves to do it anymore.

Your brother Mike recently did an interview with us. In it, he talked about how for him being in Joan of Arc was such a relaxing, non-stressful situation. Maybe not in Make Believe, but do you feel the same way when you participate in other side-projects feeling really relaxed and free of stress?

You know, I would say I feel that way even in Joan of Arc and Make Believe because I never feel that there is a stress in either band where I feel like, "Oh man, I really have to provide tonight. I really have to do it. I feel like I have such trust in Make Believe. I know those three are going to nail things. And my contribution is really sort of in the background for a front-man, and in Joan of Arc too. I have a trust that the psychic energy between us is going to come together, and if anyone is feeling sluggish between us, they will be raised the level of the rest of us instead of bringing anyone down. I feel relaxed about both.

What kind of role do you think family plays in Joan of Arc?

I dont know. It was never an issue or anything, or something I thought about. Not to diminish my connection with Mike or my cousin Nate who plays in the band, but the familiarity amongst everyone in Joan of Arc is very familial. These would be people I would be getting dinner with or going to get a drink with or walking to get a coffee with anyway. No one has ever been in or out of Joan of Arc because of their technical aspects as a musician. The central aspect is our relationship with each other; the music is just a byproduct.

You recently directed and wrote your own film,Orchard Vale. How did that experience compare with making music?

Well, it was definitely the hardest thing Ive been apart of and wiped me out emotionally, physically, financially and psychically for a year. Basically it destroyed the lives of everyone who was part of it, but it exists.

Could you give a brief rundown of the storyline?

Its basically about people being together, being trapped and dealing with being trapped without ever having an explanation of whats trapping them or why they are being trapped or whats beyond their little world. So it can metaphorically be read for any sort of prisoner situation, whether that be the nations trapped on Earth having to figure out how to distribute resources or trapped in a painful relationship somehow, or even trapped in being human. Its all about this tension of transcending something and trying to see beyond it and how you co-operate to do that. Which, of course, sounds much more complex than it really is, and its all sort of simple. And the movie is actually kind of a comedy.

So would you want to do another film?

We all came out of it running, and Ive written two screenplays since, but making another movie isnt something I am immediately pushing for now. Orchard Vale got rejected from 35 out of the 36 festivals we submitted it to, so that was certainly a bummer, to put so much energy and all our money into something and have it be something that people are not able to see.

So what are you going to do with the film now?

Well, the DVD came out in Japan, but only there. I should have spent the last couple of months securing some kind of distribution here, but the stress of getting it done and the devastating effect it had on the lives on everyone involved left a bad taste in everyones mouth in even touching it now. But it was definitely an intense learning experience.

This is a bit ancient history, but why did the band break up after you released The Gap in 2000, only to reform a few years later?

I think it was just the stress of where can we can from here and largely due to our views on how to be a band and how we could continue together. You know, I did Owls right after that, which, in my mind, the only way I could return to music after The Gap was to return to the people I was in my first band with, return to like, "Lets get inside the practice space, record these songs, and do it exactly like they sound in the space. It was very much a return to garage basics, for me. And it was only really when Owls proved unsustainable that Joan of Arc reemerged because I was still working on things and I didnt know why I should call it anything else if it was still me, Sam [Zurick] and Mike.

How do you feel about The Gap now?

I may have a softer spot for it than a lot of the records just because I know the anguish of rearing it. I wish the best of all of our records, but we were going through so much getting The Gap made. I have very sort of warm and cuddly feelings for it, and dont think that is the reaction most people have towards it. Its a pretty cold record. But maybe thats why I feel I have to be warm towards it, to sort of balance it out.

With Joan of Arc, you guys have gone from being these scrappy, young art punks to elder statesmen in the experimental indie world. How do you feel about your current situation as a band?

Its strange. There arent a lot of bands that exist for 12 or 13 years. Now its definitely more the e.e. cummings idea of process over progress that maintains us. Its part of that whole rock music existing as the commercial jingles for consumer capitalism of always wanting a new thing. And all Joan of Arc can offer is a new Joan of Arc, but you basically know what you are getting into. So obviously its harder to sell a bands tenth record than its first because its not a new thing. But I feel very comfortable with our situation. I dont have any tension with it.

To go back to Boo Human, what do you hope listeners take away from this record that they havent from your older stuff?

There are these certain records in your life that mean a lot to you, whether they are by Gordon Lightfoot, or Phil Collins or John Cale. There are these songs that are there for you when you need them but maybe dont even register to you that they are there for you. I just wanted to make that kind of record because I feel Ive never made one of those before. I wanted to make a record that could exist for people when they needed it.

How did you set about to write the new album, Boo Human?

The writing process is pretty easily integrated into my lifestyle. I truly have the luckiest, most privileged, easiest life, so I have a lot of time to play music. I mean, Im a bartender and Ive been doing that for about eight or nine years, just so I would have the time to focus on music. But I am always very aware on whether or not I am not concentrating on creative output. There is definitely an urgency to be active creatively so I justify my privileged lifestyle. With making records, the songs just kind of pile up and this energy reserve builds up and then some alarm clock goes off saying, "Okay, make the record now. And so with the new one, I just picked through all these demos and home recordings, threw two-thirds away on the first listen, and then booked the studio time and came up with some ideas of what the band would be.

The last Joan of Arc record,Eventually, All at Once, almost played like a solo record, with you taking on most things yourself. With the new one, however, you have enlisted 14 different musicians. How did you decide which players were going to be on the record and how did you organise everyone?

It was hard to nail anyone down specifically, so we just said, "Okay everyone, just come by when you can. We had a sign-up sheet, people would show up at noon and I would go, "Okay, this is todays group. But really, it was kind of based on a practical audit of who was available. Joan of Arc sort of operate now where there are maybe 18 people who are in the band, and we set something up and see whoever is available. Its the same with touring. We just figure out who is available, get together and sort out who is going to do what later.

Did you set out to do anything really different from previous albums with this record?

The lyrics are definitely a very different approach. Its always meant a lot to me to have very shaded and open meanings to the songs, so people could attach their own meanings. I mean, Ive always been a big fan of lyrics in songs that youve heard a million times but then suddenly its like, "Hey that lyric in the second verse doesnt really make any sense. Ive always been really drawn to that. Ive always been more interested in creating a playing field for people to impose their own meanings on. But the lyrics on this record are much more straightforward and there is just this, "This is how I feel. This is what Im going through. Here it is. Theres definitely an aspect of vulnerability in the words that isnt in the usual Joan of Arc operating procedure.

There is a line in the Boo Human song "Shown and Told where you mention a hermaphrodite stepfather. How does that fit into this new lyrical approach?

Well, that one is an exception and there are a few of those on this record. There are a few mysterious moments like that one that I would prefer to leave mysterious. Actually, when we were playing the other week I was, "Now, what is a hermaphrodite stepfather? And I got hung up on that line for a minute. And I think thats why Ive always enjoyed leaving my lyrics more abstract because when we are on tour playing all these songs live, a different line will hit me each night, and I can see something new it the songs myself.

On the press release for Boo Human put out by your label, Polyvinyl, they call the album one of your most accessible records. Do you agree with that?

Selling something on the adjective of accessibility seems like the most meaningless sales point to me. Ive been part of enough records now that when people are approaching it there is a bit of a stigma, being, "Well, is this going to be a listenable one or some indulgent one, so I know thats what the label is referring to. But what kind of standard is accessibility? I mean, who is ever like, "Man, thats awesome. Totally accessible!

Do you ever feel you are being overly difficult on your records?

Well, its not something I ever really think about. But I never want to turn an audience off or something. Im not being willfully obtuse for any reason. I think what sometimes comes out as us being difficult is really just us being playful. And I think often people dont recognise the degree of playfulness in what we do.

Do you think getting married a few years ago has impacted the approach you take to the band and taken away some of the tension that so often was found in the early Joan of Arc records?

Oh, definitely. Its given me a much greater sense of feeling settled and feeling at home than I ever had before. Obviously being married has affected every aspect of my life its the central commitment and priority of my life. But I would say Make Believe probably has had a greater impact on Joan of Arc sounding more relaxed than my marriage has. There was once a vast, wide-open parameter of what Joan of Arc could sound like in our minds, but Make Believe specialised a distinct quadrant of that, which removed Joan of Arc from ever having to cover that territory.

And which territory is that?

Aggressiveness. In Make Believe weve always been really aware of the waveform nature of reality, where the physics and the mystics overlap just the resonance of this table versus sound versus smell, and how light and sound are the same waves but just at different frequencies. So in Make Believe we were always really aware of which pitch we wanted to operate at one where there would be an ecstatic aspect to it but also a discomforting one.

You left Make Believe last year, crediting the departure to feeling a disconnection to the "rock band lifestyle.

Yeah, I still dont feel connect to that. I mean, Im more looking forward to this upcoming Joan of Arc tour more than any in years because I havent been on tour in over a year now, so its not like my day job is living in a van anymore. And when I get home, I know Im going to be starting school so I wont be going on tour again for a couple of years again. I mean, the five of us who are going on tour all have different things happening in our lives in the next couple months, so this might be our last chance.

But was this the only reason why you quit Make Believe?

It was taking so much of my time and there was really no sonic space to be anything but the front-man in that band. And Im definitely aware of a persona. I mean, in Joan of Arc I feel totally free to speak my mind and speak for myself. In Make Believe, I was always the spokesmen for we four. There was a responsibility to that and there was no other aspect for me to contribute than as a front-man. There is something satisfying about being a front-man, but I dont know what it is, and if I did, it might sicken me. And there is something rewarding about it, but not in the lethal dose I was having to do it at.

Why did you rejoin and start the band up again?

After I quit, we re-established how I could possibly keep doing the band. And we realised the only way we could do it was by each of us having our own sane, happy lives that would overlap whenever they could without all the stress that was there before.

So will there be more Make Believe records?

Yeah, if and when time permits. But we arent going to kill ourselves to do it anymore.

Your brother Mike recently did an interview with us. In it, he talked about how for him being in Joan of Arc was such a relaxing, non-stressful situation. Maybe not in Make Believe, but do you feel the same way when you participate in other side-projects feeling really relaxed and free of stress?

You know, I would say I feel that way even in Joan of Arc and Make Believe because I never feel that there is a stress in either band where I feel like, "Oh man, I really have to provide tonight. I really have to do it. I feel like I have such trust in Make Believe. I know those three are going to nail things. And my contribution is really sort of in the background for a front-man, and in Joan of Arc too. I have a trust that the psychic energy between us is going to come together, and if anyone is feeling sluggish between us, they will be raised the level of the rest of us instead of bringing anyone down. I feel relaxed about both.

What kind of role do you think family plays in Joan of Arc?

I dont know. It was never an issue or anything, or something I thought about. Not to diminish my connection with Mike or my cousin Nate who plays in the band, but the familiarity amongst everyone in Joan of Arc is very familial. These would be people I would be getting dinner with or going to get a drink with or walking to get a coffee with anyway. No one has ever been in or out of Joan of Arc because of their technical aspects as a musician. The central aspect is our relationship with each other; the music is just a byproduct.

You recently directed and wrote your own film,Orchard Vale. How did that experience compare with making music?

Well, it was definitely the hardest thing Ive been apart of and wiped me out emotionally, physically, financially and psychically for a year. Basically it destroyed the lives of everyone who was part of it, but it exists.

Could you give a brief rundown of the storyline?

Its basically about people being together, being trapped and dealing with being trapped without ever having an explanation of whats trapping them or why they are being trapped or whats beyond their little world. So it can metaphorically be read for any sort of prisoner situation, whether that be the nations trapped on Earth having to figure out how to distribute resources or trapped in a painful relationship somehow, or even trapped in being human. Its all about this tension of transcending something and trying to see beyond it and how you co-operate to do that. Which, of course, sounds much more complex than it really is, and its all sort of simple. And the movie is actually kind of a comedy.

So would you want to do another film?

We all came out of it running, and Ive written two screenplays since, but making another movie isnt something I am immediately pushing for now. Orchard Vale got rejected from 35 out of the 36 festivals we submitted it to, so that was certainly a bummer, to put so much energy and all our money into something and have it be something that people are not able to see.

So what are you going to do with the film now?

Well, the DVD came out in Japan, but only there. I should have spent the last couple of months securing some kind of distribution here, but the stress of getting it done and the devastating effect it had on the lives on everyone involved left a bad taste in everyones mouth in even touching it now. But it was definitely an intense learning experience.

This is a bit ancient history, but why did the band break up after you released The Gap in 2000, only to reform a few years later?

I think it was just the stress of where can we can from here and largely due to our views on how to be a band and how we could continue together. You know, I did Owls right after that, which, in my mind, the only way I could return to music after The Gap was to return to the people I was in my first band with, return to like, "Lets get inside the practice space, record these songs, and do it exactly like they sound in the space. It was very much a return to garage basics, for me. And it was only really when Owls proved unsustainable that Joan of Arc reemerged because I was still working on things and I didnt know why I should call it anything else if it was still me, Sam [Zurick] and Mike.

How do you feel about The Gap now?

I may have a softer spot for it than a lot of the records just because I know the anguish of rearing it. I wish the best of all of our records, but we were going through so much getting The Gap made. I have very sort of warm and cuddly feelings for it, and dont think that is the reaction most people have towards it. Its a pretty cold record. But maybe thats why I feel I have to be warm towards it, to sort of balance it out.

With Joan of Arc, you guys have gone from being these scrappy, young art punks to elder statesmen in the experimental indie world. How do you feel about your current situation as a band?

Its strange. There arent a lot of bands that exist for 12 or 13 years. Now its definitely more the e.e. cummings idea of process over progress that maintains us. Its part of that whole rock music existing as the commercial jingles for consumer capitalism of always wanting a new thing. And all Joan of Arc can offer is a new Joan of Arc, but you basically know what you are getting into. So obviously its harder to sell a bands tenth record than its first because its not a new thing. But I feel very comfortable with our situation. I dont have any tension with it.

To go back to Boo Human, what do you hope listeners take away from this record that they havent from your older stuff?

There are these certain records in your life that mean a lot to you, whether they are by Gordon Lightfoot, or Phil Collins or John Cale. There are these songs that are there for you when you need them but maybe dont even register to you that they are there for you. I just wanted to make that kind of record because I feel Ive never made one of those before. I wanted to make a record that could exist for people when they needed it.