Beverly Glenn-Copeland has been patiently waiting for his audience to arrive. At age 76, the music he made decades earlier has only recently been rediscovered by a new generation of listeners who cherish its messages of equality, equanimity, and ongoing change.

Copeland has experienced his own feelings of renewal through a discovery of the term "transgender" as a way to understand himself in the mid-1990s. Though his jazz-inflected folk albums and electronic experiments failed to catch on commercially at the time of their release, a series of critically acclaimed reissues has inspired his joyful return to live performances. All eras of Copeland's discography are being celebrated with the release of Transmissions, a career-spanning compilation soaring from his 1970 debut LP to his first new song in 15 years.

Growing up in Philadelphia, Copeland's childhood home was filled with Chopin piano pieces played by his father and Black spiritual songs passed down by his mother. While Copeland dropped out of piano lessons as a teenager due to an inability to keep up with his dad, he still received a scholarship to attend McGill University's Faculty of Music. After representing Canada with a performance of German lieder singing at Montreal's World Fair in 1967, he decided to remain in his adopted home country.

The next two decades would find Copeland beginning his solo career with an album released by CBC Radio Canada, performing as a backing vocalist with Bruce Cockburn, and joining the casts of both Mr. Dressup and Sesame Street. Sadly, his struggles to identify as non-heteronormative without the language to describe it never allowed him to feel comfortable in the music industry or the world of children's television.

His next move was leaving the big city for the solitude of Ontario's Muskoka woods. In between shovelling snow, Copeland's interest in Star Trek and the advent of the personal computer inspired his DIY education in how to make electronic music. The astonishing result is 1986's Keyboard Fantasies, an album of soothing synth waves and shuddering drum machines guided by Copeland's meditative mantras. Self-released as a cassette, it sold a small portion of its several hundred copies, with the rest tucked away on the shelf and forgotten.

Keyboard Fantasies was unearthed by Japanese record collector Ryota Masuko in 2015, who emailed Copeland and asked to purchase his remaining cassettes. This caused a surge of excitement among labels spanning the globe, eventually resulting in its first vinyl reissues from Toronto's Invisible City Editions and Séance Centre. The domino effect then led to Copeland's return to the stage for the first time in decades at SappyFest 2017, followed by the formation of his backing band of young Halifax musicians, Indigo Rising. That group's European tour became the focal point of a documentary, also called Keyboard Fantasies, and has been immortalized by their album recorded onstage in Utrecht, Live at Le Guess Who?

Copeland's international travels in the past few years have introduced him to high-profile fans including Robyn and Blood Orange's Dev Hynes. Caribou's Dan Snaith has described Keyboard Fantasies as a primary influence on his latest album, Suddenly. "Listening to Glenn's music, I heard a way of taking things that are difficult and making something positive, affirming, reassuring, and comforting out of them," Snaith told NPR. "That's what I tried to find in the music that I made."

Despite COVID-19 bringing his touring plans to a halt, 2020 will still be the year that introduces Copeland's music to an even wider international audience, thanks to his signing to London's Transgressive Records. The pandemic also left him and his wife Elizabeth homeless, with loving fans coming to their rescue by raising over $90,000 through a crowdfunding campaign.

To accompany the release of Transmissions, Exclaim! spoke with Copeland about the highs and lows of his truly fascinating trajectory.

Breaking Barriers at McGill

In 1961, Copeland was accepted to McGill University as the first Black student in their Faculty of Music. As he explains, this didn't cause any personal issues because there were many other Black students on campus. Rather than majoring in one subject with a mix of other classes, the core studies of his faculty were laser-focused on music. The small group of 20 students in his program would go on to become successful jazz musicians, classical composers, or lead universities themselves.

"The university couldn't care less, because musicians are crazy anyway — let's face it!" Copeland laughs now over the phone from his home in New Brunswick. "It was a phenomenal group, and they all became dynamos. I was totally comfortable in that environment. None of them even blinked."

What did cause an issue was Copeland's lesbian relationship while living in an all-women residence. Many of the younger students surrounding him at the time who had arrived at McGill from various places around the world were not used to sharing space with non-heternormative couples.

"This was 1961, but it was 1902 as far as we were concerned," says Copeland. "I was comfortable living with a girlfriend in the residence for five years, but other people weren't because we were totally out. It also freaked out the Assistant Dean of Women at the University. She got on a case to try to have me thrown out of McGill. Luckily, the Dean of Women who was overtop of her was very protective of me."

Children's TV Star

Following the release of Copeland's first two solo albums, he was approached by a writer on the children's TV show Mr. Dressup. She asked if the musician could be written into the script, and if Copeland would write a song tailored to his performance. On YouTube, viewers can see his large trademark glasses topped off with a pirate's hat and gold cape while playing keyboard for a puppet.

This led to Copeland's work on the show for more than 20 years, either acting or writing songs for other performers, alongside similar cameos on Sesame Street. While he loved relating directly to children and enjoyed the amorphous nature of dressing up in costumes, the experience came with its own personal difficulties.

"I knew I wasn't heternormative but I had to act as a female and fudge it in that direction," says Copeland. "I was referred to as 'her' all the time, and somewhere inside that made me very uncomfortable. Discussing being non-heteronormative in the environment of a children's show was just not a reality at that time. It didn't take away from that fact that I was enjoying it, but there were deeper psychological stresses going on at the same time."

Gender Transition

One day in 1995, Copeland was reading a book on the beach when he was struck by a lightning bolt of epiphany. He doesn't remember the title or author, but this book written in the 1970s used the term "transgender" in relation to their recollections of childhood.

"I sat up and said 'Oh my god, those are my memories!'" says Copeland. "You have to understand there were probably many people who were transgender at that time, but it was not a discussion in North America at all. Some of them had likely been married successfully in a heteronormative relationship for 30 years with children. Then one day a spouse would look at the other one and say, 'You know what? I'm you.'" One of the most moving sections of the documentary film Keyboard Fantasies shares the period Copeland spent with his mother after she learned to understand the term transgender as well.

"My mom accepted who I was from 1995 until 2006 when she passed away," says Copeland. "She had really been in my corner. It allowed us to have a deep and profound friendship. That was such a precious time for me, and for her too."

Rising from the Ashes in Phoenix

In the late 1990s, Copeland traveled to Phoenix, AZ, to stay with his mother, who had moved there to live by herself. During this trip, he suffered from a rare condition of twisted bowel obstruction, which he says leads to death from septicemia (bloodstream infection) in 50 per cent of cases. After being rushed to the hospital, Copeland could do little more than shake uncontrollably from his severe pain. The only thing that woke him from this state was a friend from his Buddhist organization standing by his bedside while loudly chanting.

"At the same moment that I woke up, a nurse came in and said they were going to take me in for exploratory surgery the next morning," says Copeland. "I said, 'Well, I'll be dead before then.' The colour drained out of her face, and they were wheeling me into an operation 15 minutes later. When I woke up from the drugs they had given me, the surgeon was leaning over my face, and he said, 'You were one sick puppy.'"

While he was under anesthesia during this life-saving surgery, Copeland says he received a message that "the universe is love." It inspired him to release his 2004 album Primal Prayer under the artist named Phynix (pronounced 'Phoenix'). "There were things in my life that I could understand more clearly," he says. "When I wrote that album I realized that, like a phoenix, I had risen from my own ashes."

That Time He Suddenly Knew How to Speak Italian

Copeland believes his music comes from the universe itself, arriving in his mind through an unconscious channel he calls "the Universal Broadcasting System." While recording Primal Prayer — a collection of devotional songs that combines jazz, trip-hop and breakbeats with operatic vocals — he miraculously wrote some of its lyrics in fluent Italian. This strikes him as especially odd because he had flunked first year courses in the language at McGill and never learned how to speak it.

"Scientists have said that we only use 6 per cent of our brain, so what's the other 94 per cent doing?" wonders Copeland. "What does it know and what is it recording? We don't yet know how to access it, except in dreams. Goodness knows what's really going on."

His Long Overdue Rise to Fame

The term "cult following" has often been used to describe Copeland's new audience. However, he believes they can more simply be called "young people." In the early 1980s, he was introduced to the prophecy of Indigo Children, a generation born that decade who would cultivate an empathetic understanding of humanity that had not previously existed.

"This is the age group of people who like my music," says Copeland. "They think of themselves as global citizens who act locally around those beliefs. They feel that compassion for people is a universal right, much less something we should cultivate. People around the world are essentially the same in their needs, and we need to develop a world culture that honours what it is humans really need: being safe, having food, and having the right to their culture. I didn't think of it as a cult. These were just the people who were supposed to show up." The 2015 reappraisal of Keyboard Fantasies helped to spread Copeland's music to this new, younger audience.

Since the advent of the internet, Copeland has also been impressed by the way his new fans break down borders in their listening habits. This allows them to appreciate how his music has always defied genre categorization, whether it's propelled by jazz drumming, hand drums or drum machines. "The new generations like music from all around the world," he says. "Before that, people in the music industry thought they should limit things to names like R&B, jazz and country. They marketed everything that way because it's how people listened to music, but now people listen to everything!"

Return to the Stage

Prior to his 2017 set at the SappyFest music festival in Sackville, NB (where he was living at the time), Copeland had only made one other onstage appearance since the 1980s. He had always been more interested in the process of making music than performing it. When he stepped out from the curtains at the Vogue Cinema and saw a younger crowd in its rows of seats, he felt a renewed sense of purpose.

"I wanted to talk to the audience for the first time," says Copeland. "It's almost like I had never been on stage before with that spiritual and emotional attitude. One, I needed to thank the audience. And two, I needed to talk to people. My music is about who we're trying to be as humans on this particular planet. I can finally talk about that with the audience understanding what I'm saying, because they're saying the same things!"

Copeland's stage banter is often the highlight of his performances, sometimes extending to 10 minutes between songs with his charismatic jokes, explanations of lyrics, and heartfelt recollections. He believes that an understanding of how changes are happening (both to people and the natural world) has evolved significantly, and it is now his responsibility as an elder to support the actions of the youth.

"I was told by young people how they were judged as being losers by their own parents," he says. "Parents want their children to thrive and survive, but don't understand what changes have happened on a deep level to make things relevant to the new society, which is now smacking us in the face. They also weren't hip to the fact that the Earth is dying, but they're getting it now because of the new generation. Things are escalating at a tremendous pace."

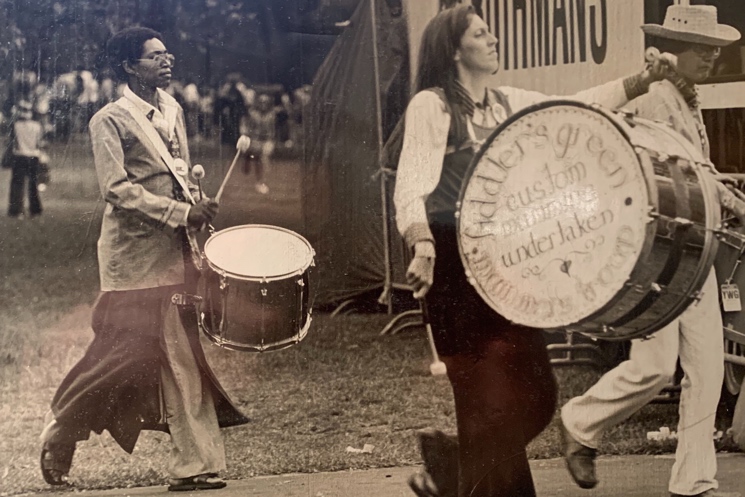

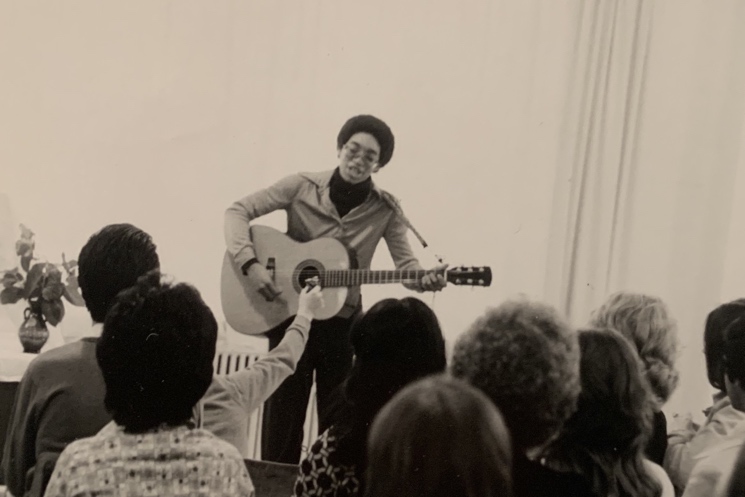

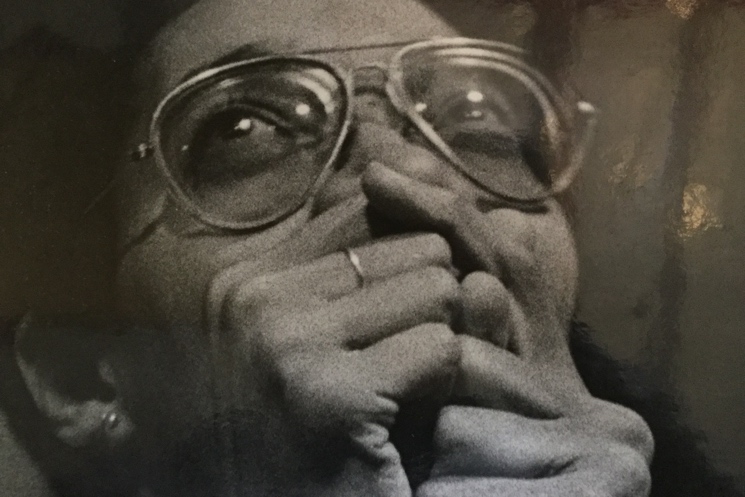

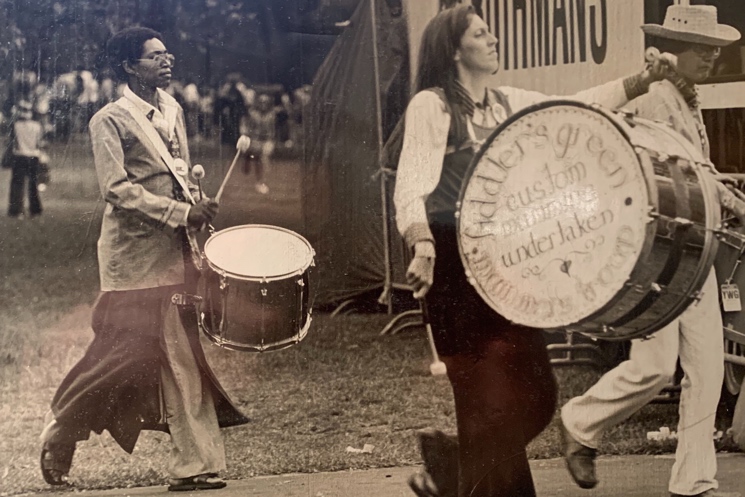

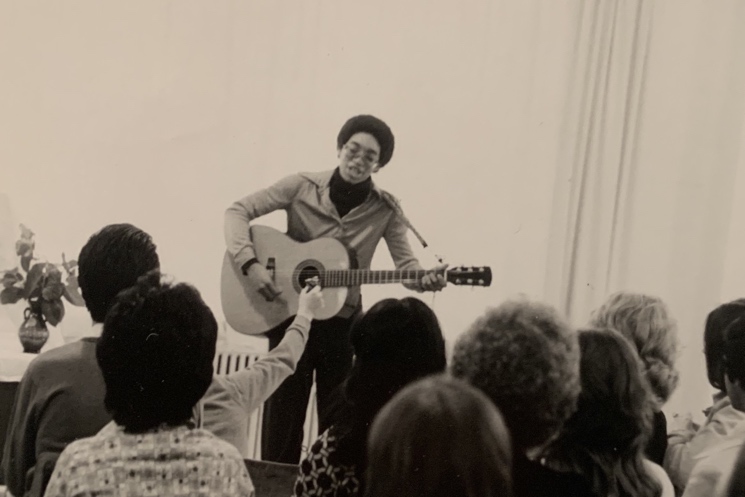

Photo: Amus Osaurus

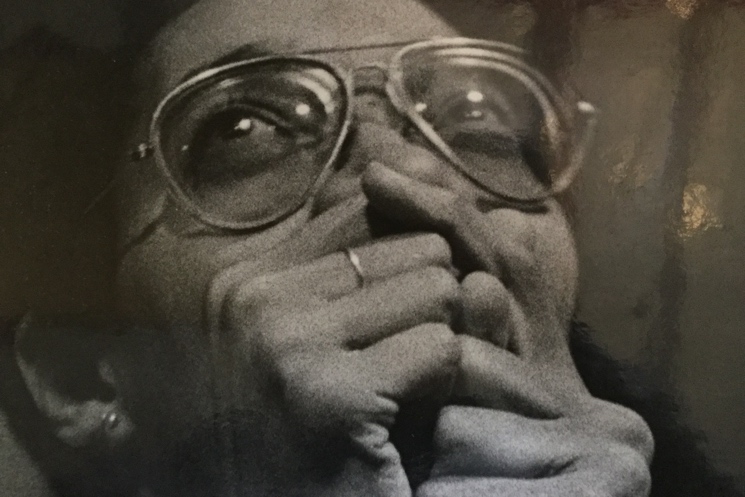

Photo: Amus Osaurus

Fans Come to His Aid During the Pandemic

In November 2019, before the worldwide impacts of COVID-19 had become clear, Copeland and his wife Elizabeth sold their home in Sackville. They had planned to purchase a new house in Quebec, but when the pandemic caused an end to his touring plans for the year ahead (alongside their source of income), the bank loan required suddenly became an impossibility. Sadly, they had already put the wheels in motion for their Sackville home to be vacated in spring 2020, leaving them without a roof over their heads.

"Elizabeth is a major artist in several different disciplines, and she's also an incredible communicator," says Copeland. "She wrote something like 800 emails over the course of a bunch of months to let people know we were in desperate straits. Half of my fanbase knew about it, and then my daughter decided it would be a good idea to start a crowdfunding platform. That came to the attention of a CBC reporter who lived around the corner from us. We did an interview that got televised, and people started sending money like crazy."

Primarily through increments of $15 or $20, Copeland's GoFundMe campaign ended up raising $91,676. The CBC interview also brought their predicament to the attention of a couple who made their fortune as lawyers earlier in life. They offered one of their homes in rural New Brunswick to the stranded couple for as long as they need before they move elsewhere, which the Copelands currently plan to do in spring 2021. The generosity they have experienced is yet another testament to the way Copeland's music leaves a deep impact on anyone who hears it.

"When something like this happens with people going from compassionate on the inside about something you read about, to being compassionate about you, it's life-changing," says Copeland. "If you ever thought it was theoretical, here's proof. We had never been in need of that kind of compassion, but suddenly, blam! Here it was. I'm changed forever. It's proof of the way the new generations think and their commitment to a world family."

Copeland has experienced his own feelings of renewal through a discovery of the term "transgender" as a way to understand himself in the mid-1990s. Though his jazz-inflected folk albums and electronic experiments failed to catch on commercially at the time of their release, a series of critically acclaimed reissues has inspired his joyful return to live performances. All eras of Copeland's discography are being celebrated with the release of Transmissions, a career-spanning compilation soaring from his 1970 debut LP to his first new song in 15 years.

Growing up in Philadelphia, Copeland's childhood home was filled with Chopin piano pieces played by his father and Black spiritual songs passed down by his mother. While Copeland dropped out of piano lessons as a teenager due to an inability to keep up with his dad, he still received a scholarship to attend McGill University's Faculty of Music. After representing Canada with a performance of German lieder singing at Montreal's World Fair in 1967, he decided to remain in his adopted home country.

The next two decades would find Copeland beginning his solo career with an album released by CBC Radio Canada, performing as a backing vocalist with Bruce Cockburn, and joining the casts of both Mr. Dressup and Sesame Street. Sadly, his struggles to identify as non-heteronormative without the language to describe it never allowed him to feel comfortable in the music industry or the world of children's television.

His next move was leaving the big city for the solitude of Ontario's Muskoka woods. In between shovelling snow, Copeland's interest in Star Trek and the advent of the personal computer inspired his DIY education in how to make electronic music. The astonishing result is 1986's Keyboard Fantasies, an album of soothing synth waves and shuddering drum machines guided by Copeland's meditative mantras. Self-released as a cassette, it sold a small portion of its several hundred copies, with the rest tucked away on the shelf and forgotten.

Keyboard Fantasies was unearthed by Japanese record collector Ryota Masuko in 2015, who emailed Copeland and asked to purchase his remaining cassettes. This caused a surge of excitement among labels spanning the globe, eventually resulting in its first vinyl reissues from Toronto's Invisible City Editions and Séance Centre. The domino effect then led to Copeland's return to the stage for the first time in decades at SappyFest 2017, followed by the formation of his backing band of young Halifax musicians, Indigo Rising. That group's European tour became the focal point of a documentary, also called Keyboard Fantasies, and has been immortalized by their album recorded onstage in Utrecht, Live at Le Guess Who?

Copeland's international travels in the past few years have introduced him to high-profile fans including Robyn and Blood Orange's Dev Hynes. Caribou's Dan Snaith has described Keyboard Fantasies as a primary influence on his latest album, Suddenly. "Listening to Glenn's music, I heard a way of taking things that are difficult and making something positive, affirming, reassuring, and comforting out of them," Snaith told NPR. "That's what I tried to find in the music that I made."

Despite COVID-19 bringing his touring plans to a halt, 2020 will still be the year that introduces Copeland's music to an even wider international audience, thanks to his signing to London's Transgressive Records. The pandemic also left him and his wife Elizabeth homeless, with loving fans coming to their rescue by raising over $90,000 through a crowdfunding campaign.

To accompany the release of Transmissions, Exclaim! spoke with Copeland about the highs and lows of his truly fascinating trajectory.

Breaking Barriers at McGill

In 1961, Copeland was accepted to McGill University as the first Black student in their Faculty of Music. As he explains, this didn't cause any personal issues because there were many other Black students on campus. Rather than majoring in one subject with a mix of other classes, the core studies of his faculty were laser-focused on music. The small group of 20 students in his program would go on to become successful jazz musicians, classical composers, or lead universities themselves.

"The university couldn't care less, because musicians are crazy anyway — let's face it!" Copeland laughs now over the phone from his home in New Brunswick. "It was a phenomenal group, and they all became dynamos. I was totally comfortable in that environment. None of them even blinked."

What did cause an issue was Copeland's lesbian relationship while living in an all-women residence. Many of the younger students surrounding him at the time who had arrived at McGill from various places around the world were not used to sharing space with non-heternormative couples.

"This was 1961, but it was 1902 as far as we were concerned," says Copeland. "I was comfortable living with a girlfriend in the residence for five years, but other people weren't because we were totally out. It also freaked out the Assistant Dean of Women at the University. She got on a case to try to have me thrown out of McGill. Luckily, the Dean of Women who was overtop of her was very protective of me."

Children's TV Star

Following the release of Copeland's first two solo albums, he was approached by a writer on the children's TV show Mr. Dressup. She asked if the musician could be written into the script, and if Copeland would write a song tailored to his performance. On YouTube, viewers can see his large trademark glasses topped off with a pirate's hat and gold cape while playing keyboard for a puppet.

This led to Copeland's work on the show for more than 20 years, either acting or writing songs for other performers, alongside similar cameos on Sesame Street. While he loved relating directly to children and enjoyed the amorphous nature of dressing up in costumes, the experience came with its own personal difficulties.

"I knew I wasn't heternormative but I had to act as a female and fudge it in that direction," says Copeland. "I was referred to as 'her' all the time, and somewhere inside that made me very uncomfortable. Discussing being non-heteronormative in the environment of a children's show was just not a reality at that time. It didn't take away from that fact that I was enjoying it, but there were deeper psychological stresses going on at the same time."

Gender Transition

One day in 1995, Copeland was reading a book on the beach when he was struck by a lightning bolt of epiphany. He doesn't remember the title or author, but this book written in the 1970s used the term "transgender" in relation to their recollections of childhood.

"I sat up and said 'Oh my god, those are my memories!'" says Copeland. "You have to understand there were probably many people who were transgender at that time, but it was not a discussion in North America at all. Some of them had likely been married successfully in a heteronormative relationship for 30 years with children. Then one day a spouse would look at the other one and say, 'You know what? I'm you.'" One of the most moving sections of the documentary film Keyboard Fantasies shares the period Copeland spent with his mother after she learned to understand the term transgender as well.

"My mom accepted who I was from 1995 until 2006 when she passed away," says Copeland. "She had really been in my corner. It allowed us to have a deep and profound friendship. That was such a precious time for me, and for her too."

Rising from the Ashes in Phoenix

In the late 1990s, Copeland traveled to Phoenix, AZ, to stay with his mother, who had moved there to live by herself. During this trip, he suffered from a rare condition of twisted bowel obstruction, which he says leads to death from septicemia (bloodstream infection) in 50 per cent of cases. After being rushed to the hospital, Copeland could do little more than shake uncontrollably from his severe pain. The only thing that woke him from this state was a friend from his Buddhist organization standing by his bedside while loudly chanting.

"At the same moment that I woke up, a nurse came in and said they were going to take me in for exploratory surgery the next morning," says Copeland. "I said, 'Well, I'll be dead before then.' The colour drained out of her face, and they were wheeling me into an operation 15 minutes later. When I woke up from the drugs they had given me, the surgeon was leaning over my face, and he said, 'You were one sick puppy.'"

While he was under anesthesia during this life-saving surgery, Copeland says he received a message that "the universe is love." It inspired him to release his 2004 album Primal Prayer under the artist named Phynix (pronounced 'Phoenix'). "There were things in my life that I could understand more clearly," he says. "When I wrote that album I realized that, like a phoenix, I had risen from my own ashes."

That Time He Suddenly Knew How to Speak Italian

Copeland believes his music comes from the universe itself, arriving in his mind through an unconscious channel he calls "the Universal Broadcasting System." While recording Primal Prayer — a collection of devotional songs that combines jazz, trip-hop and breakbeats with operatic vocals — he miraculously wrote some of its lyrics in fluent Italian. This strikes him as especially odd because he had flunked first year courses in the language at McGill and never learned how to speak it.

"Scientists have said that we only use 6 per cent of our brain, so what's the other 94 per cent doing?" wonders Copeland. "What does it know and what is it recording? We don't yet know how to access it, except in dreams. Goodness knows what's really going on."

His Long Overdue Rise to Fame

The term "cult following" has often been used to describe Copeland's new audience. However, he believes they can more simply be called "young people." In the early 1980s, he was introduced to the prophecy of Indigo Children, a generation born that decade who would cultivate an empathetic understanding of humanity that had not previously existed.

"This is the age group of people who like my music," says Copeland. "They think of themselves as global citizens who act locally around those beliefs. They feel that compassion for people is a universal right, much less something we should cultivate. People around the world are essentially the same in their needs, and we need to develop a world culture that honours what it is humans really need: being safe, having food, and having the right to their culture. I didn't think of it as a cult. These were just the people who were supposed to show up." The 2015 reappraisal of Keyboard Fantasies helped to spread Copeland's music to this new, younger audience.

Since the advent of the internet, Copeland has also been impressed by the way his new fans break down borders in their listening habits. This allows them to appreciate how his music has always defied genre categorization, whether it's propelled by jazz drumming, hand drums or drum machines. "The new generations like music from all around the world," he says. "Before that, people in the music industry thought they should limit things to names like R&B, jazz and country. They marketed everything that way because it's how people listened to music, but now people listen to everything!"

Return to the Stage

Prior to his 2017 set at the SappyFest music festival in Sackville, NB (where he was living at the time), Copeland had only made one other onstage appearance since the 1980s. He had always been more interested in the process of making music than performing it. When he stepped out from the curtains at the Vogue Cinema and saw a younger crowd in its rows of seats, he felt a renewed sense of purpose.

"I wanted to talk to the audience for the first time," says Copeland. "It's almost like I had never been on stage before with that spiritual and emotional attitude. One, I needed to thank the audience. And two, I needed to talk to people. My music is about who we're trying to be as humans on this particular planet. I can finally talk about that with the audience understanding what I'm saying, because they're saying the same things!"

Copeland's stage banter is often the highlight of his performances, sometimes extending to 10 minutes between songs with his charismatic jokes, explanations of lyrics, and heartfelt recollections. He believes that an understanding of how changes are happening (both to people and the natural world) has evolved significantly, and it is now his responsibility as an elder to support the actions of the youth.

"I was told by young people how they were judged as being losers by their own parents," he says. "Parents want their children to thrive and survive, but don't understand what changes have happened on a deep level to make things relevant to the new society, which is now smacking us in the face. They also weren't hip to the fact that the Earth is dying, but they're getting it now because of the new generation. Things are escalating at a tremendous pace."

Photo: Amus Osaurus

Photo: Amus OsaurusFans Come to His Aid During the Pandemic

In November 2019, before the worldwide impacts of COVID-19 had become clear, Copeland and his wife Elizabeth sold their home in Sackville. They had planned to purchase a new house in Quebec, but when the pandemic caused an end to his touring plans for the year ahead (alongside their source of income), the bank loan required suddenly became an impossibility. Sadly, they had already put the wheels in motion for their Sackville home to be vacated in spring 2020, leaving them without a roof over their heads.

"Elizabeth is a major artist in several different disciplines, and she's also an incredible communicator," says Copeland. "She wrote something like 800 emails over the course of a bunch of months to let people know we were in desperate straits. Half of my fanbase knew about it, and then my daughter decided it would be a good idea to start a crowdfunding platform. That came to the attention of a CBC reporter who lived around the corner from us. We did an interview that got televised, and people started sending money like crazy."

Primarily through increments of $15 or $20, Copeland's GoFundMe campaign ended up raising $91,676. The CBC interview also brought their predicament to the attention of a couple who made their fortune as lawyers earlier in life. They offered one of their homes in rural New Brunswick to the stranded couple for as long as they need before they move elsewhere, which the Copelands currently plan to do in spring 2021. The generosity they have experienced is yet another testament to the way Copeland's music leaves a deep impact on anyone who hears it.

"When something like this happens with people going from compassionate on the inside about something you read about, to being compassionate about you, it's life-changing," says Copeland. "If you ever thought it was theoretical, here's proof. We had never been in need of that kind of compassion, but suddenly, blam! Here it was. I'm changed forever. It's proof of the way the new generations think and their commitment to a world family."