Buffy Sainte-Marie is a re-doer. Or, to put it in environmentally appropriate terms, a recycler and a reuser.

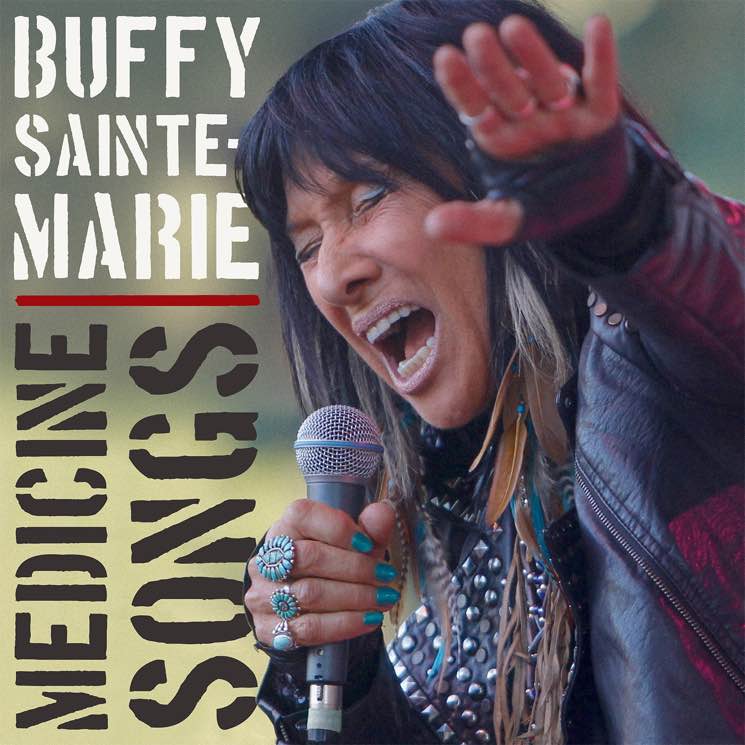

Over the course of 50-odd years, her songs have sustained relevancy so that if you place songs she wrote in the '60s alongside songs from the '90s, early 2000s and ones from today, they will resonate and sound powerfully of this moment. That's what Buffy does in concert, and also what she does here on her 19th album, Medicine Songs, which brings together songs that uplift as much as educate about the plight of Indigenous people and push back against the greedy, warmongering, environmentally destructive powers that be. And sometimes, as Buffy says, you can dance to it.

It's like a Buffy Sainte-Marie retrospective, only the older songs are re-recorded using her current instrumental preferences and selected for thematic relevance. Unlike her Polaris Prize-winning 2015 record Power in the Blood, there are no love songs; Medicine Songs is unflinching in its focus.

Sainte-Marie kicks Medicine Songs off in high gear with "You Got to Run (Spirit of the Wind)," a universal and uplifting stadium-ready collaboration with fellow Polaris Prize-winner Tanya Tagaq. She then moves on to "The War Racket," a bass-y, synth-laden staple of her current live set and a takedown of war-supporting billionaires and politicians.

From there, Medicine Songs moves into borrowing: from older Buffy albums, from the traditional songbook (patriotic 1910 song "America the Beautiful" features two new Sainte-Marie-written verses here) and, surprisingly, from the still quite recent Power in the Blood ("Carry It On," "Power in the Blood" and, in the downloadable bonus tracks, "Generation" join this group, sounding as though they've been unaltered from her last album's takes).

Sainte-Marie worked with Chris Birkett, one of the three producers on Power in the Blood, this time around, and for the most part they've managed to carry Sainte-Marie's older songs sonically into the present using her current equipment. Brushed-up versions of powwow vocal-laden "Starwalker" (from 1976's Up Where We Belong), "Little Wheel Spin and Spin" and "Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee" sound extra vital.

Interestingly, Sainte-Marie revisits a number of songs from 1992's Coincidence and Likely Stories — five, if you take into consideration the bonus material. Perhaps she thought that people may have missed that collection the first time around, and wanted to give these songs another opportunity. "You say silver burns a hole in your pocket and gold burns a hole in your soul / Well, uranium burns a hole in forever / It just gets out of control," she talk-sings on almost the almost spoken-word "The Priests of the Golden Bull."

Sainte-Marie can be a total rocker, but the most poignant moment on the album is arguably her raw public address-like folk song, "My Country 'Tis of Thy People You're Dying." Like "Universal Soldier" (which also appears in the collection), it was written in the '60s. It rambles acoustically like an early Bob Dylan song, but the way Buffy holds up a mirror and eloquently conveys with emotion and sorrow how Canada has treated Indigenous people is her own.

(True North)Over the course of 50-odd years, her songs have sustained relevancy so that if you place songs she wrote in the '60s alongside songs from the '90s, early 2000s and ones from today, they will resonate and sound powerfully of this moment. That's what Buffy does in concert, and also what she does here on her 19th album, Medicine Songs, which brings together songs that uplift as much as educate about the plight of Indigenous people and push back against the greedy, warmongering, environmentally destructive powers that be. And sometimes, as Buffy says, you can dance to it.

It's like a Buffy Sainte-Marie retrospective, only the older songs are re-recorded using her current instrumental preferences and selected for thematic relevance. Unlike her Polaris Prize-winning 2015 record Power in the Blood, there are no love songs; Medicine Songs is unflinching in its focus.

Sainte-Marie kicks Medicine Songs off in high gear with "You Got to Run (Spirit of the Wind)," a universal and uplifting stadium-ready collaboration with fellow Polaris Prize-winner Tanya Tagaq. She then moves on to "The War Racket," a bass-y, synth-laden staple of her current live set and a takedown of war-supporting billionaires and politicians.

From there, Medicine Songs moves into borrowing: from older Buffy albums, from the traditional songbook (patriotic 1910 song "America the Beautiful" features two new Sainte-Marie-written verses here) and, surprisingly, from the still quite recent Power in the Blood ("Carry It On," "Power in the Blood" and, in the downloadable bonus tracks, "Generation" join this group, sounding as though they've been unaltered from her last album's takes).

Sainte-Marie worked with Chris Birkett, one of the three producers on Power in the Blood, this time around, and for the most part they've managed to carry Sainte-Marie's older songs sonically into the present using her current equipment. Brushed-up versions of powwow vocal-laden "Starwalker" (from 1976's Up Where We Belong), "Little Wheel Spin and Spin" and "Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee" sound extra vital.

Interestingly, Sainte-Marie revisits a number of songs from 1992's Coincidence and Likely Stories — five, if you take into consideration the bonus material. Perhaps she thought that people may have missed that collection the first time around, and wanted to give these songs another opportunity. "You say silver burns a hole in your pocket and gold burns a hole in your soul / Well, uranium burns a hole in forever / It just gets out of control," she talk-sings on almost the almost spoken-word "The Priests of the Golden Bull."

Sainte-Marie can be a total rocker, but the most poignant moment on the album is arguably her raw public address-like folk song, "My Country 'Tis of Thy People You're Dying." Like "Universal Soldier" (which also appears in the collection), it was written in the '60s. It rambles acoustically like an early Bob Dylan song, but the way Buffy holds up a mirror and eloquently conveys with emotion and sorrow how Canada has treated Indigenous people is her own.