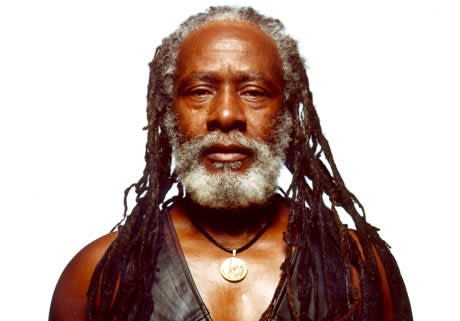

Some voices carry an air of authority. People like Johnny Cash, Mahlathini, Curtis Mayfield and Prince Far I have righteous charisma that never fades into the background. Winston Rodney, aka Burning Spear, is one such vocalist. For the past 35 years, his nasal, chant-like vocals have sounded like a country preacher, and his lyrics have always suited his declamatory style. His faraway sound is an echo of Jamaica's past, when home grown harmonies redefined notions of sharp and flat, before this funkiness was smoothed away by the influence of decades of American R&B. Despite Winston Rodney's pastoral vibes, he is very hands-on about his career, putting into practice the economic self-determination forwarded by his hero, Marcus Garvey. He has maintained his distance from the urban pressure cooker that is Kingston, Jamaica never writing "Concrete Jungle style protests about the ghetto experience, never over-recorded by a bevy of producers, never striving for success in the dancehalls and, from early on, employing hand-picked musicians and seeking control over his own recordings. He has set and pursued his own agenda, never deviating from the messages he came forth with from the beginning, and as such, his story is a major part of the history of roots reggae. 2003's Free Man marks his first wholly independent, internationally distributed studio CD. From his roots in St. Ann's Bay (also Garveys birthplace), to touring around the world as much as ten months a year, Rodney has global experience to inform his universal perspective on Rastafari.

1969 to 1974

Winston Rodney is born March 1, 1945 (some accounts maintain 1948) in St. Ann's Bay on the north coast of Jamaica. He grows up with eight brothers and four sisters. Unusually, he has no musical inclinations until shortly before his first recording activity. Speaking to him now, Rodney says only that "It took some time for the music to come out. It was only 1969 when it was ready. His entry into music is precipitated by an encounter with Bob Marley also a native of the parish of St. Ann in the countryside near Marleys farm. After asking Marley about how to break into the music business in Jamaica, Marley suggests Rodney go to Studio One, easily the dominant recording studio and record label of the time. In Kingston, Rodney auditions for label head Coxsone Dodd with the song "Door Peep." The house musicians almost laugh the country boy out of the audition; only bassist Leroy Sibbles takes a liking to his sound. Taking the name "Burning Spear from Kenyan president Jomo Kenyattas nickname, this nom de plume becomes synonymous with Rodneys own.

Rodney's time at Jamaicas "musical college shows that his artistic vision is remarkably well developed. His clarion call vocals, accompanied by partner Rupert Willington, seem to float over the chugging Studio One rhythms. This music, somewhere between languid and propulsive, was a key tributary of what would become roots reggae. Lyrically, his work at Studio One represents some of the earliest examples of Rasta reasoning on record, since Rastafarians are still very much social pariahs in Jamaica at this time. While the music made during this period is enduring, it resulted in only one hit: 1972's "Joe Frazier (He Prayed)." Nevertheless, two full-length albums result from his work in this period: 1973s Studio One Presents Burning Spear and 1974s Rocking Time. By the end of 1974, Rodney is fed up with the lack of payment and control over his music, which would be a recurring theme with record companies throughout his career.

1975 to 1976

Rodney retires to St. Anns Bay to contemplate his next move. He is approached by local sound system operator Jack Ruby, who offers a 50/50 partnership. The first single the pair produces, "Marcus Garvey," provides a new template for Burning Spear, now a trio with the addition of Delroy Hinds (brother of ska vocalist Justin Hinds). The partnership between Ruby and Spear produces one of the all-time great reggae records, Marcus Garvey. Whereas the Studio One sound is increasingly stuck in the past, Marcus Garvey is the sound of the present, blending the early 70s Wailers sound (best captured on Burnin and Talking Blues) with plaintive horns, chanted lyrics and jazz-tinged guitar work from veteran session player Earl "Chinna" Smith. Always intended as an album-length statement, each song iterates different aspects of Garveyism and Rasta teaching. The title tune single-handedly revives interest in Garvey's life and teachings, which had been overshadowed by the more radical black leaders of the 60s.

Ruby, in an interview with Carl Gayle in the liner notes of 2001 Spear Records compilation Spear Burning, recounts: "The first evening Burning Spear album come out, two thousand album come in [the office] and I couldnt get a copy to carry home. People line up; two thousand record come without jacket and I, the producer, couldnt get a copy.

Internationally, the album is released on Island. As had been done with Marley's Island releases, the mix of the album is lightened, lessening the bass and speeding up tracks. Rodneys take on this, from Spear Burnings liner notes, is less furious than philosophical: "Island never notify the artists but try to adjust and fit in with the vibes that were going on at the time. Changed up everything. Better they left the album the way it was created. Many fans castigate Island to this day for messing with this masterpiece and subsequent recordings. Rodney starts Spear Records as an outlet for his own productions without the interference of other parties; the label would last until 1979. Despite his lack of hands-on studio experience or musical training, Spear is able to achieve his own sound without Jack Rubys production expertise.

In 1976, the first of his many dub albums is released. Garveys Ghost (again remixed by Island) isnt so much a dub album as an instrumental version of Marcus Garvey. The official follow-up to Garvey, Man In the Hills, is the mirror image of Marcus Garvey: a description of rural Rastafari living as opposed to a study of global social concerns. Hills is also dedicated to reinterpretations of the Studio One tracks in a manner more befitting his current musical style increasingly four-to-the-floor rockers grooves and spacy mixes featuring horn charts straight from Mt. Zion.

1977 to 1979

The end of the 1970s sees the unravelling of all Spears professional relationships. In 1977, Spear ceases working with Ruby, Willington and Hines. Dry and Heavy marks his last album with his original backing band, the Black Disciples. Seldom has a title been so evocative of the music within; this is another classic, distinguished by the comparative sparseness of the vocals and even more dub-wise production. 1978s Marcus' Children pushes the dub factor to its fullest extent on any Spear recording. By now, Island is beginning to withdraw its support since it appears that the success of Marcus Garvey is not likely to be repeated. Spear's mystic, laid-back music, while conscious and articulate, is not provocative in a superstar-creating manner as that of Bob Marley and Peter Tosh. Marcus Children is not released domestically in the U.S. (In 1994, this album would be lovingly remastered by then-nascent reissue label Blood and Fire under the name Social Living; now out of print, it is mastered from the original tapes, as opposed to the re-eqed Island mix that is currently available.) A dub version, entitled Living Dub, originally mixed by veteran engineer Sylvan Morris, appears for a brief period in 1979. This is the last original album Island releases of Rodneys material in the 70s, although five compilations have chronicled this chapter in Rodneys career.

Despite Island's withdrawal of support, his releases become hugely popular in Britain and are especially inspirational to the UKs Rasta communities. A tour exposes him to the punk boom across the UK, which proves receptive to Rastafaris idealism. Burning Spear Live is recorded featuring Aswad, then Britains premier reggae band; the sense of excitement from the band, the audience and Spear are palpable and make for a great live album.

In 1979, Spear makes a featured appearance in the movie Rockers. The movie is kind of The Harder They Come for the late 70s Kingston music scene, with much more Rasta content. Spear provides one of the most memorable moments in the film as he sings "Jah No Dead while sitting on a rocky outcrop by the sea, accompanied only by the surf crashing around him. Spear appears at the inaugural Reggae Sunsplash, with whom he would appear and tour overseas for years to come, planting the foundation of his international reputation.

1980 to 1985

Now recording on his own, Rodneys next move takes him to Marleys Tuff Gong studio to team up with the Wailers (minus drummer Carlton Barrett) on yet another classic album: Hail H.I.M. The result is a sound contemporaneous with Marleys Uprising album of the same year, but with tougher grooves and drummer Nelson Miller providing a more driving "rockers foundation than is associated with the Wailers. This album is the least dub-wise Spear album yet, as if Living Dub had cleaved the dub from Spears music. Perhaps to compensate, Living Dub Volume 2, again mixed by Sylvan Morris, is briefly released this same year. One could argue that Spears sound has not changed much since this time, with allowances for changing keyboard sounds and recording techniques. Hail H.I.M. is licensed to EMI in 1980; it is released in the UK and Europe, but not in the States. Major label interest in reggae wanes following the 1981 death of Bob Marley: Virgins Frontline closes, while Island and to a lesser extent EMI scale back reggae involvement, which would open the door to independent labels.

Farover, something of a tribute album to Marley, is again recorded independently and proves to be a turning point in Spears career its his first album to gain U.S. release since Dry and Heavy. Recorded for EMI Europe, its picked up for distribution by indie Heartbeat Records. In 1982, Heartbeat (an offshoot of folk label Rounder Records) makes Farover one of its first releases, giving the label a much-needed jumpstart in the large, still untapped American reggae market. With the release of the Fittest of the Fittest in 1983 and more appearances at Sunsplash and in Europe, Spear is on the rise again. His final album of this period, 1984s Resistance, is another strong effort, garnering Spears first Grammy nomination.

1986 to 1990

In a curious move, Burning Spear signs with L.A. punk label Slash, which has no other reggae artists. The three albums he releases on Slash feature various attempts to diversify his sound; clearly hes trying to cross over. California also has the most receptive reggae market in the U.S., a factor that (along with Slashs Warner distribution deal) may have contributed to the decision. But artistically, this period is Rodneys low ebb. People of the World is released with great fanfare and garners another Grammy nomination, but now sounds seriously dated. Both 1988s Mistress Music and his second live album Live in Paris, Zenith 88 are the weakest of his career, if not in message then certainly in terms of their slick production style and big synths. Yet these albums are among Spears best-distributed and promoted albums to date. Many U.S. fans rave nostalgically about these albums as their first introduction to Spear. Rodney himself has kind words for Slash now. "They were good people. They let me buy my albums back at a reasonable price. EMI were not so good.

1990 to 1992

Spear's two latter-day albums for Island, Mek We Dweet and Jah Kingdom move into a different crossover sound. The rock factor is toned down and the electronics are deployed more sensibly, though many dismiss these albums as reggae-lite due to their generally upbeat moods. The former garners yet another Grammy nomination while the inclusion of a tough, hip-hop flavoured dub of "Great Men," on Island's influential Rebirth of the Cool series, finds him yet another new segment of fans. These albums also mark a new direction in Spear's songcraft: this was a sound of a Rastaman fitting into a larger context, reasoning with different people than he would have had he remained in Jamaica. A fitting example is his seemingly unlikely cover of "Estimated Prophet" on the Grateful Dead tribute album Deadicated. His treatment of a song filled with supernatural imagery gave it new depth Rodney has mused that he wished he had written the song. Despite breaking new ground, Spears second go with Island comes to a quick end. Spear leaves Jamaica for good (although he returns many times a year and continues to record there) to take up residence in Queens, NY.

1993 to 1996

Sensibly, Spear returns to Heartbeat, now the leading American chronicler of reggae. A flurry of releases and investment in Spear's career results. Both volumes of Living Dub are reissued, newly re-dubbed by engineer Barry OHare, though they do not surpass the magic of Sylvan Morriss original mixes. Love and Peace is another live album, giving the tracks from Jah Kingdom and Mek We Dweet more room to breathe. This is followed by two studio albums, The World Should Know and Rasta Business, in 1993 and 1995, and a collaboration with fellow roots artist Fred Locks on his 12 The Hard Way. Rasta Business gets a huge push, including three videos (unheard of in the reggae community), and garners another Grammy nom. Living Dub Volume 3 is a tame dub version of Rasta Business. The grooves on each successive Heartbeat release bear a stronger resemblance to 70s production values, sounding better and better each time out. As roots reggae starts to make a comeback, Spear remains in great voice, touring obsessively and never playing for less than two hours. In 1996, Island releases the best compilation yet of his work, entitled Chant Down Babylon. While Marcus Garvey has never gone out of print, other crucial material finally gets its due and the best distribution it has ever received.

1997 to 2001

Entrenched as an elder statesman, and with a strong resurgence in rootical content in Jamaica, Spear gets more and more deserved recognition. The folk-tinged Appointment With His Majesty is another strong album; a Grammy nomination follows. The companion album Living Dub Volume 4, like Volume 3, was something of an afterthought. But his best album of the last ten years is undoubtedly 1999s Calling Rastafari, which finally wins him a Grammy after eight tries. Lyrically, he's sharper than he has been for some time, sounding road wizened and applying the personal convictions of his faith to examples throughout the world. The Burning Bands deep grooves combined with the fuller mix make it a modern classic that easily ranks near the top of anything he'd done since 1980. All at the ripe old age of 54.

2002 to 2004

Three years after Calling Rastafari, a fourth live album (Live in Montreux) is released on the Burning Music label, marking his first independent release since the demise of the Spear label more than 20 years earlier. It would prove another turning point when Spear records his new studio album, Free Man. "Heartbeat had the first option to release Free Man but they turned it down, he explains. "I have recorded and financed much on my own, so I felt I could to it all with Burning Music Productions. Free Mans tunes are mostly good-time easy listening reggae with allusions to his independent status, not trusting those who claim to be trustworthy, and as always, following the teachings of Rastafari, Marcus Garvey and respecting the old school of reggae. Nearly 60, Burning Spear still has gas in the tank but could be nearing the end of his vigorous touring career. Hes still preaching the same message, but in his case its a mark of consistency a preacher doesn't suddenly come up with new and different ways to preach just for the sake of novelty. Plus, Spear finally has all business elements under his control: recording, production, distribution, promotion and legal representation. There are many manifestations of Rastafari, and, as Garvey said, self-reliance is the key.

1969 to 1974

Winston Rodney is born March 1, 1945 (some accounts maintain 1948) in St. Ann's Bay on the north coast of Jamaica. He grows up with eight brothers and four sisters. Unusually, he has no musical inclinations until shortly before his first recording activity. Speaking to him now, Rodney says only that "It took some time for the music to come out. It was only 1969 when it was ready. His entry into music is precipitated by an encounter with Bob Marley also a native of the parish of St. Ann in the countryside near Marleys farm. After asking Marley about how to break into the music business in Jamaica, Marley suggests Rodney go to Studio One, easily the dominant recording studio and record label of the time. In Kingston, Rodney auditions for label head Coxsone Dodd with the song "Door Peep." The house musicians almost laugh the country boy out of the audition; only bassist Leroy Sibbles takes a liking to his sound. Taking the name "Burning Spear from Kenyan president Jomo Kenyattas nickname, this nom de plume becomes synonymous with Rodneys own.

Rodney's time at Jamaicas "musical college shows that his artistic vision is remarkably well developed. His clarion call vocals, accompanied by partner Rupert Willington, seem to float over the chugging Studio One rhythms. This music, somewhere between languid and propulsive, was a key tributary of what would become roots reggae. Lyrically, his work at Studio One represents some of the earliest examples of Rasta reasoning on record, since Rastafarians are still very much social pariahs in Jamaica at this time. While the music made during this period is enduring, it resulted in only one hit: 1972's "Joe Frazier (He Prayed)." Nevertheless, two full-length albums result from his work in this period: 1973s Studio One Presents Burning Spear and 1974s Rocking Time. By the end of 1974, Rodney is fed up with the lack of payment and control over his music, which would be a recurring theme with record companies throughout his career.

1975 to 1976

Rodney retires to St. Anns Bay to contemplate his next move. He is approached by local sound system operator Jack Ruby, who offers a 50/50 partnership. The first single the pair produces, "Marcus Garvey," provides a new template for Burning Spear, now a trio with the addition of Delroy Hinds (brother of ska vocalist Justin Hinds). The partnership between Ruby and Spear produces one of the all-time great reggae records, Marcus Garvey. Whereas the Studio One sound is increasingly stuck in the past, Marcus Garvey is the sound of the present, blending the early 70s Wailers sound (best captured on Burnin and Talking Blues) with plaintive horns, chanted lyrics and jazz-tinged guitar work from veteran session player Earl "Chinna" Smith. Always intended as an album-length statement, each song iterates different aspects of Garveyism and Rasta teaching. The title tune single-handedly revives interest in Garvey's life and teachings, which had been overshadowed by the more radical black leaders of the 60s.

Ruby, in an interview with Carl Gayle in the liner notes of 2001 Spear Records compilation Spear Burning, recounts: "The first evening Burning Spear album come out, two thousand album come in [the office] and I couldnt get a copy to carry home. People line up; two thousand record come without jacket and I, the producer, couldnt get a copy.

Internationally, the album is released on Island. As had been done with Marley's Island releases, the mix of the album is lightened, lessening the bass and speeding up tracks. Rodneys take on this, from Spear Burnings liner notes, is less furious than philosophical: "Island never notify the artists but try to adjust and fit in with the vibes that were going on at the time. Changed up everything. Better they left the album the way it was created. Many fans castigate Island to this day for messing with this masterpiece and subsequent recordings. Rodney starts Spear Records as an outlet for his own productions without the interference of other parties; the label would last until 1979. Despite his lack of hands-on studio experience or musical training, Spear is able to achieve his own sound without Jack Rubys production expertise.

In 1976, the first of his many dub albums is released. Garveys Ghost (again remixed by Island) isnt so much a dub album as an instrumental version of Marcus Garvey. The official follow-up to Garvey, Man In the Hills, is the mirror image of Marcus Garvey: a description of rural Rastafari living as opposed to a study of global social concerns. Hills is also dedicated to reinterpretations of the Studio One tracks in a manner more befitting his current musical style increasingly four-to-the-floor rockers grooves and spacy mixes featuring horn charts straight from Mt. Zion.

1977 to 1979

The end of the 1970s sees the unravelling of all Spears professional relationships. In 1977, Spear ceases working with Ruby, Willington and Hines. Dry and Heavy marks his last album with his original backing band, the Black Disciples. Seldom has a title been so evocative of the music within; this is another classic, distinguished by the comparative sparseness of the vocals and even more dub-wise production. 1978s Marcus' Children pushes the dub factor to its fullest extent on any Spear recording. By now, Island is beginning to withdraw its support since it appears that the success of Marcus Garvey is not likely to be repeated. Spear's mystic, laid-back music, while conscious and articulate, is not provocative in a superstar-creating manner as that of Bob Marley and Peter Tosh. Marcus Children is not released domestically in the U.S. (In 1994, this album would be lovingly remastered by then-nascent reissue label Blood and Fire under the name Social Living; now out of print, it is mastered from the original tapes, as opposed to the re-eqed Island mix that is currently available.) A dub version, entitled Living Dub, originally mixed by veteran engineer Sylvan Morris, appears for a brief period in 1979. This is the last original album Island releases of Rodneys material in the 70s, although five compilations have chronicled this chapter in Rodneys career.

Despite Island's withdrawal of support, his releases become hugely popular in Britain and are especially inspirational to the UKs Rasta communities. A tour exposes him to the punk boom across the UK, which proves receptive to Rastafaris idealism. Burning Spear Live is recorded featuring Aswad, then Britains premier reggae band; the sense of excitement from the band, the audience and Spear are palpable and make for a great live album.

In 1979, Spear makes a featured appearance in the movie Rockers. The movie is kind of The Harder They Come for the late 70s Kingston music scene, with much more Rasta content. Spear provides one of the most memorable moments in the film as he sings "Jah No Dead while sitting on a rocky outcrop by the sea, accompanied only by the surf crashing around him. Spear appears at the inaugural Reggae Sunsplash, with whom he would appear and tour overseas for years to come, planting the foundation of his international reputation.

1980 to 1985

Now recording on his own, Rodneys next move takes him to Marleys Tuff Gong studio to team up with the Wailers (minus drummer Carlton Barrett) on yet another classic album: Hail H.I.M. The result is a sound contemporaneous with Marleys Uprising album of the same year, but with tougher grooves and drummer Nelson Miller providing a more driving "rockers foundation than is associated with the Wailers. This album is the least dub-wise Spear album yet, as if Living Dub had cleaved the dub from Spears music. Perhaps to compensate, Living Dub Volume 2, again mixed by Sylvan Morris, is briefly released this same year. One could argue that Spears sound has not changed much since this time, with allowances for changing keyboard sounds and recording techniques. Hail H.I.M. is licensed to EMI in 1980; it is released in the UK and Europe, but not in the States. Major label interest in reggae wanes following the 1981 death of Bob Marley: Virgins Frontline closes, while Island and to a lesser extent EMI scale back reggae involvement, which would open the door to independent labels.

Farover, something of a tribute album to Marley, is again recorded independently and proves to be a turning point in Spears career its his first album to gain U.S. release since Dry and Heavy. Recorded for EMI Europe, its picked up for distribution by indie Heartbeat Records. In 1982, Heartbeat (an offshoot of folk label Rounder Records) makes Farover one of its first releases, giving the label a much-needed jumpstart in the large, still untapped American reggae market. With the release of the Fittest of the Fittest in 1983 and more appearances at Sunsplash and in Europe, Spear is on the rise again. His final album of this period, 1984s Resistance, is another strong effort, garnering Spears first Grammy nomination.

1986 to 1990

In a curious move, Burning Spear signs with L.A. punk label Slash, which has no other reggae artists. The three albums he releases on Slash feature various attempts to diversify his sound; clearly hes trying to cross over. California also has the most receptive reggae market in the U.S., a factor that (along with Slashs Warner distribution deal) may have contributed to the decision. But artistically, this period is Rodneys low ebb. People of the World is released with great fanfare and garners another Grammy nomination, but now sounds seriously dated. Both 1988s Mistress Music and his second live album Live in Paris, Zenith 88 are the weakest of his career, if not in message then certainly in terms of their slick production style and big synths. Yet these albums are among Spears best-distributed and promoted albums to date. Many U.S. fans rave nostalgically about these albums as their first introduction to Spear. Rodney himself has kind words for Slash now. "They were good people. They let me buy my albums back at a reasonable price. EMI were not so good.

1990 to 1992

Spear's two latter-day albums for Island, Mek We Dweet and Jah Kingdom move into a different crossover sound. The rock factor is toned down and the electronics are deployed more sensibly, though many dismiss these albums as reggae-lite due to their generally upbeat moods. The former garners yet another Grammy nomination while the inclusion of a tough, hip-hop flavoured dub of "Great Men," on Island's influential Rebirth of the Cool series, finds him yet another new segment of fans. These albums also mark a new direction in Spear's songcraft: this was a sound of a Rastaman fitting into a larger context, reasoning with different people than he would have had he remained in Jamaica. A fitting example is his seemingly unlikely cover of "Estimated Prophet" on the Grateful Dead tribute album Deadicated. His treatment of a song filled with supernatural imagery gave it new depth Rodney has mused that he wished he had written the song. Despite breaking new ground, Spears second go with Island comes to a quick end. Spear leaves Jamaica for good (although he returns many times a year and continues to record there) to take up residence in Queens, NY.

1993 to 1996

Sensibly, Spear returns to Heartbeat, now the leading American chronicler of reggae. A flurry of releases and investment in Spear's career results. Both volumes of Living Dub are reissued, newly re-dubbed by engineer Barry OHare, though they do not surpass the magic of Sylvan Morriss original mixes. Love and Peace is another live album, giving the tracks from Jah Kingdom and Mek We Dweet more room to breathe. This is followed by two studio albums, The World Should Know and Rasta Business, in 1993 and 1995, and a collaboration with fellow roots artist Fred Locks on his 12 The Hard Way. Rasta Business gets a huge push, including three videos (unheard of in the reggae community), and garners another Grammy nom. Living Dub Volume 3 is a tame dub version of Rasta Business. The grooves on each successive Heartbeat release bear a stronger resemblance to 70s production values, sounding better and better each time out. As roots reggae starts to make a comeback, Spear remains in great voice, touring obsessively and never playing for less than two hours. In 1996, Island releases the best compilation yet of his work, entitled Chant Down Babylon. While Marcus Garvey has never gone out of print, other crucial material finally gets its due and the best distribution it has ever received.

1997 to 2001

Entrenched as an elder statesman, and with a strong resurgence in rootical content in Jamaica, Spear gets more and more deserved recognition. The folk-tinged Appointment With His Majesty is another strong album; a Grammy nomination follows. The companion album Living Dub Volume 4, like Volume 3, was something of an afterthought. But his best album of the last ten years is undoubtedly 1999s Calling Rastafari, which finally wins him a Grammy after eight tries. Lyrically, he's sharper than he has been for some time, sounding road wizened and applying the personal convictions of his faith to examples throughout the world. The Burning Bands deep grooves combined with the fuller mix make it a modern classic that easily ranks near the top of anything he'd done since 1980. All at the ripe old age of 54.

2002 to 2004

Three years after Calling Rastafari, a fourth live album (Live in Montreux) is released on the Burning Music label, marking his first independent release since the demise of the Spear label more than 20 years earlier. It would prove another turning point when Spear records his new studio album, Free Man. "Heartbeat had the first option to release Free Man but they turned it down, he explains. "I have recorded and financed much on my own, so I felt I could to it all with Burning Music Productions. Free Mans tunes are mostly good-time easy listening reggae with allusions to his independent status, not trusting those who claim to be trustworthy, and as always, following the teachings of Rastafari, Marcus Garvey and respecting the old school of reggae. Nearly 60, Burning Spear still has gas in the tank but could be nearing the end of his vigorous touring career. Hes still preaching the same message, but in his case its a mark of consistency a preacher doesn't suddenly come up with new and different ways to preach just for the sake of novelty. Plus, Spear finally has all business elements under his control: recording, production, distribution, promotion and legal representation. There are many manifestations of Rastafari, and, as Garvey said, self-reliance is the key.