Sunday afternoon outside the Cameron House, one of the long-established hip hang-out spots on Toronto's Queen Street West, kids pass by with headphones blasting and eyes scanning for the latest fashions. They are oblivious to the fact that inside the bar, the clock is turned back to the 1940s as the Backstabbers, one of the city's best bluegrass bands, plays a weekly gig. Dressed in vintage suits and sharing a single microphone, they certainly look the part of Depression-era minstrels. They sound like it too, with high harmonies that recall the great brother duos of the time: the Stanleys, the Louvins, the Delmores.

But listen more closely; it's apparent that this isn't just a representation of a mythical America that no one in the room can honestly say they have experienced - local Toronto locales get name-dropped regularly in the Backstabbers' original tunes. "I think it always comes back to bluegrass being a reflection of the community," mandolinist "Colonel" Tom Parker says. "We're not going to write songs about working in coal mines. We're living in Toronto, so we're going to write about what's going on around us. But the emotions behind the songs never change, and that's what will always keep people interested in bluegrass."

It's a dilemma that is not uncommon to most genres of music: purists versus progressives. But bluegrass, with its uniquely regional image (the rural South), and the fact that it is the invention of one man (Bill Monroe), has been faced with this conflict since Monroe and his Blue Grass Boys put out their first record.

In Canada, bluegrass has existed on an even shakier foundation. Although many parts of the country share similar cultural roots, it's perceived as a purely American form. While that has hindered Canada in developing a national bluegrass community, a new batch of young musicians - be they Vancouver's Zubot and Dawson, Winnipeg's the Duhks or Ottawa's Greenfield Main - are adding their own personal stamp. Interpretations from this new generation have meant not playing by the rules, which during Monroe's lifetime, was heresy.

"Bluegrass," according to Monroe's stringently held guidelines, is strictly defined by its instrumentation: mandolin, banjo, fiddle, guitar, upright bass and group harmonies. Like Henry Ford upgrading from four-cylinders to V8's, in the 1940s, Monroe and his Blue Grass Boys took "old time" string band music and added a driving rhythmic kick that relied heavily on the virtuosity of his musicians, most notably banjo player Earl Scruggs, whose blinding technique redefined the instrument. It was also music that stayed true to the values of family, religion, and hard work. Like a jazz bandleader, Monroe pushed his players' talents to their physical limit; in terms of energy and group interaction, he foreshadowed rock'n'roll. (It's no coincidence that the flip side of Elvis Presley's first single was his version of Monroe's "Blue Moon of Kentucky.")

Since Monroe's time (his career continued until his death in 1996), bluegrass and other "old time" acoustic music enjoyed a thriving, if unheralded, place in the lives of music lovers. But it was only the shocking success of the O Brother Where Art Thou? soundtrack that swung the spotlight toward it. Breakthroughs like that are impossible to predict, but an emphasis on innovation usually provides the best chance to reach wider audiences.

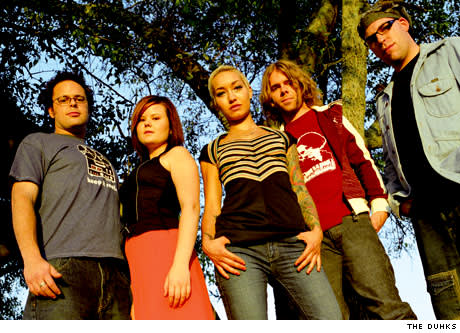

This year's biggest breakthrough belongs to Winnipeg's the Duhks, who, after landing a deal for their self-titled debut album on the venerable American roots label Sugar Hill, are spending the rest of the year touring everywhere except their homeland. Formed in 2002 by banjo player Len Podolak, whose parents were among the original organisers of the Winnipeg Folk Festival, the Duhks represent a youthful naivety toward old time music, not relying so much on virtuosity, but on throwing any influence they can into the mix and topping it off with a punky attitude.

"Our main intention when we started was to get people to dance," Podolak says. "All this music that we love and that's part of our sound - bluegrass, Irish music, French-Canadian music, Afro-Cuban music - it's all really distinct, but it's all related. A lot of the instrumentation is similar, like the fiddle, so what people are responding to is hearing all of these different influences, but we're not forcing it. We're just playing our instruments the way we know how."

On The Duhks, the band tackles everything from the folk standard "The Wagoner's Lad," to Leonard Cohen's "Everybody Knows." Growing up within the folk festival environment is what Podolak credits for erasing any barriers he had when it came to playing music. "My original intention was to play an updated version of old time music, but once we got the line-up solidified, we became this collective, sharing so many different styles. I got to see so many amazing performers at the festival when I was a kid that it's never really crossed my mind to limit myself to a certain sound. The banjo isn't a traditional Irish instrument, but that's never stopped me from playing those melodies."

Podolak's open-mindedness seems in keeping with Canada's general attitude toward bluegrass. When Monroe's new sound began spreading in the late 1940s, Canadian country music could boast several home-grown successes such as Hank Snow and Wilf Carter, but many young musicians became hooked on bluegrass's collective spirit. Bill Monroe's vision stemmed directly from the social plight of the Great Depression, where the notion of teamwork was crucial. Although he was the leader, there were no readily apparent "stars" in the Blue Grass Boys. Each musician had his fair opportunity to shine at the microphone, and was expected to rise to the occasion. Monroe ran the band like a manager would run a baseball team, and bluegrass's appeal was rooted in the fanciful idea that each song provided a chance for any musician to knock one out of the park.

Neil Rosenberg is one of the leading bluegrass historians in North America, and a recently retired professor of folklore studies at Memorial University in St. John's, Newfoundland. He points to a small, but passionate contingent of Canadian country music fans who picked up on the music right from the start. "Lots of people heard Bill Monroe on the radio because he was on the Grand Ole Opry, and that was broadcast over WSM in Nashville, which could be heard in Canada," Rosenberg says. "He was making records for Columbia, which made them widely available."

Among the first Canadian bluegrass bands, according to Rosenberg, were the York County Boys from Toronto, who released their first album in 1958 on the Arc label, and appeared at the first Mariposa Folk Festival in 1961. A folk revival was in full swing; bluegrass was just one aspect. Although many regions of Canada featured cultural similarities to the Appalachian roots of bluegrass, Rosenberg points out that these may be more complicated than they appear. "The migration of people from the Maritimes to find work in Ontario was very similar to the migration of people from Appalachia to big American cities," he says. "They both brought their music with them and introduced it to a new setting. Obviously, Irish music has always been a big part of life in the Maritimes and Newfoundland. And with the fiddle being such an important aspect of bluegrass, people might assume that these two styles are closely related. But bluegrass as a form was different enough that musicians who grew up playing Irish music and wanted to play bluegrass really had to relearn a lot of what they knew. That process didn't really take hold until the 1970s in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, where there was a long-standing country music tradition dating back generations. Here in Newfoundland, where people still grow up with Irish music, the bluegrass scene is still developing."

Rosenberg's own band, Crooked Stovepipe, which also includes former York County Boys' mandolin player Rex Yetman, has played a big role in developing the East coast bluegrass community. But in the '70s, rock fans across Canada acquired a taste for bluegrass through the dabblings of bands like the Grateful Dead and the Clarence White-era Byrds. (White's family actually had Acadian roots in New Brunswick, changing their name from LeBlanc when they migrated over the border to Maine. His brother Roland continues the family tradition of playing bluegrass.) The '70s also saw the emergence of the "new grass" movement, spurred on by artists like Emmylou Harris and Ricky Skaggs.

In the 1980s in Toronto, a roots music scene blossomed on Queen Street that turned the clock back to the 1950s. Handsome Ned's faithful take on rockabilly and country paved the way for bands like Blue Rodeo and Cowboy Junkies. By the mid-'90s, the place to hear bluegrass in Toronto was the Silver Dollar, where Heartbreak Hill held court on a weekly basis. Comprised of Jenny Whiteley on bass and vocals, her brother Dan on mandolin, Dottie Cormier on guitar and vocals, and Chris Quinn on banjo, their musical prowess in a predominantly traditional style turned hipsters onto bluegrass, and helped reintroduce it to the folk festival circuit. Unfortunately, they would only make one album, the 1998 self-titled release that earned a Juno nomination, before splitting for solo careers.

Heartbreak Hill's legacy has been taken up by the Backstabbers, fronted by "Colonel" Tom Parker and Bob Hannon. Their weekly Sunday afternoon sets at the Cameron House became mandatory for all roots fans, and their dedication to the "old time" aesthetic became their trademark. "We would play every night if we could," Parker says. "Playing bluegrass is so demanding that you really have to play as much as possible just to keep your chops up."

The Backstabbers recorded their first album, Country Stringband, in the old time way, live around a single microphone; the bulk of the material consisted of original songs by Parker and Hannon. Although they steadfastly stuck to a classic look and sound, Parker says it was always important to write their own material, rather than relying on the bluegrass songbook.

That attitude hasn't always been appreciated by the bluegrass establishment; in fact, the scene has been notorious for its conservatism, a result of Bill Monroe's unwavering opinions on how to play the music he created. Throughout his career, Monroe earned a mean-spirited reputation by frequently chastising musicians for not playing by his rules and having the audacity to call their music bluegrass. Partly for that reason, Parker doesn't call the Backstabbers a bluegrass band - their line-up doesn't include a banjo.

Straddling the line between rural and urban, traditional and innovative, the Backstabbers more often play rock clubs than festivals and Legion Halls. "To be able to play all the time we really have to approach what we do the same way that rock bands do," according to Parker. "Each album we've put out has done better than the last, so it seems like we're reaching people who have never listened to bluegrass much before."

The other way to reach people who have never heard bluegrass before is to ignore the rules completely and adopt a contemporary sound. Over the past half-decade, Vancouver duo Jesse Zubot and Steve Dawson have done precisely that. When they first teamed up in the mid-'90s, Zubot & Dawson were a hit on the festival circuit, mixing elements of jazz and world music with traditional tunes, in sync with the West coast "hippie" vibe. Their touchstones were groundbreaking virtuosos like Bela Fleck, Bill Frisell and Kelly Joe Phelps, and they adopted a similar mandate to explore new directions within their chosen instruments' limitations.

"I didn't listen to a lot of old music growing up," Dawson says. "I actually went to school with Gillian Welch and David Rawlings and got familiar with some of it through what they were starting to do, but it wasn't until I met Jesse that I really took to it. He came from a family that had him playing it his whole life. I was playing mostly electric guitar in rock bands. "I didn't come to understand what bluegrass was really about until we started playing festivals and crossed paths with Heartbreak Hill. What impressed me most was how dedicated they were to playing their instruments. We would stay up all night just jamming. It seemed like those guys had an endless capacity to play, and it really made me rethink my approach to what I was doing."

That textured, instrumental-heavy approach turned out to be something so different that Zubot & Dawson saved critics the trouble of trying to categorise it by coining the term "strang," the title of their debut album. By their second album, Tractor Parts: Further Adventures In Strang, the pair were adding loops and sampling to Zubot's fiddle and mandolin and Dawson's dobro. While open-eared listeners were immediately responsive, Dawson admits that they have run into their fair share of doubters.

"It certainly hasn't been easy playing the kind of music we do," he says. "We've gone through many booking agents and played lots of gigs where we haven't provided what the audience was probably expecting. We're not a conventional band by any stretch, so it's always been a challenge to find places to play."

Dawson has done his part to foster the West coast scene by helping to establish the label Black Hen Music, as well as produce other artists, including Jenny Whiteley's two Juno-winning solo albums. This summer he'll release his first solo album, We Belong To The Gold Coast, but Dawson says with some reluctance that the acoustic music scene in B.C. is not as thriving as some might think.

"I guess there is a 'West coast sound,' if you include all the players from here down to California. It's really where the whole 'new grass' thing started with David Grisman and Bela Fleck and folks like that. But around here the scene is pretty small."

Dawson's insinuation that bluegrass-based music is not tailored for just anyone to play may be true, but that isn't preventing new groups from taking up the challenge. Jon Bartlett has worked in many styles, but since forming his roots-based outfit Greenfield Main, this pillar of the Ottawa scene has been incorporating bluegrass elements more and more. The band's latest album, Barnburners & Heartchurners, is their most musically accomplished yet, although Bartlett is hesitant to admit it.

"I would never dare to call what we do bluegrass, just because we're not that good as musicians," he says. "I'm more of a fan of old time music and just relate to its simplicity and honesty. I think anyone who takes a lo-fi approach to music and recording can feel at least some connection to that stuff because in the same way, it wasn't about the technology, but the performance."

The echoes of bluegrass are certainly evident in Bartlett's current incarnation, but it's his experience in the indie rock world that is the biggest influence on the direction of the band. Unlike the Backstabbers, he feels much more trepidation in trying to play acoustic music in rock clubs, believing that some rock elements need to be in place in order to hold an audience's attention.

"There is a hardcore bluegrass scene that exists in the smaller towns in the Ottawa Valley, and we've ventured into it a couple of times without much success," he says. "People there just didn't seem to accept what we were doing. generally we're more comfortable playing a club with a band like the Sadies or the Fiftymen - we share the same old time influences, but it's a rock show."

Whether it becomes more common on the rock club circuit, or remains the domain of folk festivals, bluegrass will likely remain an underground music in Canada. It doesn't have to remain regional though, according to Neil Rosenberg. "I think that lovers of bluegrass in Canada understand that it is part of our culture to a certain degree and it should be accepted just as other forms of folk music have been accepted in the culture. But I suppose as long as the artists are so spread out, no one is really going to get to know each other, and people are going to miss out on a lot of great music."

No Second Fiddles: The Current Crop Of Canadian Bluegrass

The Bills

Formerly the Bill Hilly Band, in their new incarnation there is a greater emphasis on instrumental experimentation, and even classical influences.

Clover Point Drifters

Fairly new outfit made up of bluegrass veterans from Victoria, B.C. They have a laid-back west coast approach, and a sense of humour. Only album is self-released Grapes On The Vine.

Crazy Strings

Former Heartbreak Hill members continue the weekly bluegrass jam at Toronto's Silver Dollar every Wednesday. Always an uplifting experience.

Creaking Tree String Quartet

Predominantly instrumental group rooted in bluegrass, but also mixes elements of jazz and classical arrangements. Self-titled debut was nominated for a 2004 Juno.

Crooked Stovepipe

Newfoundland's finest bluegrass band, featuring the vast experience of Neil Rosenberg and Rex Yetman. Currently finishing a new album, and building the bluegrass scene on the Rock.

The Foggy Hogtown Boys

Another unit comprised of many of Toronto's established bluegrass pickers, they are faithful to a classic sound and work diligently to promote it to new audiences. Expect a new album in the fall.

The Grascals

Although Nashville-based, their line-up includes Ontario-born banjo player David Talbot who has also become an in-demand session star. Latest album includes cover of "Viva Las Vegas" that's actually getting radio play.

House Of Doc

Transplanted west coast family band, they rely on four-part harmonies and mix Celtic and blues into their unorthodox approach. Brand new album, Prairiegrass, produced by Spirit Of The West's Vince Ditrich.

The Jaybirds

B.C. unit formed by California mandolin player John Reischman, they are mostly known only on the west coast, even venturing to Alaska for their annual Bluegrass Cruise. Latest album is The Road West.

But listen more closely; it's apparent that this isn't just a representation of a mythical America that no one in the room can honestly say they have experienced - local Toronto locales get name-dropped regularly in the Backstabbers' original tunes. "I think it always comes back to bluegrass being a reflection of the community," mandolinist "Colonel" Tom Parker says. "We're not going to write songs about working in coal mines. We're living in Toronto, so we're going to write about what's going on around us. But the emotions behind the songs never change, and that's what will always keep people interested in bluegrass."

It's a dilemma that is not uncommon to most genres of music: purists versus progressives. But bluegrass, with its uniquely regional image (the rural South), and the fact that it is the invention of one man (Bill Monroe), has been faced with this conflict since Monroe and his Blue Grass Boys put out their first record.

In Canada, bluegrass has existed on an even shakier foundation. Although many parts of the country share similar cultural roots, it's perceived as a purely American form. While that has hindered Canada in developing a national bluegrass community, a new batch of young musicians - be they Vancouver's Zubot and Dawson, Winnipeg's the Duhks or Ottawa's Greenfield Main - are adding their own personal stamp. Interpretations from this new generation have meant not playing by the rules, which during Monroe's lifetime, was heresy.

"Bluegrass," according to Monroe's stringently held guidelines, is strictly defined by its instrumentation: mandolin, banjo, fiddle, guitar, upright bass and group harmonies. Like Henry Ford upgrading from four-cylinders to V8's, in the 1940s, Monroe and his Blue Grass Boys took "old time" string band music and added a driving rhythmic kick that relied heavily on the virtuosity of his musicians, most notably banjo player Earl Scruggs, whose blinding technique redefined the instrument. It was also music that stayed true to the values of family, religion, and hard work. Like a jazz bandleader, Monroe pushed his players' talents to their physical limit; in terms of energy and group interaction, he foreshadowed rock'n'roll. (It's no coincidence that the flip side of Elvis Presley's first single was his version of Monroe's "Blue Moon of Kentucky.")

Since Monroe's time (his career continued until his death in 1996), bluegrass and other "old time" acoustic music enjoyed a thriving, if unheralded, place in the lives of music lovers. But it was only the shocking success of the O Brother Where Art Thou? soundtrack that swung the spotlight toward it. Breakthroughs like that are impossible to predict, but an emphasis on innovation usually provides the best chance to reach wider audiences.

This year's biggest breakthrough belongs to Winnipeg's the Duhks, who, after landing a deal for their self-titled debut album on the venerable American roots label Sugar Hill, are spending the rest of the year touring everywhere except their homeland. Formed in 2002 by banjo player Len Podolak, whose parents were among the original organisers of the Winnipeg Folk Festival, the Duhks represent a youthful naivety toward old time music, not relying so much on virtuosity, but on throwing any influence they can into the mix and topping it off with a punky attitude.

"Our main intention when we started was to get people to dance," Podolak says. "All this music that we love and that's part of our sound - bluegrass, Irish music, French-Canadian music, Afro-Cuban music - it's all really distinct, but it's all related. A lot of the instrumentation is similar, like the fiddle, so what people are responding to is hearing all of these different influences, but we're not forcing it. We're just playing our instruments the way we know how."

On The Duhks, the band tackles everything from the folk standard "The Wagoner's Lad," to Leonard Cohen's "Everybody Knows." Growing up within the folk festival environment is what Podolak credits for erasing any barriers he had when it came to playing music. "My original intention was to play an updated version of old time music, but once we got the line-up solidified, we became this collective, sharing so many different styles. I got to see so many amazing performers at the festival when I was a kid that it's never really crossed my mind to limit myself to a certain sound. The banjo isn't a traditional Irish instrument, but that's never stopped me from playing those melodies."

Podolak's open-mindedness seems in keeping with Canada's general attitude toward bluegrass. When Monroe's new sound began spreading in the late 1940s, Canadian country music could boast several home-grown successes such as Hank Snow and Wilf Carter, but many young musicians became hooked on bluegrass's collective spirit. Bill Monroe's vision stemmed directly from the social plight of the Great Depression, where the notion of teamwork was crucial. Although he was the leader, there were no readily apparent "stars" in the Blue Grass Boys. Each musician had his fair opportunity to shine at the microphone, and was expected to rise to the occasion. Monroe ran the band like a manager would run a baseball team, and bluegrass's appeal was rooted in the fanciful idea that each song provided a chance for any musician to knock one out of the park.

Neil Rosenberg is one of the leading bluegrass historians in North America, and a recently retired professor of folklore studies at Memorial University in St. John's, Newfoundland. He points to a small, but passionate contingent of Canadian country music fans who picked up on the music right from the start. "Lots of people heard Bill Monroe on the radio because he was on the Grand Ole Opry, and that was broadcast over WSM in Nashville, which could be heard in Canada," Rosenberg says. "He was making records for Columbia, which made them widely available."

Among the first Canadian bluegrass bands, according to Rosenberg, were the York County Boys from Toronto, who released their first album in 1958 on the Arc label, and appeared at the first Mariposa Folk Festival in 1961. A folk revival was in full swing; bluegrass was just one aspect. Although many regions of Canada featured cultural similarities to the Appalachian roots of bluegrass, Rosenberg points out that these may be more complicated than they appear. "The migration of people from the Maritimes to find work in Ontario was very similar to the migration of people from Appalachia to big American cities," he says. "They both brought their music with them and introduced it to a new setting. Obviously, Irish music has always been a big part of life in the Maritimes and Newfoundland. And with the fiddle being such an important aspect of bluegrass, people might assume that these two styles are closely related. But bluegrass as a form was different enough that musicians who grew up playing Irish music and wanted to play bluegrass really had to relearn a lot of what they knew. That process didn't really take hold until the 1970s in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, where there was a long-standing country music tradition dating back generations. Here in Newfoundland, where people still grow up with Irish music, the bluegrass scene is still developing."

Rosenberg's own band, Crooked Stovepipe, which also includes former York County Boys' mandolin player Rex Yetman, has played a big role in developing the East coast bluegrass community. But in the '70s, rock fans across Canada acquired a taste for bluegrass through the dabblings of bands like the Grateful Dead and the Clarence White-era Byrds. (White's family actually had Acadian roots in New Brunswick, changing their name from LeBlanc when they migrated over the border to Maine. His brother Roland continues the family tradition of playing bluegrass.) The '70s also saw the emergence of the "new grass" movement, spurred on by artists like Emmylou Harris and Ricky Skaggs.

In the 1980s in Toronto, a roots music scene blossomed on Queen Street that turned the clock back to the 1950s. Handsome Ned's faithful take on rockabilly and country paved the way for bands like Blue Rodeo and Cowboy Junkies. By the mid-'90s, the place to hear bluegrass in Toronto was the Silver Dollar, where Heartbreak Hill held court on a weekly basis. Comprised of Jenny Whiteley on bass and vocals, her brother Dan on mandolin, Dottie Cormier on guitar and vocals, and Chris Quinn on banjo, their musical prowess in a predominantly traditional style turned hipsters onto bluegrass, and helped reintroduce it to the folk festival circuit. Unfortunately, they would only make one album, the 1998 self-titled release that earned a Juno nomination, before splitting for solo careers.

Heartbreak Hill's legacy has been taken up by the Backstabbers, fronted by "Colonel" Tom Parker and Bob Hannon. Their weekly Sunday afternoon sets at the Cameron House became mandatory for all roots fans, and their dedication to the "old time" aesthetic became their trademark. "We would play every night if we could," Parker says. "Playing bluegrass is so demanding that you really have to play as much as possible just to keep your chops up."

The Backstabbers recorded their first album, Country Stringband, in the old time way, live around a single microphone; the bulk of the material consisted of original songs by Parker and Hannon. Although they steadfastly stuck to a classic look and sound, Parker says it was always important to write their own material, rather than relying on the bluegrass songbook.

That attitude hasn't always been appreciated by the bluegrass establishment; in fact, the scene has been notorious for its conservatism, a result of Bill Monroe's unwavering opinions on how to play the music he created. Throughout his career, Monroe earned a mean-spirited reputation by frequently chastising musicians for not playing by his rules and having the audacity to call their music bluegrass. Partly for that reason, Parker doesn't call the Backstabbers a bluegrass band - their line-up doesn't include a banjo.

Straddling the line between rural and urban, traditional and innovative, the Backstabbers more often play rock clubs than festivals and Legion Halls. "To be able to play all the time we really have to approach what we do the same way that rock bands do," according to Parker. "Each album we've put out has done better than the last, so it seems like we're reaching people who have never listened to bluegrass much before."

The other way to reach people who have never heard bluegrass before is to ignore the rules completely and adopt a contemporary sound. Over the past half-decade, Vancouver duo Jesse Zubot and Steve Dawson have done precisely that. When they first teamed up in the mid-'90s, Zubot & Dawson were a hit on the festival circuit, mixing elements of jazz and world music with traditional tunes, in sync with the West coast "hippie" vibe. Their touchstones were groundbreaking virtuosos like Bela Fleck, Bill Frisell and Kelly Joe Phelps, and they adopted a similar mandate to explore new directions within their chosen instruments' limitations.

"I didn't listen to a lot of old music growing up," Dawson says. "I actually went to school with Gillian Welch and David Rawlings and got familiar with some of it through what they were starting to do, but it wasn't until I met Jesse that I really took to it. He came from a family that had him playing it his whole life. I was playing mostly electric guitar in rock bands. "I didn't come to understand what bluegrass was really about until we started playing festivals and crossed paths with Heartbreak Hill. What impressed me most was how dedicated they were to playing their instruments. We would stay up all night just jamming. It seemed like those guys had an endless capacity to play, and it really made me rethink my approach to what I was doing."

That textured, instrumental-heavy approach turned out to be something so different that Zubot & Dawson saved critics the trouble of trying to categorise it by coining the term "strang," the title of their debut album. By their second album, Tractor Parts: Further Adventures In Strang, the pair were adding loops and sampling to Zubot's fiddle and mandolin and Dawson's dobro. While open-eared listeners were immediately responsive, Dawson admits that they have run into their fair share of doubters.

"It certainly hasn't been easy playing the kind of music we do," he says. "We've gone through many booking agents and played lots of gigs where we haven't provided what the audience was probably expecting. We're not a conventional band by any stretch, so it's always been a challenge to find places to play."

Dawson has done his part to foster the West coast scene by helping to establish the label Black Hen Music, as well as produce other artists, including Jenny Whiteley's two Juno-winning solo albums. This summer he'll release his first solo album, We Belong To The Gold Coast, but Dawson says with some reluctance that the acoustic music scene in B.C. is not as thriving as some might think.

"I guess there is a 'West coast sound,' if you include all the players from here down to California. It's really where the whole 'new grass' thing started with David Grisman and Bela Fleck and folks like that. But around here the scene is pretty small."

Dawson's insinuation that bluegrass-based music is not tailored for just anyone to play may be true, but that isn't preventing new groups from taking up the challenge. Jon Bartlett has worked in many styles, but since forming his roots-based outfit Greenfield Main, this pillar of the Ottawa scene has been incorporating bluegrass elements more and more. The band's latest album, Barnburners & Heartchurners, is their most musically accomplished yet, although Bartlett is hesitant to admit it.

"I would never dare to call what we do bluegrass, just because we're not that good as musicians," he says. "I'm more of a fan of old time music and just relate to its simplicity and honesty. I think anyone who takes a lo-fi approach to music and recording can feel at least some connection to that stuff because in the same way, it wasn't about the technology, but the performance."

The echoes of bluegrass are certainly evident in Bartlett's current incarnation, but it's his experience in the indie rock world that is the biggest influence on the direction of the band. Unlike the Backstabbers, he feels much more trepidation in trying to play acoustic music in rock clubs, believing that some rock elements need to be in place in order to hold an audience's attention.

"There is a hardcore bluegrass scene that exists in the smaller towns in the Ottawa Valley, and we've ventured into it a couple of times without much success," he says. "People there just didn't seem to accept what we were doing. generally we're more comfortable playing a club with a band like the Sadies or the Fiftymen - we share the same old time influences, but it's a rock show."

Whether it becomes more common on the rock club circuit, or remains the domain of folk festivals, bluegrass will likely remain an underground music in Canada. It doesn't have to remain regional though, according to Neil Rosenberg. "I think that lovers of bluegrass in Canada understand that it is part of our culture to a certain degree and it should be accepted just as other forms of folk music have been accepted in the culture. But I suppose as long as the artists are so spread out, no one is really going to get to know each other, and people are going to miss out on a lot of great music."

No Second Fiddles: The Current Crop Of Canadian Bluegrass

The Bills

Formerly the Bill Hilly Band, in their new incarnation there is a greater emphasis on instrumental experimentation, and even classical influences.

Clover Point Drifters

Fairly new outfit made up of bluegrass veterans from Victoria, B.C. They have a laid-back west coast approach, and a sense of humour. Only album is self-released Grapes On The Vine.

Crazy Strings

Former Heartbreak Hill members continue the weekly bluegrass jam at Toronto's Silver Dollar every Wednesday. Always an uplifting experience.

Creaking Tree String Quartet

Predominantly instrumental group rooted in bluegrass, but also mixes elements of jazz and classical arrangements. Self-titled debut was nominated for a 2004 Juno.

Crooked Stovepipe

Newfoundland's finest bluegrass band, featuring the vast experience of Neil Rosenberg and Rex Yetman. Currently finishing a new album, and building the bluegrass scene on the Rock.

The Foggy Hogtown Boys

Another unit comprised of many of Toronto's established bluegrass pickers, they are faithful to a classic sound and work diligently to promote it to new audiences. Expect a new album in the fall.

The Grascals

Although Nashville-based, their line-up includes Ontario-born banjo player David Talbot who has also become an in-demand session star. Latest album includes cover of "Viva Las Vegas" that's actually getting radio play.

House Of Doc

Transplanted west coast family band, they rely on four-part harmonies and mix Celtic and blues into their unorthodox approach. Brand new album, Prairiegrass, produced by Spirit Of The West's Vince Ditrich.

The Jaybirds

B.C. unit formed by California mandolin player John Reischman, they are mostly known only on the west coast, even venturing to Alaska for their annual Bluegrass Cruise. Latest album is The Road West.