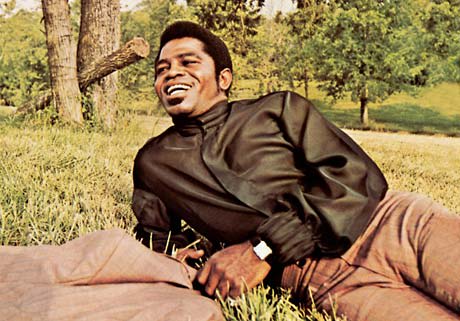

James Brown succeeded from nothing to become a magnetic musician and entertainer. He was responsible for changing the course of black American music several times during the 60s and 70s, and the reverberations from this period in which he garnered 17 number one R&B hits continues to influence music to the present day. Moreover, in his prime he was an inspirational and influential figure who is likely responsible for popularising the word "black to describe those of African descent. Though always known as a difficult person, and with personal troubles affecting his legacy in his latter years, he left behind an incredible body of work that is still widely available.

1933 to 1956

James Brown is born May 3 1933 in a one room shack in the woods near Barnwell, South Carolina. He is presumed stillborn, but his aunt revives him. He lives in extreme rural poverty, supported by his father who works for days at a time in turpentine camps. His parents split up when he is four years old, and he doesnt see his mother again for more than 20 years. At age six, Brown is sent to Augusta, Georgia to live with his aunt who runs a house of prostitution, illegal liquor and gambling. During his school years, Brown is often sent home because of "insufficient clothes. As he grows up, he shines shoes, dances on street corners and hustles any way he can to make ends meet. In the Jim Crow-era South, he is a frequent, random target of horrible acts of racism, including an electrocution incident that almost kills him. He drifts into a life of petty crime, and is arrested on four counts of breaking and entering in 1948. At age 15, he is sentenced to eight to 16 years, initially in prison. He sings gospel while incarcerated, earning the name "Music Box. Transferred to a juvenile facility in Toccoa, Georgia he meets Bobby Byrd while conversing with townies through the prison fence. Brown is paroled in 1952, and joins Byrds gospel group, which soon become known as the Flames. They change their name to the Famous Flames, begin singing secular music and start to fill gigs vacated by ascendant local hero Little Richard. Richards pianist, Fats Gonder, hooks the group up with Richards manager Clint Brantley. In late 1955 the group record a demo of "Please Please Please in a Macon, Georgia radio station, which Brantley circulates to radio and various labels. Both Chicagos Chess Records and Cincinnatis King Records are interested, but a winter storm grounds Leonard Chesss flight in Chicago. Driving through the same storm, Kings talent scout, Ralph Bass, makes it to Georgia to sign the Flames. Although label owner Syd Nathan is sceptical of Basss judgment, the song is re-recorded at Kings Cincinnati studio in February 1956. Credited to James Brown and the Famous Flames, the song eventually makes it to number six on the R&B charts, but has a year-long run, peaking in different cities at different times.

1957 to 1960

The next several releases flop, and Kings support wavers, causing the dissolution of the original Famous Flames, though Byrd stays with Brown off and on until 1972. Scuffling to play gigs in the southeast, his fortunes change in late 1957 when Little Richard quits rocknroll and leaves 40 gigs to be filled. Brown recruits members of Richards band, and Gonder directs the ensemble. Brown and Brantley put up the money to record a demo of one last-ditch effort for King: "Try Me. Released in October 1958, the song hits number one and sells a million copies. This leads to a contract with the well-established Universal Attractions booking agency, headed by Ben Bart. Bart is impressed with Browns talent and determination and encourages his ideas. Although Bart is portly, old, and white the archetype of those whod harassed him during his formative years Brown respects his dedication and support, and eventually refers to him as "Pop. Brown starts playing more extensively in locales beyond the southeast, including the Apollo Theatre in New York, where he flops in 1959. With more gigs, a permanent road band becomes a necessity, and Brown recruits a band from North Carolina fulfil this role. Although there is another commercial dry spell following "Try Me, Browns records become more unusual and assertive, polished to perfection by many nights on the road. Brown begins to use the band in the studio rather than session musicians. He also wants to record instrumental music to showcase the distinctive, syncopated sound of his band, which Nathan refuses. Undaunted, Brown releases "Do The Mashed Potatoes on the Dade label, run by the Godfather of Florida Soul, Henry Stone. It is credited to drummer Nat Kendrick and becomes a national hit. In 1960, Brown breaks through with "Think, a cover of fellow King artists the Five Royales hit from two years previous. "Think earns him his first headlining spot at the Apollo and crosses over to the pop charts.

1960 to 1965

Brown begins to hit the R&B charts with regularity. He is known as the King of the One-Nighters, playing more than 300 dates a year. He begins to schedule recording sessions as needed, wherever the band may be on tour. Although his up-tempo recordings become more and more frequent, his way with a ballad is unmatched, and he has huge hits with "Bewildered, and "Lost Someone. By 1962, his show is breaking box office records, he is hitting the lower reaches of the pop charts, and performs on TV for the first time. Booked for a week long run at the Apollo in October 1962, Brown wants to record his inimitable show. Nathan flatly refuses why would anyone want to buy already-released songs with intrusive crowd noise? Brown invests his own money to record the shows. The recording is a milestone in the history of R&B, as the interplay between Browns frenzied vocals, the stop-on-a-dime precision of the band and the adoring crowd is electric. The LP sells over a million copies, second only the Beach Boys Surfin U.S.A. in 1963. Future Brown tour manager Alan Leeds, then a teenager in Richmond, Virginia, remembers radio station WANT setting aside half an hour every evening at 5 p.m. to play the entire album for weeks on end. The only artist who is bigger than Brown in a "soul vein is Ray Charles; Brown will frequently measure his own career achievements against Charles. In mid 1963, the string drenched "Prisoner Of Love is released, reconfiguring an old pop tune from the 60s into a haunting gospelized ballad, much in the way Charles had done. Also like Charles, Brown wants to expand into jazzier sounds and increase his audience size. Battles continue with Nathan over creative control over his music. In a flagrant breach of contract, Brown records for Smash, a division of Mercury Records. Although he records mostly instrumentals for Smash, he releases a pivotal song, "Out of Sight. This song hits number one and changes the beat of R&B completely: the focus is now on the one, not on beats two and four. In 1964, he performs on the televised TAMI show along with the Beach Boys and the Rolling Stones. As he mashes up the place with a feverish rendition of his 1962 hit "Night Train, Mick Jagger waits nervously in the wings, scared to death to follow Brown. As a new era in Browns career is about to take off, another comes to a close as the Famous Flames vocal group appear for the last time on record with "Maybe The Last Time. In 1965, Brown returns to King for good. Despite the conflicts between Nathan and Brown, there is deep respect between the two men. Brown now has full artistic control of his output and is the promotional focus of the company. His next single is "Papas Got a Brand New Bag (featuring new recruit Maceo Parker on tenor sax), followed by "I Got You (I Feel Good), both million sellers that thoroughly cross over, becoming top ten pop hits.

1966 to 1969

Another major hit is the string-drenched "Its a Mans World. The band gets larger, with Nat Jones replacing Lewis Hamlin as musical director. Browns success is such that he leases a Lear Jet to travel around the country a symbol of success that no other black entertainer has achieved, but also practical in that it frees Brown up to meet his punishing travel demands. He starts to realise he is in a greater position to make social commentary. He demands that his now arena-sized shows are integrated. Redneck Southern venue owners, who have always appreciated the business Brown was able to provide them, comply. He is due to perform his "stay in school anthem "Dont Be A Drop Out on The Ed Sullivan Show, but Sullivan refuses, claiming the song is "too political. Important changes to the band occur in 1967, as polyrhythmic drummer Clyde Stubblefield joins and Alfred "Pee Wee Ellis becomes the arranger. Elliss jazz chops hone Browns rhythmic sensibility even further. Stubblefield, Ellis and Parker are all brilliant contributors to another game-changing single, "Cold Sweat, which again rewrites the beat for R&B and soul jazz, as musicians like Miles Davis begin to take note. Live at the Apollo Volume II is recorded a month after "Cold Sweat drops and finds the band at the crossroads of gospel, old time R&B and newly minted funk. His band remain in a non-stop cycle of touring and recording, with arrangements changing every few weeks to keep the show fresh: there are a half dozen live recordings from this period that feature startlingly diverse renditions of his repertoire. Trombonist Fred Wesley, who joins in 1968, would describe the music in his 2002 autobiography Hit Me, Fred: "At times, the band was totally musical, with beautiful chords and melodies mixing with the constant funky grooves. But, at other times, things happened that totally defied musical explanation. There were chords that were just sounds for effect and rhythms that started and ended wherever they started or ended, not in accord with any time signature or form.

Brown branches out his recording activities to include members of the James Brown revue: Bobby Byrd, Marva Whitney and others. He also incorporates more jazz into his act, and pursues bookings at casinos, where the money is even better. His business enterprises flourish; he purchases radio stations noting, "I used to shine shoes in front of radio stations, now I own radio stations. His influence is such that when he plays the Boston Garden the day after the assassination of Martin Luther King, he persuades a local TV station to film and re-run the concert throughout the night to keep people from rioting. Boston is the only major city in America that stays calm. The apex of such social consciousness is his 1968 single "Say It Loud (Im Black and Im Proud), which reverberates around North America and the world. He is elevated to hero status in Brazil and throughout Africa. Brown is at the crossroads of Vegas aspirations and influence from black militants like H. Rap Brown. With fans rushing the stage everywhere he goes, Brown himself is unsure of the message, as witnessed in a live recording in Dallas from the summer of 1968. Leeds recalls that, "It was a time when he was under pressure from his black audience to retain that presence because he had been anointed as the spokesperson for a certain class of black youth in America. It was the axis of his fan base, and at the same time he coveted crossover acceptance and his ultimate goal was to become an entertainer for all people which he eventually became, of course. He was walking a very thin line to appease both. I dont know if anyone else could have pulled it off. He travels to Vietnam to entertain the troops in 1968 with a white bassist, Tim Drummond though back home, certain factions are not pleased that Drummond is "taking a black mans job. Upon his return, he fills Yankee Stadium, although he is distraught that the show is broken up by overzealous fans; Leeds notes "the old Southern patriarch in James Brown saw it much like the police did: you stupid kids are trashing the show; I came to entertain you! His activities this year garner him dinner at the White House. Upon receiving an invitation to Vice President Hubert Humphreys table, he refuses, stating "Im not the VPs boy. If he wants to meet me halfway, thats fine. Hits in this period become ever funkier: "I Got The Feeling, "Mother Popcorn and "Give It Up Or Turnit-a Loose are all number one hits, test marketed on his radio stations, and broken nationally by his never-ending tours. More changes in the band bring bassist Sweet Charles and the departure of Ellis in early 1969.

1970 to 1971

Brown is a tyrant with his band, fining them for missed notes and unkempt uniforms, withholding their pay to keep them in line, and calling marathon rehearsals just to tire them out and take the fight out of them. His band has stayed with him for years out of fear that they were at the peak of their careers and Brown would interfere with subsequent employment opportunities. The band is also mesmerised by easy sex and drug access on the road. But money is the number one gripe. In his autobiography, Wesley notes, "I figured out that James could make anywhere from $350,000 to $500,000 a week but his payroll remained at about a paltry $6,000 a week. And he acted like he didnt want to give you that. Finally, the band gives Brown an ultimatum before a gig in Columbus, Georgia in March 1970, which Brown rejects. Right hand man Byrd is given the task of shuttling one of Kings session bands to the gig via the Lear jet. The group, named the Pacesetters, features a 19-year-old Bootsy Collins and his brother Phelps. They walk into the venue just as the Orchestra is walking out. They unit gels on stage immediately; two months later they cut "Sex Machine, which trades the polyrhythms of the late 60s Orchestra into the hard funk that would define the newly christened JBs. An African influence creeps in with hand drummer Johnny Griggs joining the band, and becomes more prominent when Brown tours Nigeria in 1970, spending an eye-opening evening at Fela Kutis Afrospot. Bootsy and Catfish inject a youthful abandon to Browns music, which becomes more elastic on the bottom with Bootsys virtuosity, and acid-tinged throughout with Catfishs wailing Hendrix-meets-John Lee Hooker solos. While cutting the classics "Super Bad and "Soul Power, acid literally becomes more than a tinge in the music the Collins brothers become full-on freaks, though Brown is unaware. They leave the band after a gig in spring 1971 during which Collins, tripped out on stage, imagines his bass has turned into a snake. Undaunted, Brown recruits a new set of JBs under the direction of Fred Wesley. This coincides almost exactly with his departure from King Records for Dutch record label Polydor, who are seeking to crack the American market. In a prescient move, Browns catalogue goes with him only Ray Charles had ever undertaken a similar move. The first release of the new JBs and on Polydor is the million selling "Hot Pants.

1971 to 1976

Despite Browns protestations that Polydor doesnt have a clue about what to do with his records, Leeds states "nobody influenced what he was recording in the early days of the Polydor deal, he was still randomly booking studios whenever and wherever he wanted to, and doling out to them the records he wanted released. I dont think they had any influence until the sales started to slow down. Due to the changing marketplace, Brown recording sessions focus more on albums. He also starts up People Records, not his first label, but by far his most successful, with substantial hits by the JBs and backup vocalist Lyn Collins. His band is anchored by the rock solid blues shuffle of drummer John "Jabo Starks. Leeds opines that technically, the 70s band was inferior: "With that band in the 70s he just dummied down the parts. With James Brown you can write rhythmic horn charts that dont require chops but still sound effective. Thats what Fred [Wesley] was doing. He was brilliant at doing that and obscuring thats what it was. Still racking up the hits and expanding his business ventures through 1972, Brown controversially endorses Richard Nixons bid for a second term, which results in his shows at the Apollo being picketed. In 1973, after having finished work on his first soundtrack, Black Caesar, his eldest son Teddy is killed in a car accident. Devastated, he slowly begins to ease up on his workload. Nevertheless, the show goes on, and he continues to produce quality singles including the JBs smash "Doing It To Death which sees Maceo Parker rejoin the band, and "The Payback. He also continues to play important shows, such as the Ali-Foreman Rumble in the Jungle in Zaire documented in When We Were Kings. Around this time, Browns longevity starts to become part of his image when New York DJ Rocky G dubs him "The Godfather of Soul. By 1975, his records are declining in originality and the IRS comes down on him for back taxes and a payola investigation involving his personal manager Charles Bobbit. He sinks a considerable amount of money into a Soul Train-like show called Future Shock, which never makes it out of Georgia. As Brown becomes more and more embroiled in his legal and financial troubles, his band mutinies once again. Leeds notes: "There was a lot of loyalty to Fred Wesley that overcame a lot of things that could have been problems with the band. He was the perfect MD for that band. He had the personality to earn the respect of all the musicians, because the band was in a couple of cliques you had the younger guys who werent really of the same calibre as the established guys, but Fred was equally respected by everyone in the group and became sort of an umbrella figure who didnt allow the cliques to become too separate. It really didnt fall apart until after he left, around 75, and it very quickly fell apart after that. In addition, says Leeds: "Business had slowed down on the road, his overexposure on the arena circuit had caught up with him. After playing these cities twice a year for more than a decade it had finally gotten to the point where it was like Oh, him again? Parker, Wesley and 60s JB survivor Kush Griffith join Bootsy in Parliament-Funkadelic, where they become known as the Horny Horns.

1976 to 1980

Brown continues to release album after album for Polydor but cannot score beyond the lower reaches of the R&B charts now dominated by disco and funk of a much slicker variety than JB can muster. One bright spot artistically is "The Original Disco Man from 1979, featuring Muscle Shoals musicians under the direction of Brad Shapiro (Millie Jackson, Wilson Pickett). He finally leaves Polydor in 1980 and cuts a quick LP in Florida to be released on old friend Henry Stones TK label. "Rapp Payback is a middling hit on the R&B chart. At the same time, he joins other soul legends in the hit movie The Blues Brothers, which ensures that his tours, now scaled back to discos and nightclubs from the arenas he used to do, still pull in decent cash.

1981 to 1991

He appears in another Dan Aykroyd movie, Doctor Detroit, in 1983. He is without a label for several years, with a potential deal with Island Records scuttled by a disastrous session with reggae riddim kings Sly and Robbie. The self-released "Bring it On the same year is followed by a one-off project with hip-hop pioneer Afrika Bambataa entitled "Unity. This is the last truly satisfying record Brown would ever make, but points to his enduring influence on hip-hop. The solo drum sections of his late 60s to early 70s output have become the underpinnings of this new music, and breakdancing is reputed to have started with 1972s "Get On the Good Foot. In 1985 his first CD collection, The CD of JB, introduces him to a new generation of fans. Even more importantly, his appearance in Rocky IV leads to his biggest pop hit in 20 years, the much-maligned "Living in America. In 1986, he is inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. His autobiography is released the following year. Around this time, with all his original material out of print, Polydor begins assembling tracks into well-annotated, historically themed compilations. Seven-inch singles are expanded into their full studio takes to display the full majesty of his band. Some ten comps, including vital collections of the People years, become a library for the new art of sampling, and the James Brown snare sounds of the 60s and 70s become synonymous with old school hip-hop. Unfortunately, around this time, his personal life becomes a shambles. His wife Adrienne introduces him to PCP, and leads to a series of increasingly odd public appearances. In September 1988, doped up and carrying a shotgun, he enters an insurance seminar next to his Augusta office. He is said to have asked seminar participants if they were using his private restroom. Police chased Brown for half an hour before shooting out the tires of his truck. He spends 25 months in jail and is paroled in February1991.

1991 to 2006

Upon his release from prison, a revitalized JB, sounding better than in years, takes the stage at the Wiltern Theatre in Los Angeles for a pay per view concert featuring MC Hammer, Bell Biv Devoe, C + C Music Factory, Kool Moe Dee and En Vogue. Financially depleted from years of litigation and continued IRS garnishment, he hits the road yet again playing more than 200 nights a year to ever bigger ticket prices. The band consists of some old faces like Sweet Charles on keys, and Fred Thomas, bassist for the JBs Mark 2. Far removed from their trendsetting funk days, a JB show continues to be great value for the money. Still in full command of his phrasing, even as his vocal range shrinks, he can still drive the band with precision. Albums are basically a thing of the past. His contract with Scotti Brothers, his label since the "Living in America days, ends in 1993. Despite off and on recording, very little finished product surfaces: his final album is 2002s Next Step. While he is basically sober after his prison stint, he relapses in 1998 and spends a 90-day stint in rehab. In 1999 he finally becomes financially solvent when he converts his future royalties into $30 million in bonds, through the same firm David Bowie had worked with. Finally collecting the accolades of a long and hard-fought career, JB embarks on his Seven Decades of Funk tour in 2004, only to be laid up by prostate cancer. Surgery is successful, and he resumes his activities, publishing a second autobiography in 2005, entitled I Feel Good: A Memoir of a Life of Soul. Although increasingly plagued with arthritis, JB seems in reasonable health in late 2006 when he enters hospital for pneumonia. Suddenly in the early hours of Christmas morning, he passes away, as long-time confidant Rev. Al Sharpton noted, "He was dramatic to the end dying on Christmas Day.

James Brown is born May 3 1933 in a one room shack in the woods near Barnwell, South Carolina. He is presumed stillborn, but his aunt revives him. He lives in extreme rural poverty, supported by his father who works for days at a time in turpentine camps. His parents split up when he is four years old, and he doesnt see his mother again for more than 20 years. At age six, Brown is sent to Augusta, Georgia to live with his aunt who runs a house of prostitution, illegal liquor and gambling. During his school years, Brown is often sent home because of "insufficient clothes. As he grows up, he shines shoes, dances on street corners and hustles any way he can to make ends meet. In the Jim Crow-era South, he is a frequent, random target of horrible acts of racism, including an electrocution incident that almost kills him. He drifts into a life of petty crime, and is arrested on four counts of breaking and entering in 1948. At age 15, he is sentenced to eight to 16 years, initially in prison. He sings gospel while incarcerated, earning the name "Music Box. Transferred to a juvenile facility in Toccoa, Georgia he meets Bobby Byrd while conversing with townies through the prison fence. Brown is paroled in 1952, and joins Byrds gospel group, which soon become known as the Flames. They change their name to the Famous Flames, begin singing secular music and start to fill gigs vacated by ascendant local hero Little Richard. Richards pianist, Fats Gonder, hooks the group up with Richards manager Clint Brantley. In late 1955 the group record a demo of "Please Please Please in a Macon, Georgia radio station, which Brantley circulates to radio and various labels. Both Chicagos Chess Records and Cincinnatis King Records are interested, but a winter storm grounds Leonard Chesss flight in Chicago. Driving through the same storm, Kings talent scout, Ralph Bass, makes it to Georgia to sign the Flames. Although label owner Syd Nathan is sceptical of Basss judgment, the song is re-recorded at Kings Cincinnati studio in February 1956. Credited to James Brown and the Famous Flames, the song eventually makes it to number six on the R&B charts, but has a year-long run, peaking in different cities at different times.

1957 to 1960

The next several releases flop, and Kings support wavers, causing the dissolution of the original Famous Flames, though Byrd stays with Brown off and on until 1972. Scuffling to play gigs in the southeast, his fortunes change in late 1957 when Little Richard quits rocknroll and leaves 40 gigs to be filled. Brown recruits members of Richards band, and Gonder directs the ensemble. Brown and Brantley put up the money to record a demo of one last-ditch effort for King: "Try Me. Released in October 1958, the song hits number one and sells a million copies. This leads to a contract with the well-established Universal Attractions booking agency, headed by Ben Bart. Bart is impressed with Browns talent and determination and encourages his ideas. Although Bart is portly, old, and white the archetype of those whod harassed him during his formative years Brown respects his dedication and support, and eventually refers to him as "Pop. Brown starts playing more extensively in locales beyond the southeast, including the Apollo Theatre in New York, where he flops in 1959. With more gigs, a permanent road band becomes a necessity, and Brown recruits a band from North Carolina fulfil this role. Although there is another commercial dry spell following "Try Me, Browns records become more unusual and assertive, polished to perfection by many nights on the road. Brown begins to use the band in the studio rather than session musicians. He also wants to record instrumental music to showcase the distinctive, syncopated sound of his band, which Nathan refuses. Undaunted, Brown releases "Do The Mashed Potatoes on the Dade label, run by the Godfather of Florida Soul, Henry Stone. It is credited to drummer Nat Kendrick and becomes a national hit. In 1960, Brown breaks through with "Think, a cover of fellow King artists the Five Royales hit from two years previous. "Think earns him his first headlining spot at the Apollo and crosses over to the pop charts.

1960 to 1965

Brown begins to hit the R&B charts with regularity. He is known as the King of the One-Nighters, playing more than 300 dates a year. He begins to schedule recording sessions as needed, wherever the band may be on tour. Although his up-tempo recordings become more and more frequent, his way with a ballad is unmatched, and he has huge hits with "Bewildered, and "Lost Someone. By 1962, his show is breaking box office records, he is hitting the lower reaches of the pop charts, and performs on TV for the first time. Booked for a week long run at the Apollo in October 1962, Brown wants to record his inimitable show. Nathan flatly refuses why would anyone want to buy already-released songs with intrusive crowd noise? Brown invests his own money to record the shows. The recording is a milestone in the history of R&B, as the interplay between Browns frenzied vocals, the stop-on-a-dime precision of the band and the adoring crowd is electric. The LP sells over a million copies, second only the Beach Boys Surfin U.S.A. in 1963. Future Brown tour manager Alan Leeds, then a teenager in Richmond, Virginia, remembers radio station WANT setting aside half an hour every evening at 5 p.m. to play the entire album for weeks on end. The only artist who is bigger than Brown in a "soul vein is Ray Charles; Brown will frequently measure his own career achievements against Charles. In mid 1963, the string drenched "Prisoner Of Love is released, reconfiguring an old pop tune from the 60s into a haunting gospelized ballad, much in the way Charles had done. Also like Charles, Brown wants to expand into jazzier sounds and increase his audience size. Battles continue with Nathan over creative control over his music. In a flagrant breach of contract, Brown records for Smash, a division of Mercury Records. Although he records mostly instrumentals for Smash, he releases a pivotal song, "Out of Sight. This song hits number one and changes the beat of R&B completely: the focus is now on the one, not on beats two and four. In 1964, he performs on the televised TAMI show along with the Beach Boys and the Rolling Stones. As he mashes up the place with a feverish rendition of his 1962 hit "Night Train, Mick Jagger waits nervously in the wings, scared to death to follow Brown. As a new era in Browns career is about to take off, another comes to a close as the Famous Flames vocal group appear for the last time on record with "Maybe The Last Time. In 1965, Brown returns to King for good. Despite the conflicts between Nathan and Brown, there is deep respect between the two men. Brown now has full artistic control of his output and is the promotional focus of the company. His next single is "Papas Got a Brand New Bag (featuring new recruit Maceo Parker on tenor sax), followed by "I Got You (I Feel Good), both million sellers that thoroughly cross over, becoming top ten pop hits.

1966 to 1969

Another major hit is the string-drenched "Its a Mans World. The band gets larger, with Nat Jones replacing Lewis Hamlin as musical director. Browns success is such that he leases a Lear Jet to travel around the country a symbol of success that no other black entertainer has achieved, but also practical in that it frees Brown up to meet his punishing travel demands. He starts to realise he is in a greater position to make social commentary. He demands that his now arena-sized shows are integrated. Redneck Southern venue owners, who have always appreciated the business Brown was able to provide them, comply. He is due to perform his "stay in school anthem "Dont Be A Drop Out on The Ed Sullivan Show, but Sullivan refuses, claiming the song is "too political. Important changes to the band occur in 1967, as polyrhythmic drummer Clyde Stubblefield joins and Alfred "Pee Wee Ellis becomes the arranger. Elliss jazz chops hone Browns rhythmic sensibility even further. Stubblefield, Ellis and Parker are all brilliant contributors to another game-changing single, "Cold Sweat, which again rewrites the beat for R&B and soul jazz, as musicians like Miles Davis begin to take note. Live at the Apollo Volume II is recorded a month after "Cold Sweat drops and finds the band at the crossroads of gospel, old time R&B and newly minted funk. His band remain in a non-stop cycle of touring and recording, with arrangements changing every few weeks to keep the show fresh: there are a half dozen live recordings from this period that feature startlingly diverse renditions of his repertoire. Trombonist Fred Wesley, who joins in 1968, would describe the music in his 2002 autobiography Hit Me, Fred: "At times, the band was totally musical, with beautiful chords and melodies mixing with the constant funky grooves. But, at other times, things happened that totally defied musical explanation. There were chords that were just sounds for effect and rhythms that started and ended wherever they started or ended, not in accord with any time signature or form.

Brown branches out his recording activities to include members of the James Brown revue: Bobby Byrd, Marva Whitney and others. He also incorporates more jazz into his act, and pursues bookings at casinos, where the money is even better. His business enterprises flourish; he purchases radio stations noting, "I used to shine shoes in front of radio stations, now I own radio stations. His influence is such that when he plays the Boston Garden the day after the assassination of Martin Luther King, he persuades a local TV station to film and re-run the concert throughout the night to keep people from rioting. Boston is the only major city in America that stays calm. The apex of such social consciousness is his 1968 single "Say It Loud (Im Black and Im Proud), which reverberates around North America and the world. He is elevated to hero status in Brazil and throughout Africa. Brown is at the crossroads of Vegas aspirations and influence from black militants like H. Rap Brown. With fans rushing the stage everywhere he goes, Brown himself is unsure of the message, as witnessed in a live recording in Dallas from the summer of 1968. Leeds recalls that, "It was a time when he was under pressure from his black audience to retain that presence because he had been anointed as the spokesperson for a certain class of black youth in America. It was the axis of his fan base, and at the same time he coveted crossover acceptance and his ultimate goal was to become an entertainer for all people which he eventually became, of course. He was walking a very thin line to appease both. I dont know if anyone else could have pulled it off. He travels to Vietnam to entertain the troops in 1968 with a white bassist, Tim Drummond though back home, certain factions are not pleased that Drummond is "taking a black mans job. Upon his return, he fills Yankee Stadium, although he is distraught that the show is broken up by overzealous fans; Leeds notes "the old Southern patriarch in James Brown saw it much like the police did: you stupid kids are trashing the show; I came to entertain you! His activities this year garner him dinner at the White House. Upon receiving an invitation to Vice President Hubert Humphreys table, he refuses, stating "Im not the VPs boy. If he wants to meet me halfway, thats fine. Hits in this period become ever funkier: "I Got The Feeling, "Mother Popcorn and "Give It Up Or Turnit-a Loose are all number one hits, test marketed on his radio stations, and broken nationally by his never-ending tours. More changes in the band bring bassist Sweet Charles and the departure of Ellis in early 1969.

1970 to 1971

Brown is a tyrant with his band, fining them for missed notes and unkempt uniforms, withholding their pay to keep them in line, and calling marathon rehearsals just to tire them out and take the fight out of them. His band has stayed with him for years out of fear that they were at the peak of their careers and Brown would interfere with subsequent employment opportunities. The band is also mesmerised by easy sex and drug access on the road. But money is the number one gripe. In his autobiography, Wesley notes, "I figured out that James could make anywhere from $350,000 to $500,000 a week but his payroll remained at about a paltry $6,000 a week. And he acted like he didnt want to give you that. Finally, the band gives Brown an ultimatum before a gig in Columbus, Georgia in March 1970, which Brown rejects. Right hand man Byrd is given the task of shuttling one of Kings session bands to the gig via the Lear jet. The group, named the Pacesetters, features a 19-year-old Bootsy Collins and his brother Phelps. They walk into the venue just as the Orchestra is walking out. They unit gels on stage immediately; two months later they cut "Sex Machine, which trades the polyrhythms of the late 60s Orchestra into the hard funk that would define the newly christened JBs. An African influence creeps in with hand drummer Johnny Griggs joining the band, and becomes more prominent when Brown tours Nigeria in 1970, spending an eye-opening evening at Fela Kutis Afrospot. Bootsy and Catfish inject a youthful abandon to Browns music, which becomes more elastic on the bottom with Bootsys virtuosity, and acid-tinged throughout with Catfishs wailing Hendrix-meets-John Lee Hooker solos. While cutting the classics "Super Bad and "Soul Power, acid literally becomes more than a tinge in the music the Collins brothers become full-on freaks, though Brown is unaware. They leave the band after a gig in spring 1971 during which Collins, tripped out on stage, imagines his bass has turned into a snake. Undaunted, Brown recruits a new set of JBs under the direction of Fred Wesley. This coincides almost exactly with his departure from King Records for Dutch record label Polydor, who are seeking to crack the American market. In a prescient move, Browns catalogue goes with him only Ray Charles had ever undertaken a similar move. The first release of the new JBs and on Polydor is the million selling "Hot Pants.

1971 to 1976

Despite Browns protestations that Polydor doesnt have a clue about what to do with his records, Leeds states "nobody influenced what he was recording in the early days of the Polydor deal, he was still randomly booking studios whenever and wherever he wanted to, and doling out to them the records he wanted released. I dont think they had any influence until the sales started to slow down. Due to the changing marketplace, Brown recording sessions focus more on albums. He also starts up People Records, not his first label, but by far his most successful, with substantial hits by the JBs and backup vocalist Lyn Collins. His band is anchored by the rock solid blues shuffle of drummer John "Jabo Starks. Leeds opines that technically, the 70s band was inferior: "With that band in the 70s he just dummied down the parts. With James Brown you can write rhythmic horn charts that dont require chops but still sound effective. Thats what Fred [Wesley] was doing. He was brilliant at doing that and obscuring thats what it was. Still racking up the hits and expanding his business ventures through 1972, Brown controversially endorses Richard Nixons bid for a second term, which results in his shows at the Apollo being picketed. In 1973, after having finished work on his first soundtrack, Black Caesar, his eldest son Teddy is killed in a car accident. Devastated, he slowly begins to ease up on his workload. Nevertheless, the show goes on, and he continues to produce quality singles including the JBs smash "Doing It To Death which sees Maceo Parker rejoin the band, and "The Payback. He also continues to play important shows, such as the Ali-Foreman Rumble in the Jungle in Zaire documented in When We Were Kings. Around this time, Browns longevity starts to become part of his image when New York DJ Rocky G dubs him "The Godfather of Soul. By 1975, his records are declining in originality and the IRS comes down on him for back taxes and a payola investigation involving his personal manager Charles Bobbit. He sinks a considerable amount of money into a Soul Train-like show called Future Shock, which never makes it out of Georgia. As Brown becomes more and more embroiled in his legal and financial troubles, his band mutinies once again. Leeds notes: "There was a lot of loyalty to Fred Wesley that overcame a lot of things that could have been problems with the band. He was the perfect MD for that band. He had the personality to earn the respect of all the musicians, because the band was in a couple of cliques you had the younger guys who werent really of the same calibre as the established guys, but Fred was equally respected by everyone in the group and became sort of an umbrella figure who didnt allow the cliques to become too separate. It really didnt fall apart until after he left, around 75, and it very quickly fell apart after that. In addition, says Leeds: "Business had slowed down on the road, his overexposure on the arena circuit had caught up with him. After playing these cities twice a year for more than a decade it had finally gotten to the point where it was like Oh, him again? Parker, Wesley and 60s JB survivor Kush Griffith join Bootsy in Parliament-Funkadelic, where they become known as the Horny Horns.

1976 to 1980

Brown continues to release album after album for Polydor but cannot score beyond the lower reaches of the R&B charts now dominated by disco and funk of a much slicker variety than JB can muster. One bright spot artistically is "The Original Disco Man from 1979, featuring Muscle Shoals musicians under the direction of Brad Shapiro (Millie Jackson, Wilson Pickett). He finally leaves Polydor in 1980 and cuts a quick LP in Florida to be released on old friend Henry Stones TK label. "Rapp Payback is a middling hit on the R&B chart. At the same time, he joins other soul legends in the hit movie The Blues Brothers, which ensures that his tours, now scaled back to discos and nightclubs from the arenas he used to do, still pull in decent cash.

1981 to 1991

He appears in another Dan Aykroyd movie, Doctor Detroit, in 1983. He is without a label for several years, with a potential deal with Island Records scuttled by a disastrous session with reggae riddim kings Sly and Robbie. The self-released "Bring it On the same year is followed by a one-off project with hip-hop pioneer Afrika Bambataa entitled "Unity. This is the last truly satisfying record Brown would ever make, but points to his enduring influence on hip-hop. The solo drum sections of his late 60s to early 70s output have become the underpinnings of this new music, and breakdancing is reputed to have started with 1972s "Get On the Good Foot. In 1985 his first CD collection, The CD of JB, introduces him to a new generation of fans. Even more importantly, his appearance in Rocky IV leads to his biggest pop hit in 20 years, the much-maligned "Living in America. In 1986, he is inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. His autobiography is released the following year. Around this time, with all his original material out of print, Polydor begins assembling tracks into well-annotated, historically themed compilations. Seven-inch singles are expanded into their full studio takes to display the full majesty of his band. Some ten comps, including vital collections of the People years, become a library for the new art of sampling, and the James Brown snare sounds of the 60s and 70s become synonymous with old school hip-hop. Unfortunately, around this time, his personal life becomes a shambles. His wife Adrienne introduces him to PCP, and leads to a series of increasingly odd public appearances. In September 1988, doped up and carrying a shotgun, he enters an insurance seminar next to his Augusta office. He is said to have asked seminar participants if they were using his private restroom. Police chased Brown for half an hour before shooting out the tires of his truck. He spends 25 months in jail and is paroled in February1991.

1991 to 2006

Upon his release from prison, a revitalized JB, sounding better than in years, takes the stage at the Wiltern Theatre in Los Angeles for a pay per view concert featuring MC Hammer, Bell Biv Devoe, C + C Music Factory, Kool Moe Dee and En Vogue. Financially depleted from years of litigation and continued IRS garnishment, he hits the road yet again playing more than 200 nights a year to ever bigger ticket prices. The band consists of some old faces like Sweet Charles on keys, and Fred Thomas, bassist for the JBs Mark 2. Far removed from their trendsetting funk days, a JB show continues to be great value for the money. Still in full command of his phrasing, even as his vocal range shrinks, he can still drive the band with precision. Albums are basically a thing of the past. His contract with Scotti Brothers, his label since the "Living in America days, ends in 1993. Despite off and on recording, very little finished product surfaces: his final album is 2002s Next Step. While he is basically sober after his prison stint, he relapses in 1998 and spends a 90-day stint in rehab. In 1999 he finally becomes financially solvent when he converts his future royalties into $30 million in bonds, through the same firm David Bowie had worked with. Finally collecting the accolades of a long and hard-fought career, JB embarks on his Seven Decades of Funk tour in 2004, only to be laid up by prostate cancer. Surgery is successful, and he resumes his activities, publishing a second autobiography in 2005, entitled I Feel Good: A Memoir of a Life of Soul. Although increasingly plagued with arthritis, JB seems in reasonable health in late 2006 when he enters hospital for pneumonia. Suddenly in the early hours of Christmas morning, he passes away, as long-time confidant Rev. Al Sharpton noted, "He was dramatic to the end dying on Christmas Day.