Even if youve never read a single page of Bill Willinghams brilliant comic series Fables, you already know all the players if not exactly in this form. Starting with the foundation of Hans Christian Andersen, the Brothers Grimm and the fables of Aesop, Willingham has created a remarkable world full of damsels, princesses, cads and morphing creatures. But beyond Little Red Riding Hood and Snow White, Willingham has expanded the world of Fables to include most any tale passed down to generations of children.

The scope had an appropriately innocent genesis. "I wanted Snow White [then an administrator in their Fabletown community] to have some sort of clerk/assistant basically to be in the room for her character to talk to, he explains. "So I came up with Little Boy Blue from the nursery rhyme. I put him in there as kind of a throwaway his job is just to be there. [I didnt want] to use up one of the important fairy tale characters for what would be an unimportant slot. That opened it up so, I guess Fables also includes characters from nursery rhymes. Now, Willingham says, "the ultimate definition is simply a character Im interested in and thats in the public domain [of copyright].

Not wanting to wade willy-nilly into peoples beloved childhood memories, Willingham imposed certain restrictions, ones that have actually paid off brilliantly, in storytelling terms. "One of the rules I set for myself is that whatever the original story or nursery rhyme or song ballad they came from has to have been true. Snow White did stay with seven dwarfs and get rescued by the dashing prince. Those things had to have occurred, but then I feel fairly free in asking What could have occurred to this character? Thats how we have Goldilocks of the Three Bears fame grow up to be a pretty radical Marx-spouting revolutionary.

Another twist in Willinghams vision is the brilliant merging of similar characters from different tales; it stemmed from an early confusion regarding a certain lupine villain. "Ever since childhood, I was certain that the Big Bad Wolf from Red Riding Hood was the same Big Bad Wolf from the Three Little Pigs. Once I decided that, it got instantly habit-forming [in Fables]. Of course Prince Charming is the same prince who married Snow White and Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty. If he was married and divorced so many times, he must be a bit of a rake and a womanizer. The delight of Fables aside from Willinghams brilliant storytelling chops and the dramatic heft hes given to even the most throwaway one off characters (like the aforementioned Boy Blue, whose journey has spun into much more than being an audience for Snow White) is in the seemingly endless potential of its premise. With built-in back-stories, its not hard to extrapolate the tension that might exist between, say, Charming and Bigby (as the wolf is known here).

Not everyone saw such immediate potential when the series was pitched almost a decade ago. "I was doing a lot of limited series work for DC and [Fables publisher] Vertigo at the time Sandman spin-offs and some other things. Some of them were selling in the high dozens, but they got some critical attention. When I pitched Fables, I was pretty humble at the time. [Yet] measured against that humility was the kind of arrogance that anyone has trying to get into this business I was pretty confident that this was a good idea, because I pitched it as an ongoing series. DC was interested, but to quote one of the editors, I dont think we can get more than one story out of it, so maybe we could just do a six-issue mini-series. That kind of flabbergasted me; I couldnt see how someone couldnt see all the potential from this concept. I was buoyed by the fact that [then DC publisher] Jeanette Khan was really behind [it] and thought she could get a movie out of it.

Fables has journeyed into the Hollywood machine more than once: as a feature film and TV pilot, live action and animated. "Ive discovered that the machine resembles nothing so much as a meat grinder, Willingham says of the experience. "But heres the big secret Hollywood exists entirely on soilent green produced by people who feed their poor blasted souls into it. Thank god if [a film or TV adaptation] ever does happen, its someone elses lookout and not mine. It would be nice, but I dont expect anything from it. The real Fables would still be the comic book as far as Im concerned.

Jack of All Trades

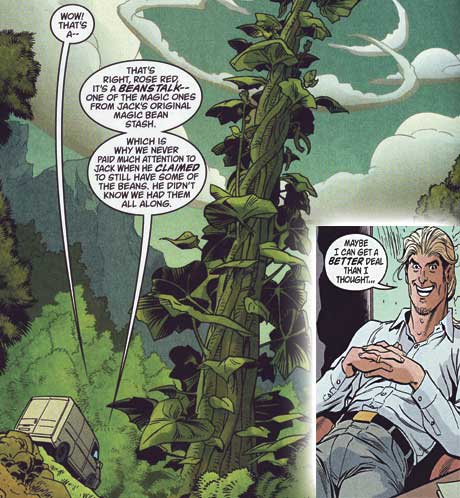

The biggest beneficiary of Willinghams vision of merging similar fairytale characters is Jack. "There are tons of Jack characters in fairytales and folklore, he says. "In each case Jack Frost, Little Jack Horner, Jack Sprat, Jack and the Beanstalk "he was a bit of a snot and a trickster character. Though he made appearances in early Fables stories, Jack of Fables has been spun off into his own book, with a distinctly different tone.

"We established that Fables even though it got pretty silly at times was basically a series story. Jack, even when he was a member of the Fables cast, was always a chaotic element thrown into that mess. He just cries out to get silly and absurd. Spinning him off into his own series which we definitely wanted to have its own character, and not just be Fables Jr. or Fables Lite quickly became about what kind of ridiculous situations we can get the character into. The tenor of Jack is to search for that next moment of shock or great joke, while Fables is the search for that next great dramatic or poignant moment. The way I look at it now is that Fables is the sober, 9 to 5, this is your job work, and writing Jack is that wild drunken weekend to blow off steam before you have to get back to serious work again on Monday.

The scope had an appropriately innocent genesis. "I wanted Snow White [then an administrator in their Fabletown community] to have some sort of clerk/assistant basically to be in the room for her character to talk to, he explains. "So I came up with Little Boy Blue from the nursery rhyme. I put him in there as kind of a throwaway his job is just to be there. [I didnt want] to use up one of the important fairy tale characters for what would be an unimportant slot. That opened it up so, I guess Fables also includes characters from nursery rhymes. Now, Willingham says, "the ultimate definition is simply a character Im interested in and thats in the public domain [of copyright].

Not wanting to wade willy-nilly into peoples beloved childhood memories, Willingham imposed certain restrictions, ones that have actually paid off brilliantly, in storytelling terms. "One of the rules I set for myself is that whatever the original story or nursery rhyme or song ballad they came from has to have been true. Snow White did stay with seven dwarfs and get rescued by the dashing prince. Those things had to have occurred, but then I feel fairly free in asking What could have occurred to this character? Thats how we have Goldilocks of the Three Bears fame grow up to be a pretty radical Marx-spouting revolutionary.

Another twist in Willinghams vision is the brilliant merging of similar characters from different tales; it stemmed from an early confusion regarding a certain lupine villain. "Ever since childhood, I was certain that the Big Bad Wolf from Red Riding Hood was the same Big Bad Wolf from the Three Little Pigs. Once I decided that, it got instantly habit-forming [in Fables]. Of course Prince Charming is the same prince who married Snow White and Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty. If he was married and divorced so many times, he must be a bit of a rake and a womanizer. The delight of Fables aside from Willinghams brilliant storytelling chops and the dramatic heft hes given to even the most throwaway one off characters (like the aforementioned Boy Blue, whose journey has spun into much more than being an audience for Snow White) is in the seemingly endless potential of its premise. With built-in back-stories, its not hard to extrapolate the tension that might exist between, say, Charming and Bigby (as the wolf is known here).

Not everyone saw such immediate potential when the series was pitched almost a decade ago. "I was doing a lot of limited series work for DC and [Fables publisher] Vertigo at the time Sandman spin-offs and some other things. Some of them were selling in the high dozens, but they got some critical attention. When I pitched Fables, I was pretty humble at the time. [Yet] measured against that humility was the kind of arrogance that anyone has trying to get into this business I was pretty confident that this was a good idea, because I pitched it as an ongoing series. DC was interested, but to quote one of the editors, I dont think we can get more than one story out of it, so maybe we could just do a six-issue mini-series. That kind of flabbergasted me; I couldnt see how someone couldnt see all the potential from this concept. I was buoyed by the fact that [then DC publisher] Jeanette Khan was really behind [it] and thought she could get a movie out of it.

Fables has journeyed into the Hollywood machine more than once: as a feature film and TV pilot, live action and animated. "Ive discovered that the machine resembles nothing so much as a meat grinder, Willingham says of the experience. "But heres the big secret Hollywood exists entirely on soilent green produced by people who feed their poor blasted souls into it. Thank god if [a film or TV adaptation] ever does happen, its someone elses lookout and not mine. It would be nice, but I dont expect anything from it. The real Fables would still be the comic book as far as Im concerned.

Jack of All Trades

The biggest beneficiary of Willinghams vision of merging similar fairytale characters is Jack. "There are tons of Jack characters in fairytales and folklore, he says. "In each case Jack Frost, Little Jack Horner, Jack Sprat, Jack and the Beanstalk "he was a bit of a snot and a trickster character. Though he made appearances in early Fables stories, Jack of Fables has been spun off into his own book, with a distinctly different tone.

"We established that Fables even though it got pretty silly at times was basically a series story. Jack, even when he was a member of the Fables cast, was always a chaotic element thrown into that mess. He just cries out to get silly and absurd. Spinning him off into his own series which we definitely wanted to have its own character, and not just be Fables Jr. or Fables Lite quickly became about what kind of ridiculous situations we can get the character into. The tenor of Jack is to search for that next moment of shock or great joke, while Fables is the search for that next great dramatic or poignant moment. The way I look at it now is that Fables is the sober, 9 to 5, this is your job work, and writing Jack is that wild drunken weekend to blow off steam before you have to get back to serious work again on Monday.