Reading through an issue of Ottawa cartoonist Dave Cooper's Weasel feels like walking through a greenhouse. A steamy nimbus of creative energy clings to stories like "Ripple: A Predilection for Tina," in which Martin, an artist approaching middle age, grows increasingly obsessed with his homely, possibly teen-aged figure model. "I actually wrote the story probably two years before starting to draw it," explains Cooper. "I just couldn't bring myself to work on it, because I knew I wasn't good enough for it. I was drawing too literally it would have ended up like a mainstream comic book or something: realistic people and clean lines."

Cooper's effort to draw a "more honest and thoughtful" story paid off after he attended a series of life-drawing sessions. "For some reason it just really worked for me. In school, I never really grasped drawing the nude form. But when I took these workshops, it was like I was mentally ready for it." The ripe, heated style he has since developed serves "Ripple" well: zigzag hatching scurries around the edges of figures and faces, or swarms lovingly over Tina's rotund body, releasing a hum of sexual longing with which Martin's solitude easily resonates. "With the first issue of Weasel, I was even aware myself that I'd improved. I still have affection for my earlier stuff, but I don't think it's anywhere near as good as Weasel."

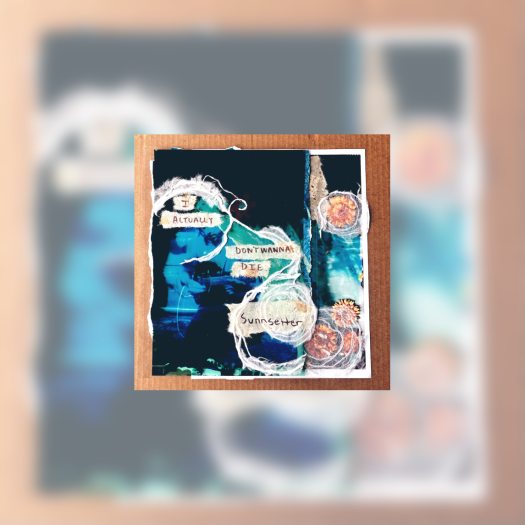

Fantagraphics released the first issue of Weasel in 1999; in 2000, Cooper won the Harvey Award for Best New Series. Weasel reads a lot like Clowes' early issues of Eightball it's a real browser's delight. Like Clowes, Cooper treats his book as a showcase for his fecund talent. But instead of Clowes' wry awareness of generic conventions, Cooper offers a raunchy, slightly menacing vibe. "Ripple" commands the most prominent place in Weasel, but Cooper rounds out each issue with a loot bag-full of subsidiary treats as well: a cartoon called "television series x-32b" (drawn in the style Cooper uses for his long-running "Pip & Norton" strip in Vice magazine), one-shot strips, cutaway drawings of creepy appliances, renderings of remembered dreams, and reproductions of Cooper's oil paintings.

Weasel's diverse content also reflects Cooper's busy professional life. "I'm always pretty overworked with commercial illustration or design or animation," he says. A series of posters for Nortel "basically paid my rent for the next year." Another of his posters will promote the Ottawa Student Animation Festival, for which Cooper will also be making the festival's signal film. "At the beginning of every screening at the festival, they have this one or two minute short the only thing it has to do is show the logo for the festival; it's like an identification kind of thing. But it's become this excuse to make a really crazy little film."

The festival film won't be Cooper's first work in animation. He has produced several short films, including one for Cartoon Network.com. His career in animation started with an auspicious meeting: a few years ago, fellow Fantagraphics artist Bob Fingerman introduced him to Matt Groening in San Diego. Cooper gave Groening a copy of his 1996 Harvey-nominated book Suckle, and several months later, Groening appeared at one of Cooper's signings. "It was kind of mysterious. He said, We have this new project that we're working on that I can't say the name of, but expect a call from my producer, because we want you to work on it.'" Cooper was soon churning out "drawings of robots and spaceships and cityscapes and stuff" for what would become Futurama. "It was basically about three or four months of just drawing, just doodling and having fun. Near the end, it got more specific, where they were trying to nail a particular vehicle. That spaceship that they drive around in? I think I did about 12 completely different versions of that ship. And they ended up using somebody else's design anyway."

Cooper's effort to draw a "more honest and thoughtful" story paid off after he attended a series of life-drawing sessions. "For some reason it just really worked for me. In school, I never really grasped drawing the nude form. But when I took these workshops, it was like I was mentally ready for it." The ripe, heated style he has since developed serves "Ripple" well: zigzag hatching scurries around the edges of figures and faces, or swarms lovingly over Tina's rotund body, releasing a hum of sexual longing with which Martin's solitude easily resonates. "With the first issue of Weasel, I was even aware myself that I'd improved. I still have affection for my earlier stuff, but I don't think it's anywhere near as good as Weasel."

Fantagraphics released the first issue of Weasel in 1999; in 2000, Cooper won the Harvey Award for Best New Series. Weasel reads a lot like Clowes' early issues of Eightball it's a real browser's delight. Like Clowes, Cooper treats his book as a showcase for his fecund talent. But instead of Clowes' wry awareness of generic conventions, Cooper offers a raunchy, slightly menacing vibe. "Ripple" commands the most prominent place in Weasel, but Cooper rounds out each issue with a loot bag-full of subsidiary treats as well: a cartoon called "television series x-32b" (drawn in the style Cooper uses for his long-running "Pip & Norton" strip in Vice magazine), one-shot strips, cutaway drawings of creepy appliances, renderings of remembered dreams, and reproductions of Cooper's oil paintings.

Weasel's diverse content also reflects Cooper's busy professional life. "I'm always pretty overworked with commercial illustration or design or animation," he says. A series of posters for Nortel "basically paid my rent for the next year." Another of his posters will promote the Ottawa Student Animation Festival, for which Cooper will also be making the festival's signal film. "At the beginning of every screening at the festival, they have this one or two minute short the only thing it has to do is show the logo for the festival; it's like an identification kind of thing. But it's become this excuse to make a really crazy little film."

The festival film won't be Cooper's first work in animation. He has produced several short films, including one for Cartoon Network.com. His career in animation started with an auspicious meeting: a few years ago, fellow Fantagraphics artist Bob Fingerman introduced him to Matt Groening in San Diego. Cooper gave Groening a copy of his 1996 Harvey-nominated book Suckle, and several months later, Groening appeared at one of Cooper's signings. "It was kind of mysterious. He said, We have this new project that we're working on that I can't say the name of, but expect a call from my producer, because we want you to work on it.'" Cooper was soon churning out "drawings of robots and spaceships and cityscapes and stuff" for what would become Futurama. "It was basically about three or four months of just drawing, just doodling and having fun. Near the end, it got more specific, where they were trying to nail a particular vehicle. That spaceship that they drive around in? I think I did about 12 completely different versions of that ship. And they ended up using somebody else's design anyway."