A few months ago, I noticed a brand new James Brown compilation on the Dusty Groove America homepage, James Browns Funky Peoples Greatest Breakbeats. "This long-overdue set brings together 16 key numbers from the best late 60s/early 70s James Brown years in the studio. The sets got a special focus on tracks that have been used as samples by hip-hoppers a fact thats well documented and cross-referenced in the notes but the real appeal to our ears is to have so many great funky tracks brought together in one place, all legitimate, and nearly all of them in their full extended versions.

This "new reissue is a re-compilation of two late 80s compilations of second tier James Brown that delved beyond the hits, this time in a hip-hop context. Thats just one arena in which original 60s and 70s funk and soul has been repackaged, reissued and recontextualised in ways that continue to redefine its relevance to contemporary music. Whether its sampled as breakbeats, mixed into DJ sets, resold as baby boomer nostalgia or treasured as a holy grail of crate-digging connoisseurs, vintage soul and funk has journeyed from of-the-moment sounds into the realm of timeless for several generations of music lovers. From singles to compilations to samples back to compilations, the sound of the original recordings is creating ever-louder echoes of the echo.

Soul and funk of the 60s and 70s had an incalculable influence on American and global popular music. Unlike rock, Americas other great post-war musical phenomenon, soul music came from specifically Afro-American cultural experiences. Its impulses included gospel and jazz, increasing rhythmic sophistication and a broader instrumental palette. Its national successes (James Brown, Sly Stone, Stevie Wonder, Isaac Hayes) expanded the artistic and commercial dreams of these soul purveyors, but for the huge majority, soul music was a regional industry: recorded by local artists, pressed on 45s, distributed through "mom & pop stores and played almost exclusively in regional radio markets. With no national distribution or support, many recordings disappeared not long after their initial release; almost as soon as the "golden age of soul came to an end these recordings were valued by collectors and aficionados, whose dedication helped keep the music alive.

They were the original "crate-diggers, a term that would never have found traction in the modern lexicon if it werent for hip-hop. Early rap producers latched onto vintage soul and funk as well as other tracks from the unknown to the mainstream for their breakbeats. DJs would take two copies of the same record and play the solo rhythm breaks, over which MCs would rap. As hip-hop evolved, how choice (which soon came to mean how obscure) your breaks were went a long way to defining your sound. In the birthplace of hip-hop, New York City, the pursuit of more obscure records became increasingly competitive. The phenomenon spawned a market for a new type of compilation devoted entirely to breaks.

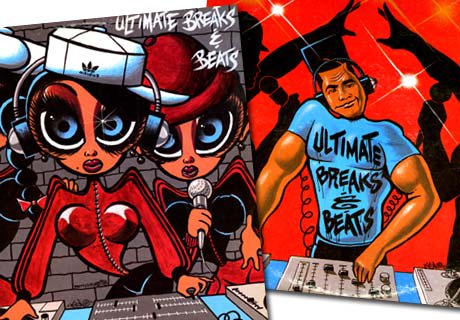

Rick Wojcik, buyer for online groove merchant Dusty Groove America, explains the origin of the now legendary Ultimate Breaks and Beats series. "It was started by a guy named Lenny Roberts, a chauffeur who lived in the South Bronx. When hip-hop started, he watched all these DJs go nuts for records. He was a bit of a collector himself, so he started tracking down and selling original copies. He got so many requests for certain tracks, he started putting together these compilations. He put all the songwriting credits and publishing information on them and publishers are far more strict about following up than record companies, because publishing is all these people have. In order to maintain his taste-making credibility (and his corner of the breaks market), he wouldnt list the artists. "But back in the old days, Wojcik says, "he would give you a printed list if you requested it. A hand-typed list.

More than simply making obscure music available again, according to Wojcik, "UBB was establishing a new genre. I remember going to the Record Factory in New York, which was a big outlet for those records, and they had a section up front called breaks. Theyd have a Foreigner record next to a Cat Stevens record next to an Incredible Bongo Band record. They sold breaks it wasnt even about the songs. Thats an understatement. Even the most soulless dreck like John Cougars "Jack and Diane and Billy Squiers "Big Beat coexisted with timeless funk like James Browns "Funky President and influential non-hits like Babe Ruths "The Mexican; they all acquired funk credentials in the new context of hip-hop.

The entrepreneurial Roberts represents a crossroads for the second coming of funk and soul. His collections helped demolish genre classifications the only qualification was their breaks. It gave new life to both known productions and total obscurities. And he represents the taste-making "music concierge, a midwife who single-handedly influenced and helped give rise to an emerging, wholly original art form.

Quickly, Ultimate Breaks and Beats helped spearhead a crate-digging habit that for some has become a lifestyle. In The Face in 1988, uber-sampler Steinski profiled the scene at now-defunct Times Square retailer Downstairs Records. Owner Stanley Platzer recounted: "Well, the Salt-N-Pepa girls were in, and they bought every [UBB comp], Volumes 1 to 12; their LP had them all on there. [Run DMC DJ] Jam Master Jay bought four of each about three weeks ago.

After years of sampling in hip-hop, newer school producers and fans picked up the torch of crate-digging, quickly moving past the initially fertile ground of UBB, James Brown and Parliament-Funkadelic into more obscure music. Nav Sangha, aka Dee Jay Nav, co-owner of Torontos Play De Record, agrees. "Most hip-hop producers that have stopped by our shops have proven to be avid collectors. DJ Premier and Madlib always spend some time digging for original sample material.

Even if sampling has declined in importance for hip-hop, its producers, DJs and a sizable number of its fans still value the crate-digging ethos and the increasingly esoteric, regional and wonderful music it yields. Through the efforts of these opinion leaders, the search for soul has thoroughly exhumed American soul and has moved on to other funky music around the world, broadening the definition of "soul in the process.

In the UK, soul reissues were initially unrelated to hip-hop, but very much in keeping with subcultures specific to Britain. At the beginning of the 80s, legendary DJ Norman Jay started a sound system called Good Times, playing 70s soul, funk and disco at the traditionally Caribbean-oriented Notting Hill Carnival in London. Initially a tough sell, his style found a large audience that included Northern Soul lovers, jazz dancers and Latin aficionados. Charly Records, already an established reissue label for jazz and blues, was very active during that period producing vinyl compilations to cater to this audience, featuring everything from the Meters to Ray Barretto to Joe Tex. This underground was well represented by the founding of KISS FM pirate radio in 1985, where Jay hosted his Original Rare Groove Show, and "rare groove became the term associated with cuts he played. Up and comer Gilles Peterson, another KISS FM DJ, had a similar experience with the fledgling Acid Jazz label; their initial releases, almost all compilations, tended to feature context-related inspirational oldies alongside new cuts.

Nav notes that this cross-genre UK approach was similar to how "disco and "breaks in the States were originally hodgepodges of different types of beat-oriented music. "The early Mod and Northern Soul scenes are an example of how music from various genres could all collide. This happened in the early days of DJ culture in the U.S. Pioneering New York DJs like Walter Gibbons, Larry Levan and David Mancuso did not have crates of records from some obscure subgenre at the same BPM to work with, so they just played a bit of everything that fit their vibe.

DJs and independent labels helped lead the revival of 60 and 70s funk and soul, but it remained a vinyl market. Increasingly, buyouts of smaller companies by major labels meant that large corporations held very valuable parts of this music in their catalogues but initially didnt move beyond greatest hits packages by established name artists. That began to change in the early 80s with comps like Columbia Legacys Lost Soul (though primarily targeted to a traditional R&B audience instead of a crossover one). But the success of soundtrack-driven films like The Blues Brothers and particularly The Big Chill, pointed to a new market for this music: aging baby boomers. The Big Chill, released in 1983, associated white ex-hippies with the soundtracks Motown classics (to Berry Gordys dismay); it pointed to a new market beyond its Afro-American base and outside of hip-hop sample culture. And technology, in the form of the CD, paved that highway.

This "boomer market for soul music was both affluent and were early adopters of the CD. Remastering and repackaging back catalogue provided a high profit margin, and the CD format offered amazing potential to showcase a greater breadth of material in a sonically superior format.

In this incredibly profitable marketplace, limitation quickly gave way to innovation. Complaints about CD artwork soon birthed elegant box sets that took advantage of longer potential play times with bonus tracks and alternate takes. Quickly, these sets were being housed with scholarly liner notes that explored key historical context and analysis that helped further the understanding of where this music came from.

Funk and soul came from a singles world, found new life in cut-up snippets and extended compilations, and now through the digital download, it seems the music industry is moving back to a singles approach. But the digital realm can seem like the worlds largest warehouse of 45s: heavy on selection but light on direction. Rather than the death knell for CDs, the well-curated compilation, with appropriate context and historical insight, will remain a cornerstone for this music, a lesson labels are learning.

Early attempts at catalogue-raiding compilations were fairly straightforward, like jazz label Blue Notes Blue Break Beats series, revisioning mainstream soft jazz that became influential in the trip-hop, acid jazz and "jazzy groove context. Suddenly, the multiplicity of CD collections reconstructed stories well worth telling, bringing to light points of view that dug well beyond established hits packages by known superstars. History was no longer just being written by the victors.

The Soul Sides audio blog, run by music journalist and professor of sociology Oliver Wang, represents another new life for this music. The site is akin to an ongoing reissue project, providing on a track-by-track basis scholarly analysis and thematic annotation. It also resulted in a Soul Sides compilation released a few months ago. "I looked at the songs posted on the blog during its life, and wanted half the songs to be drawn from that. I though it was good continuity that it should nod back to the site.

"A good comp should try to be education, Wang says. "Not so much to tell the listener what they should be getting out of it, but perhaps what they should be thinking about. Its very rare that I talk about music in strictly a sonic sense without talking about the larger world it comes out of historically and geographically.

Wang represents a key component to what has kept this music current, but sees the move to a single-track download as inevitable. "What were seeing now is much more focused on songs being downloaded not to repeat the whole the album is dead mantra but its kind of hard to argue that its not.

Yet this confirms the ongoing relevance of the DJ. There will always be a demand for musical concierges; it takes a dedicated individual to navigate the sheer number of musical choices available today. The role of the DJ has moved beyond crate-digging and into the role of contextualiser. Even satellite radios best experiences are guided by personalities, not simply a continuous flow of genre-specific music. An individuals unique sensibility is irreplaceable in creating a memorable musical experience to create something that is greater than the sum of its parts. Even a retail environment, like the carefully worded blurbs that grace Dusty Grooves ten thousand titles, can be examples of musical aggregation. Wojcek underlines the continuing appeal of music as a physical object, acknowledging his bias along the way: "With new media its always a question of signal to noise. Apples got iTunes, but theres so much music on there, if youre looking for direction maybe its better to spend $15 on a hard copy CD. Were dealing with history here and history has all of these aesthetics. That has yet to be proven with many of the new media out there.

The well-annotated compilation will not disappear with the click of a mouse. It initially made out-of-print music available again, recontexualised it as samples and for the dance floor, put it into a larger historical context and reintroduced it to generation after new generation. The crate digging ethos has helped put obscure artists on the same plane as the original superstars. As for the continued popularity of soul music, Wang surmises: "I dont know if its ever going to abate. Even the kids raised on this music are still fascinated with it because theres really something important. Some kinds of music really are timeless.

Comps I've Known and Loved

These three favourites from my early years of beat collecting each established benchmarks in their own way.

Urban Classics (Polygram, 1987)

Urban Classics, the first of three volumes, is a fine snapshot of the sound of London. Side one is all James Brown rarities (at the time) and featured tracks that were barely a decade old like "Blow Your Head and "Dont Tell It, which became much less obscure after being sampled in "Public Enemy #1 and "Poetry by Boogie Down Productions. Side two was a mix of stepping soul, jazzy grooves and ballads including Roy Ayers "Everybody Loves the Sunshine: still Camden Towns unofficial anthem after 30 years. This compilation was a soundtrack to a hip, culturally aware lifestyle, one of the first of its kind.

James Brown Motherlode (Polygram, 1989)

Some maintain that Brown wasnt as big a crossover success in the 70s as the 60s because of the unfamiliarity of Hollands Polygram records with the U.S. market. By the end of the 80s, the company had cut and pasted JBs recorded legacy into ten top-notch compilations without reissuing any of his original albums. Motherlode was the icing on the cake, almost entirely composed of unheard James Brown. Top notch stuff, too "Shes the One became a top ten hit in Britain upon this albums release. As with most of the JB collections of this era, Cliff Whites enthusiastic liner notes were part scholar, part hepcat. In years to come, it was far more common to find lost tracks, albums or even ingredients for final mixes (Miles Davis, the Beatles) to be released as separate anthologies this was a sign of fans maturing tastes and the usefulness of the CD format to expand the appreciation of the repertoire.

Brazilica! (Talkin Loud, 1994)

Brazilian musics popularity in Europe and North America has waxed and waned since the 30s; this compilation was largely responsible for an upswing during the 90s that continues to grow. Gilles Peterson has had a knack for reissues over his long career, but none was better, or more influential than this quirky but well considered survey of bossa, MPB and fusion grooves of the 60s and 70s. Reintroducing artists such as Jorge Ben, Joyce, the Tamba Trio and Baden Powell to a new generation, the selection of music here demonstrated that tropical soul and jazz could work on a dance floor alongside contemporary beats.

This "new reissue is a re-compilation of two late 80s compilations of second tier James Brown that delved beyond the hits, this time in a hip-hop context. Thats just one arena in which original 60s and 70s funk and soul has been repackaged, reissued and recontextualised in ways that continue to redefine its relevance to contemporary music. Whether its sampled as breakbeats, mixed into DJ sets, resold as baby boomer nostalgia or treasured as a holy grail of crate-digging connoisseurs, vintage soul and funk has journeyed from of-the-moment sounds into the realm of timeless for several generations of music lovers. From singles to compilations to samples back to compilations, the sound of the original recordings is creating ever-louder echoes of the echo.

Soul and funk of the 60s and 70s had an incalculable influence on American and global popular music. Unlike rock, Americas other great post-war musical phenomenon, soul music came from specifically Afro-American cultural experiences. Its impulses included gospel and jazz, increasing rhythmic sophistication and a broader instrumental palette. Its national successes (James Brown, Sly Stone, Stevie Wonder, Isaac Hayes) expanded the artistic and commercial dreams of these soul purveyors, but for the huge majority, soul music was a regional industry: recorded by local artists, pressed on 45s, distributed through "mom & pop stores and played almost exclusively in regional radio markets. With no national distribution or support, many recordings disappeared not long after their initial release; almost as soon as the "golden age of soul came to an end these recordings were valued by collectors and aficionados, whose dedication helped keep the music alive.

They were the original "crate-diggers, a term that would never have found traction in the modern lexicon if it werent for hip-hop. Early rap producers latched onto vintage soul and funk as well as other tracks from the unknown to the mainstream for their breakbeats. DJs would take two copies of the same record and play the solo rhythm breaks, over which MCs would rap. As hip-hop evolved, how choice (which soon came to mean how obscure) your breaks were went a long way to defining your sound. In the birthplace of hip-hop, New York City, the pursuit of more obscure records became increasingly competitive. The phenomenon spawned a market for a new type of compilation devoted entirely to breaks.

Rick Wojcik, buyer for online groove merchant Dusty Groove America, explains the origin of the now legendary Ultimate Breaks and Beats series. "It was started by a guy named Lenny Roberts, a chauffeur who lived in the South Bronx. When hip-hop started, he watched all these DJs go nuts for records. He was a bit of a collector himself, so he started tracking down and selling original copies. He got so many requests for certain tracks, he started putting together these compilations. He put all the songwriting credits and publishing information on them and publishers are far more strict about following up than record companies, because publishing is all these people have. In order to maintain his taste-making credibility (and his corner of the breaks market), he wouldnt list the artists. "But back in the old days, Wojcik says, "he would give you a printed list if you requested it. A hand-typed list.

More than simply making obscure music available again, according to Wojcik, "UBB was establishing a new genre. I remember going to the Record Factory in New York, which was a big outlet for those records, and they had a section up front called breaks. Theyd have a Foreigner record next to a Cat Stevens record next to an Incredible Bongo Band record. They sold breaks it wasnt even about the songs. Thats an understatement. Even the most soulless dreck like John Cougars "Jack and Diane and Billy Squiers "Big Beat coexisted with timeless funk like James Browns "Funky President and influential non-hits like Babe Ruths "The Mexican; they all acquired funk credentials in the new context of hip-hop.

The entrepreneurial Roberts represents a crossroads for the second coming of funk and soul. His collections helped demolish genre classifications the only qualification was their breaks. It gave new life to both known productions and total obscurities. And he represents the taste-making "music concierge, a midwife who single-handedly influenced and helped give rise to an emerging, wholly original art form.

Quickly, Ultimate Breaks and Beats helped spearhead a crate-digging habit that for some has become a lifestyle. In The Face in 1988, uber-sampler Steinski profiled the scene at now-defunct Times Square retailer Downstairs Records. Owner Stanley Platzer recounted: "Well, the Salt-N-Pepa girls were in, and they bought every [UBB comp], Volumes 1 to 12; their LP had them all on there. [Run DMC DJ] Jam Master Jay bought four of each about three weeks ago.

After years of sampling in hip-hop, newer school producers and fans picked up the torch of crate-digging, quickly moving past the initially fertile ground of UBB, James Brown and Parliament-Funkadelic into more obscure music. Nav Sangha, aka Dee Jay Nav, co-owner of Torontos Play De Record, agrees. "Most hip-hop producers that have stopped by our shops have proven to be avid collectors. DJ Premier and Madlib always spend some time digging for original sample material.

Even if sampling has declined in importance for hip-hop, its producers, DJs and a sizable number of its fans still value the crate-digging ethos and the increasingly esoteric, regional and wonderful music it yields. Through the efforts of these opinion leaders, the search for soul has thoroughly exhumed American soul and has moved on to other funky music around the world, broadening the definition of "soul in the process.

In the UK, soul reissues were initially unrelated to hip-hop, but very much in keeping with subcultures specific to Britain. At the beginning of the 80s, legendary DJ Norman Jay started a sound system called Good Times, playing 70s soul, funk and disco at the traditionally Caribbean-oriented Notting Hill Carnival in London. Initially a tough sell, his style found a large audience that included Northern Soul lovers, jazz dancers and Latin aficionados. Charly Records, already an established reissue label for jazz and blues, was very active during that period producing vinyl compilations to cater to this audience, featuring everything from the Meters to Ray Barretto to Joe Tex. This underground was well represented by the founding of KISS FM pirate radio in 1985, where Jay hosted his Original Rare Groove Show, and "rare groove became the term associated with cuts he played. Up and comer Gilles Peterson, another KISS FM DJ, had a similar experience with the fledgling Acid Jazz label; their initial releases, almost all compilations, tended to feature context-related inspirational oldies alongside new cuts.

Nav notes that this cross-genre UK approach was similar to how "disco and "breaks in the States were originally hodgepodges of different types of beat-oriented music. "The early Mod and Northern Soul scenes are an example of how music from various genres could all collide. This happened in the early days of DJ culture in the U.S. Pioneering New York DJs like Walter Gibbons, Larry Levan and David Mancuso did not have crates of records from some obscure subgenre at the same BPM to work with, so they just played a bit of everything that fit their vibe.

DJs and independent labels helped lead the revival of 60 and 70s funk and soul, but it remained a vinyl market. Increasingly, buyouts of smaller companies by major labels meant that large corporations held very valuable parts of this music in their catalogues but initially didnt move beyond greatest hits packages by established name artists. That began to change in the early 80s with comps like Columbia Legacys Lost Soul (though primarily targeted to a traditional R&B audience instead of a crossover one). But the success of soundtrack-driven films like The Blues Brothers and particularly The Big Chill, pointed to a new market for this music: aging baby boomers. The Big Chill, released in 1983, associated white ex-hippies with the soundtracks Motown classics (to Berry Gordys dismay); it pointed to a new market beyond its Afro-American base and outside of hip-hop sample culture. And technology, in the form of the CD, paved that highway.

This "boomer market for soul music was both affluent and were early adopters of the CD. Remastering and repackaging back catalogue provided a high profit margin, and the CD format offered amazing potential to showcase a greater breadth of material in a sonically superior format.

In this incredibly profitable marketplace, limitation quickly gave way to innovation. Complaints about CD artwork soon birthed elegant box sets that took advantage of longer potential play times with bonus tracks and alternate takes. Quickly, these sets were being housed with scholarly liner notes that explored key historical context and analysis that helped further the understanding of where this music came from.

Funk and soul came from a singles world, found new life in cut-up snippets and extended compilations, and now through the digital download, it seems the music industry is moving back to a singles approach. But the digital realm can seem like the worlds largest warehouse of 45s: heavy on selection but light on direction. Rather than the death knell for CDs, the well-curated compilation, with appropriate context and historical insight, will remain a cornerstone for this music, a lesson labels are learning.

Early attempts at catalogue-raiding compilations were fairly straightforward, like jazz label Blue Notes Blue Break Beats series, revisioning mainstream soft jazz that became influential in the trip-hop, acid jazz and "jazzy groove context. Suddenly, the multiplicity of CD collections reconstructed stories well worth telling, bringing to light points of view that dug well beyond established hits packages by known superstars. History was no longer just being written by the victors.

The Soul Sides audio blog, run by music journalist and professor of sociology Oliver Wang, represents another new life for this music. The site is akin to an ongoing reissue project, providing on a track-by-track basis scholarly analysis and thematic annotation. It also resulted in a Soul Sides compilation released a few months ago. "I looked at the songs posted on the blog during its life, and wanted half the songs to be drawn from that. I though it was good continuity that it should nod back to the site.

"A good comp should try to be education, Wang says. "Not so much to tell the listener what they should be getting out of it, but perhaps what they should be thinking about. Its very rare that I talk about music in strictly a sonic sense without talking about the larger world it comes out of historically and geographically.

Wang represents a key component to what has kept this music current, but sees the move to a single-track download as inevitable. "What were seeing now is much more focused on songs being downloaded not to repeat the whole the album is dead mantra but its kind of hard to argue that its not.

Yet this confirms the ongoing relevance of the DJ. There will always be a demand for musical concierges; it takes a dedicated individual to navigate the sheer number of musical choices available today. The role of the DJ has moved beyond crate-digging and into the role of contextualiser. Even satellite radios best experiences are guided by personalities, not simply a continuous flow of genre-specific music. An individuals unique sensibility is irreplaceable in creating a memorable musical experience to create something that is greater than the sum of its parts. Even a retail environment, like the carefully worded blurbs that grace Dusty Grooves ten thousand titles, can be examples of musical aggregation. Wojcek underlines the continuing appeal of music as a physical object, acknowledging his bias along the way: "With new media its always a question of signal to noise. Apples got iTunes, but theres so much music on there, if youre looking for direction maybe its better to spend $15 on a hard copy CD. Were dealing with history here and history has all of these aesthetics. That has yet to be proven with many of the new media out there.

The well-annotated compilation will not disappear with the click of a mouse. It initially made out-of-print music available again, recontexualised it as samples and for the dance floor, put it into a larger historical context and reintroduced it to generation after new generation. The crate digging ethos has helped put obscure artists on the same plane as the original superstars. As for the continued popularity of soul music, Wang surmises: "I dont know if its ever going to abate. Even the kids raised on this music are still fascinated with it because theres really something important. Some kinds of music really are timeless.

Comps I've Known and Loved

These three favourites from my early years of beat collecting each established benchmarks in their own way.

Urban Classics (Polygram, 1987)

Urban Classics, the first of three volumes, is a fine snapshot of the sound of London. Side one is all James Brown rarities (at the time) and featured tracks that were barely a decade old like "Blow Your Head and "Dont Tell It, which became much less obscure after being sampled in "Public Enemy #1 and "Poetry by Boogie Down Productions. Side two was a mix of stepping soul, jazzy grooves and ballads including Roy Ayers "Everybody Loves the Sunshine: still Camden Towns unofficial anthem after 30 years. This compilation was a soundtrack to a hip, culturally aware lifestyle, one of the first of its kind.

James Brown Motherlode (Polygram, 1989)

Some maintain that Brown wasnt as big a crossover success in the 70s as the 60s because of the unfamiliarity of Hollands Polygram records with the U.S. market. By the end of the 80s, the company had cut and pasted JBs recorded legacy into ten top-notch compilations without reissuing any of his original albums. Motherlode was the icing on the cake, almost entirely composed of unheard James Brown. Top notch stuff, too "Shes the One became a top ten hit in Britain upon this albums release. As with most of the JB collections of this era, Cliff Whites enthusiastic liner notes were part scholar, part hepcat. In years to come, it was far more common to find lost tracks, albums or even ingredients for final mixes (Miles Davis, the Beatles) to be released as separate anthologies this was a sign of fans maturing tastes and the usefulness of the CD format to expand the appreciation of the repertoire.

Brazilica! (Talkin Loud, 1994)

Brazilian musics popularity in Europe and North America has waxed and waned since the 30s; this compilation was largely responsible for an upswing during the 90s that continues to grow. Gilles Peterson has had a knack for reissues over his long career, but none was better, or more influential than this quirky but well considered survey of bossa, MPB and fusion grooves of the 60s and 70s. Reintroducing artists such as Jorge Ben, Joyce, the Tamba Trio and Baden Powell to a new generation, the selection of music here demonstrated that tropical soul and jazz could work on a dance floor alongside contemporary beats.