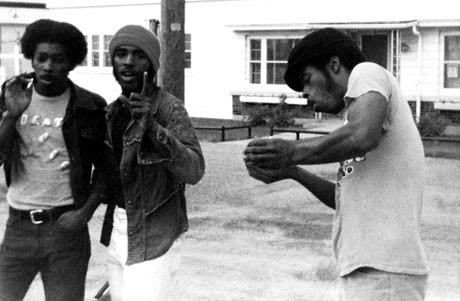

Forgotten even by the men who made it, ...For the Whole World to See is part of a debut album that never was by three brothers from Detroit during the mid-'70s. Fighting against stereotypes and embracing their city's influence, they made some of the fiercest and inspiring rock'n'roll ever uncovered, thankfully by the fans at Drag City. Originally touted and then rejected by bigwig record exec Clive Davis because they wouldn't change their name, Death fed their music the piss'n'vinegar that founded punk the same year this was recorded. They matched the intensity of hometown heroes the MC5, pulled out riffage and hooks that outdid Thin Lizzy and set the stage for obvious disciples like Bad Brains. With only seven tracks, ...For isn't a complete statement by any means - more material is set for a later release - but it opens your ears to one of the era's great lost albums and biggest oversights with anthems, jams and freak outs that touched on both the freedom of music ("Rock-N-Roll Victim") and the oppression of the system ("Politicians In My Eyes"). This is powerful, riff-ravaged rock'n'roll that deserves to be worshipped the second time around.

How did Death become a rock'n'roll band?

Vocalist/bassist: Bobby Hackney: We were doing what typical bands were doing at the time, backing up soul singing groups, and went into this metamorphosis from funk into rock, which really exploded on us. We had such a great wealth of bands playing the scene, like Ted Nugent, Iggy and the Stooges, Grand Funk Railroad, Wayne Kramer and the MC5. We really got into the power trio thing. During that time you wasn't tuned into life if you wasn't tuned into what Hendrix and the Beatles were doing. So if you took all that and put it on top, that was our influence. And then there was the black community with Motown and rhythm and blues.

You're often cited as a proto-punk band. Did it feel like you were on to something different at the time?

My brother David had a strong, strong conviction that we were doing something different. We did a limited edition single and David used to have two turntables set up and he would play rock records and compare the two. He'd demonstrate how our music was so different; we used to call it "hard drivin'." We weren't trying to predate anything, we didn't even know what punk was at the time. We were just trying to be a good rock'n'roll band.

Do you think the colour of your skin made a difference?

I think it made us edgier. We were in the black community and at the time people would tell us what we should be playing, like the black music of the day, and that just made us edgier. Like Spinal Tap, my brother David would cut it up to 11 out of pure defiance for the people who were constantly on his case. We were going through so much rejection for being too loud, too fast, too crazy, too wild. But this was the black community. There was other people in the outskirts of Michigan who just loved us.

And you guys got involved with Clive Davis?

Well we would have! [Laughs] Don Davis was the man who first signed us up; he owned a company called Groovesville Productions, one of the primary recording studios in Detroit - the same studio that Berry Gordy cut records for Jackie Wilson, John Lee Hooker recorded there. It was called the United Sounds Studio back then. Don bought it and changed the name to Groovesville, and signed some significant acts like the Dramatics. He was doing pretty good at the time with Marilyn McCoo and Billy Davis, he had established a good relationship with Clive; he was always taking him tapes to check out. And Clive had heard a tape of ours and liked what he heard, but didn't like the name of our band. We had a whole concept behind the band, and my brother David was pretty sure we would get another deal elsewhere. So he told Don Davis that we wouldn't change our name, and Clive wasn't interested, and that soured things with Don. We realized that he wasn't shopping us so hard.

Did you get much of a reaction over your name back then, other than Clive Davis?

Oh sure! People were shocked by it. Even our family members tried to convince us to change our name. Clive wasn't the only one. By the time it got to him we had heard that so much, we had become really rigid towards anyone telling us to change our name. We were just being rock'n'rollers man, we were standing up to the system and we just wasn't backing down. We had our concept and that was it.

So, did the name kill the band then?

No, no, no. It didn't define us at all. After our deal with Groovesville soured we found ourselves in a lull between the end of '76 and the beginning of '77, and we came to Vermont with the concept of Death. But being in a new area, we were very good musicians and people liked the music but were scared of the name, so we changed it to the Fourth Movement. We recorded two more albums and a single. My brother kinda got homesick of Detroit, and we kinda changed to a Christian concept, but it was a struggle, even though we recordd some awesome music. So David went back to Detroit and me and my brother Dannis stayed here in Vermont. Being a great college town, we continued our education, and through our association with the University of Vermont, we worked during the day and went to school at night. I became a disc jockey and got involved with a whole bunch of local music entrepreneurs, one of which was a promoter who brought Bob Marley to town. We got influenced by reggae music, because here we were a bassist and a drummer, and the bass and drum of reggae appealed to a bassist and drummer. It was frustrating finding a guitar player, especially one of David's calibre, and we had just given up hope. So we just went into this bass and drum thing and that's when we became Lambsbread. And that's the gist of it.

How did the rebirth of Death happen?

We had been through so much rejection in the days of Death, that we just vaulted everything away. But we always kept it in our heart, like it was a family heirloom. Recently, my son in California called me and said "Dad, did you realize that they're playing your music here at underground parties?" And then my older son went online and found that a single had been circulating with collectors for years, and we didn't even know! My brother and I had not heard the music in years, we hadn't gotten the reel-to-reel out to sit down and reminisce.

Is ...For the Whole World to See everything there is?

Not everything. There are some other songs and demos. Not much, but there is still some garage-style stuff that Death did in the '70s that we're in touch with Drag City about to possibly release it in the future.

How did you get in touch with Drag City?

My son knew a gentleman named Ben Blackwell who got a record in Detroit of ours. And his uncle is involved with another record label, and it was this whole connection. It's just been wild.

How does it feel to see the album finally get released?

It's weird! You create something, you go through the battleground of it, and it takes years and years, I'm just glad that I'm around to see it. Unfortunately, our brother David isn't around. It just takes so long sometimes for people to appreciate something. We are definitely in awe about it. It's hard for us to comprehend still, even though we've been in the thick of it for the last four or five months.

Your sons' band Rough Francis are now touring playing the songs of Death?

They've really captured the spirit. It's really interesting to see them pick it up so quickly. My kids have been playing hardcore for a while now, and after listening to the Death stuff they know it's in their blood! They found their missing link.

(Drag City)How did Death become a rock'n'roll band?

Vocalist/bassist: Bobby Hackney: We were doing what typical bands were doing at the time, backing up soul singing groups, and went into this metamorphosis from funk into rock, which really exploded on us. We had such a great wealth of bands playing the scene, like Ted Nugent, Iggy and the Stooges, Grand Funk Railroad, Wayne Kramer and the MC5. We really got into the power trio thing. During that time you wasn't tuned into life if you wasn't tuned into what Hendrix and the Beatles were doing. So if you took all that and put it on top, that was our influence. And then there was the black community with Motown and rhythm and blues.

You're often cited as a proto-punk band. Did it feel like you were on to something different at the time?

My brother David had a strong, strong conviction that we were doing something different. We did a limited edition single and David used to have two turntables set up and he would play rock records and compare the two. He'd demonstrate how our music was so different; we used to call it "hard drivin'." We weren't trying to predate anything, we didn't even know what punk was at the time. We were just trying to be a good rock'n'roll band.

Do you think the colour of your skin made a difference?

I think it made us edgier. We were in the black community and at the time people would tell us what we should be playing, like the black music of the day, and that just made us edgier. Like Spinal Tap, my brother David would cut it up to 11 out of pure defiance for the people who were constantly on his case. We were going through so much rejection for being too loud, too fast, too crazy, too wild. But this was the black community. There was other people in the outskirts of Michigan who just loved us.

And you guys got involved with Clive Davis?

Well we would have! [Laughs] Don Davis was the man who first signed us up; he owned a company called Groovesville Productions, one of the primary recording studios in Detroit - the same studio that Berry Gordy cut records for Jackie Wilson, John Lee Hooker recorded there. It was called the United Sounds Studio back then. Don bought it and changed the name to Groovesville, and signed some significant acts like the Dramatics. He was doing pretty good at the time with Marilyn McCoo and Billy Davis, he had established a good relationship with Clive; he was always taking him tapes to check out. And Clive had heard a tape of ours and liked what he heard, but didn't like the name of our band. We had a whole concept behind the band, and my brother David was pretty sure we would get another deal elsewhere. So he told Don Davis that we wouldn't change our name, and Clive wasn't interested, and that soured things with Don. We realized that he wasn't shopping us so hard.

Did you get much of a reaction over your name back then, other than Clive Davis?

Oh sure! People were shocked by it. Even our family members tried to convince us to change our name. Clive wasn't the only one. By the time it got to him we had heard that so much, we had become really rigid towards anyone telling us to change our name. We were just being rock'n'rollers man, we were standing up to the system and we just wasn't backing down. We had our concept and that was it.

So, did the name kill the band then?

No, no, no. It didn't define us at all. After our deal with Groovesville soured we found ourselves in a lull between the end of '76 and the beginning of '77, and we came to Vermont with the concept of Death. But being in a new area, we were very good musicians and people liked the music but were scared of the name, so we changed it to the Fourth Movement. We recorded two more albums and a single. My brother kinda got homesick of Detroit, and we kinda changed to a Christian concept, but it was a struggle, even though we recordd some awesome music. So David went back to Detroit and me and my brother Dannis stayed here in Vermont. Being a great college town, we continued our education, and through our association with the University of Vermont, we worked during the day and went to school at night. I became a disc jockey and got involved with a whole bunch of local music entrepreneurs, one of which was a promoter who brought Bob Marley to town. We got influenced by reggae music, because here we were a bassist and a drummer, and the bass and drum of reggae appealed to a bassist and drummer. It was frustrating finding a guitar player, especially one of David's calibre, and we had just given up hope. So we just went into this bass and drum thing and that's when we became Lambsbread. And that's the gist of it.

How did the rebirth of Death happen?

We had been through so much rejection in the days of Death, that we just vaulted everything away. But we always kept it in our heart, like it was a family heirloom. Recently, my son in California called me and said "Dad, did you realize that they're playing your music here at underground parties?" And then my older son went online and found that a single had been circulating with collectors for years, and we didn't even know! My brother and I had not heard the music in years, we hadn't gotten the reel-to-reel out to sit down and reminisce.

Is ...For the Whole World to See everything there is?

Not everything. There are some other songs and demos. Not much, but there is still some garage-style stuff that Death did in the '70s that we're in touch with Drag City about to possibly release it in the future.

How did you get in touch with Drag City?

My son knew a gentleman named Ben Blackwell who got a record in Detroit of ours. And his uncle is involved with another record label, and it was this whole connection. It's just been wild.

How does it feel to see the album finally get released?

It's weird! You create something, you go through the battleground of it, and it takes years and years, I'm just glad that I'm around to see it. Unfortunately, our brother David isn't around. It just takes so long sometimes for people to appreciate something. We are definitely in awe about it. It's hard for us to comprehend still, even though we've been in the thick of it for the last four or five months.

Your sons' band Rough Francis are now touring playing the songs of Death?

They've really captured the spirit. It's really interesting to see them pick it up so quickly. My kids have been playing hardcore for a while now, and after listening to the Death stuff they know it's in their blood! They found their missing link.