After spending years delving into Buffy Sainte-Marie's pan-genre discography — seriously, she's done it all, and she's done it better than most — there's no good reason why Sainte-Marie shouldn't receive the same level of worldwide recognition and acclaim as Neil Young and Joni Mitchell. Why isn't she revered as a powerhouse, like Janis Joplin, or as the voice of the folk movement, like Bob Dylan? Systemic racism has played its part; Sainte-Marie, a Canadian-born Cree woman who was raised in America, has always used music as a tool of passion, protest, advocacy, resistance and decolonization.

All of the things that folkies were supposedly singing about and protesting, Sainte-Marie sang those things, too, but she went deeper, digging in and uprooting the sources of disenfranchisement: white supremacy, patriarchy, racism, sexism, colonization. Massive inequality is, or should be, a universal concept. But even if record executives and music fans were put off by her political side, Sainte-Marie also tackled all the "softer" things, too: love and loss, sex and desire, grief and joy were common thematic explorations of hers, and they co-existed alongside narratives of protest, Indigenous identity — past and present — and Native American rights, of folklore and nature and spirituality, and all the metaphors between heaven and hell.

The thrilling thing about a Sainte-Marie record, particularly through the late '60s, '70s and this decade, is the multiplicity of possibilities, the vast wilderness of Sainte-Marie's interests and influences, and her fearless cross-genre experimentation. Despite two lengthy breaks from recording, from 1976 to 1992 and then again from 1992 to 2008, Sainte-Marie's career spans more than 50 years. So, where to start? Well, how about right here, with Exclaim!'s Essential Guide to Buffy Sainte-Marie.

Essential Albums:

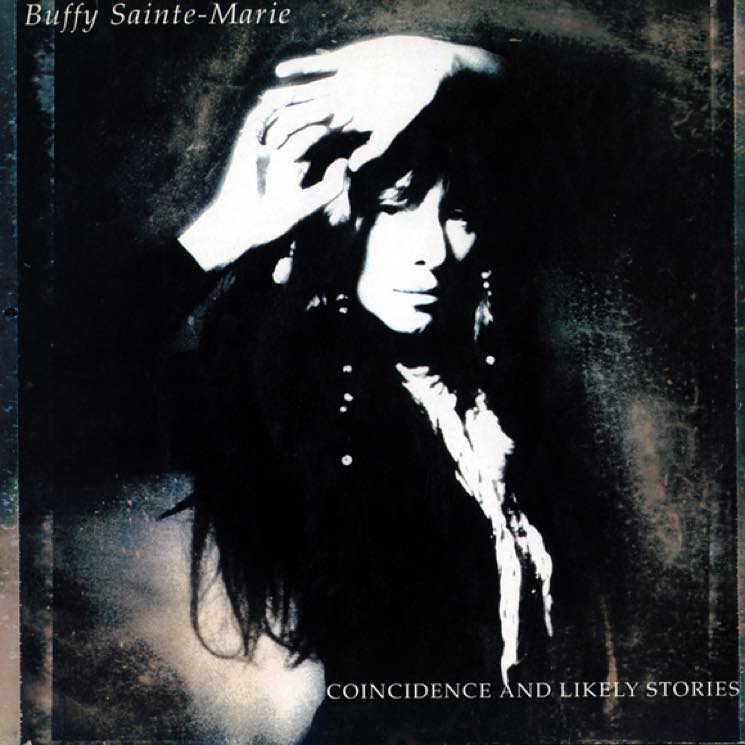

5. Coincidence and Likely Stories

(1992)

Sainte-Marie's prolonged hiatus from the recording industry was, at first, a chosen one, but eventually became a sort-of exile. In 1976, she wanted to focus on raising her young son. She stopped touring and joined Sesame Street for five years. Eventually, she learned that she had been blacklisted from radio, and though it didn't stop her from winning an Academy Award in 1983 for her song, "Up Where We Belong," from An Officer and a Gentleman, she felt ii definitely prevented her from more mainstream success.

Coincidence and Likely Stories became Sainte-Marie's big comeback — or, at least, her first one. It's a mash-up of her major interests and influences, picking up where she left off with her experiments with electronic music, powwow (Sainte-Marie says she was the first person to use Indigenous beats in mainstream rock with her 1976 song, "Starwalker") and folk. The album features a few songs that are steeped in '80s-style production ("The Big Ones Get Away," "Fallen Angels") and at least one slinky, sexy, sax-heavy track ("Emma Lee"), but the rest of the songs are galvanized by her fusion of synths and powwow beats, including an extended and thrilling version of "Starwalker," the powerful anthem "I'm Going Home" and vibrant protest number "Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee," a living history lesson from the early '80s about Native American rights versus corporate interests.

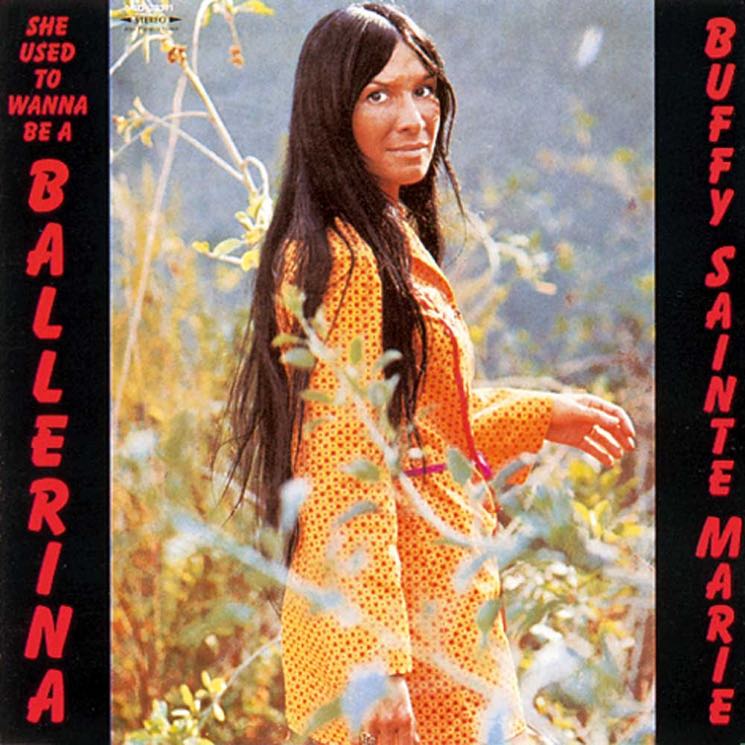

4. She Used to Wanna Be a Ballerina

(1971)

Following the commercial failure of Illuminations, Sainte-Marie re-embraced the folk-rock sound she'd helped establish as the prevailing style of the '60s and early '70s, but she also continued to innovate and disregard conventional rules of album sequencing, pivoting purposefully from piano pop ("Smack Water," a Carol King cover) to rollicking anthems (the title track) to damning war protest jams ("Moratorium").

The soaring chorus and melody on standout "Sweet September Morning" show just how much Sainte-Marie was developing as a pop songwriter: "He finds them by the roadside / And he gives them his hands / And he breaks his love before them / And he feeds and he knows what he knows / Like the trees do / And he grows when he grows / When he needs you to." She was also adept at taking famous songs and making them her own, including a gentle and generous interpretation of Leonard Cohen's "Bells" and a glorious, soulful rendition of Neil Young's "Helpless," two love letters to her peers, fellow Canadian poets putting verse to music.

3. Power in the Blood

(2015)

One of the best records of 2015, Power in the Blood was only Sainte-Marie's second record since 1992's Coincidence and Likely Stories. A thrilling, vital and visceral experience, the album is both a full circle on the first 50 years of Sainte-Marie's extraordinary career and a signal of what her path forward could look like. Technology caught up to Sainte-Marie's spirit of innovation, but her sense of play, exploration and discovery is as vibrant at 74 as it was at 24.

The opening track is a cover of her own hit, "It's My Way," a more assertive and electric version of the song that asserted her agency and arrival in 1964. The title track follows, a cover of Alabama 3's "Power in the Blood," but in Sainte-Marie's hands, it's a total reinvention. She turns the song into a throbbing club banger, adding verses to make it a scathing anti-war statement with a dance-heavy beat. "We Are Circling" combines a great, steady drum roll with chanting and a catchy melody to intoxicating effect, like an incantation of joy, or a prayer of celebration.

"La Sakihitin Awasis (I Love You, Baby)" is devastating and dreamy. "It's the fifth generation," Sainte-Marie sings, "the young and the old are as one / singing come back to the sweet grass and the pipe and the drum." It's a marked contrast, yet wonderful companion, to the sweetest, simplest love song Sainte-Marie's ever penned, "Farm in the Middle of Nowhere." The album ends with the environmental anthem "Carry It On," a sing-along of a song that remains hopeful, upbeat and defiant, even as Sainte-Marie sings ruefully, "You can see we're only here by the skin of our teeth." Still, she urges us forward, encourages the listener to be better, to "take heart" and, of course, to "carry it on."

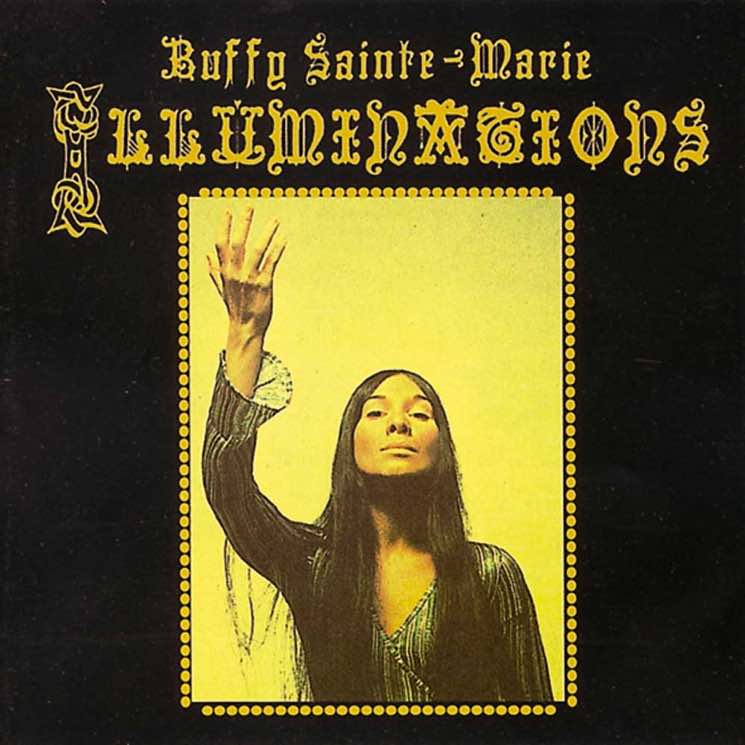

2. Illuminations

(1969)

A lot of great artists have that record where they throw caution to the wind and go experimental. Sometimes it comes off as indulgent; other times, it's unrestrained genius. Illuminations falls firmly on the side of the latter, even though it was something of a commercial disaster when it was first released. Now, it's lauded by critics and technology nerds, and considered among the earliest works prominently featuring electronic synthesizers, with Sainte-Marie going so far as to alter her vocals through a Buchla.

For all the tech trappings, Illuminations is also quite devotional; several of the songs directly reference religion and/or spirituality, including a cover of Leonard Cohen's "God is Alive, Magic is Afoot," the mournful "Mary," the trippy, psych-rock dirge "Adam" and the heavy orchestral ballad "The Angel." These are also the tracks that feature electronic experimentation most prominently, as Sainte-Marie creates a tangible relationship between the digital and esoteric with every droning buzz, slyly playing with our concepts of what's real, what's faith and where the two intersect.

In addition to the awe-inspiring weirdness on this record, there's also proof that Sainte-Marie had been pigeonholed as an activist folkie; but not enough people were paying attention to her burgeoning psych-rock and art-rock sides. "He's a Keeper of the Fire" features a Sainte-Marie vocal performance easily on par with Janis Joplin, while "Poppies" starts softly before evolving into something akin to operetta. It's one of her most daring, visceral, haunting performances, and it's easy to hear how this influenced Sarah McLachlan's earliest, more experimental recordings.

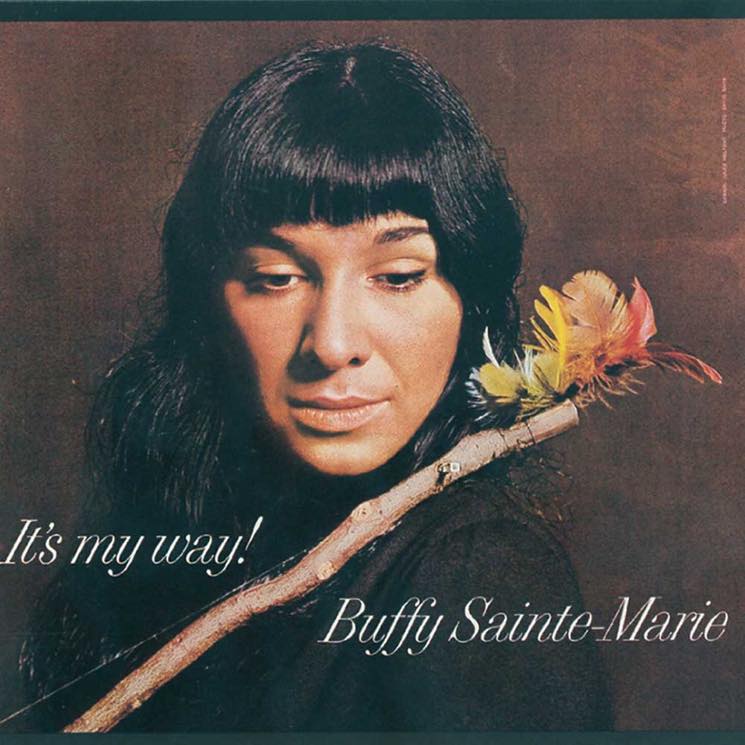

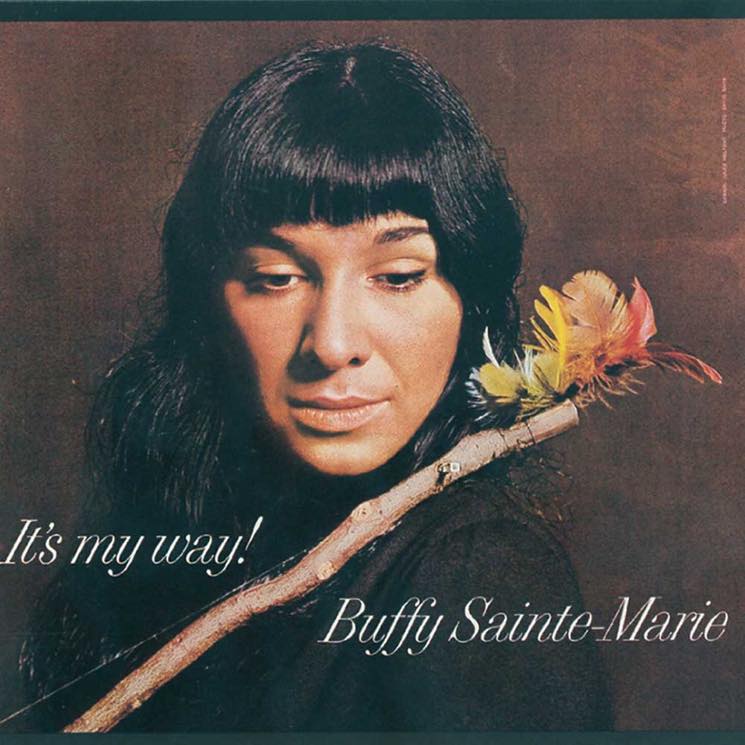

1. It's My Way!

(1964)

It didn't chart, but Buffy Sainte-Marie's debut record was so influential amongst her fellow folkies, and so covered by her community, its beating heart fuelled an entire generation of protest music. The very first song on Sainte-Marie's debut album, the way she announced her arrival, was a huge statement. "Now That the Buffalo's Gone" tore out the heart of the American dream — opportunity, capitalism, freedom — by reminding the country of its colonization, of stolen land and its brutal treatment of Native Americans. But the song's genius is in its framing, singing to the listener, an invisible "good lady and good man" and asking them to recognize the mistakes of the past, the broken treaties, and to help stand up for the modern Navajo Nation.

Throughout the song, Sainte-Marie's voice morphs from gentle and assertive to powerful and thundering. Her vocal performance was a revelation then and has continued to impress with its ability to shape-shift as necessary. It's My Way! offered a taste of Sainte-Marie's future status as an icon. She's an epic performer, occasionally dipping into her cavernous vibrato or employing diamond-like clarity and refracted sparkle when she's at her most joyful, and the songs are so varied — Irish folk tunes ("Old Man's Lament"), gritty gospel ("Ananais"), blood-chilling blues ("Cod'ine"), twang-filled Appalachian ("Cripple Creek") and fiery folk anthems ("Universal Soldier", "It's My Way") — that the only real common denominator is Sainte-Marie. Here, in her desire to explore humanity to its fullest, she presents the most cohesive map of North America that music fans had ever seen to this point.

What to Avoid:

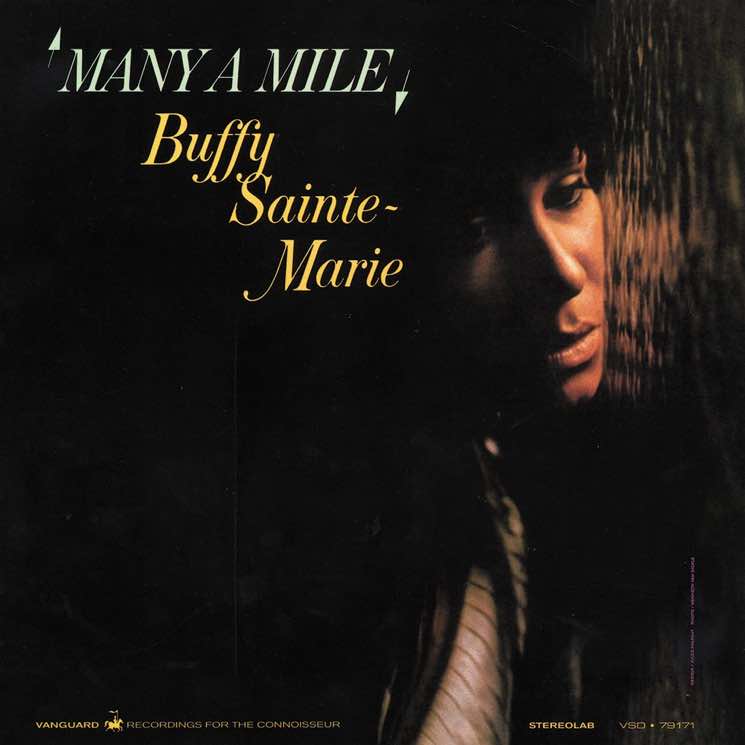

Sainte-Marie was prolific in the first 12 years of her career, releasing a new record almost annually. Her sophomore effort, 1965's Many a Mile, isn't by any means bad, but it's not quite as good as her debut, or the album that followed it, 1966's Little Wheel Spin and Spin. It does feature one major standout, Sainte-Marie's most covered song, "Until It's Time for You To Go." This mournful ballad is among her best songwriting, and everybody from Elvis to Streisand have taken it into their repertoire. It's gorgeous and tender, and never more so than in Sainte-Marie's no-nonsense vibrato, which somehow convincingly straddles the line between heartbroken vulnerability and steely determination.

1973's Quiet Places is unremarkable other than being her last album for her longtime label, Vanguard, while 1975's Changing Woman is so sincere it occasionally borders on excruciating.

Further Listening:

Listen to it all. Even though Sainte-Marie's career has spanned a half-century, her significant breaks mean that her discography isn't overwhelmingly large.

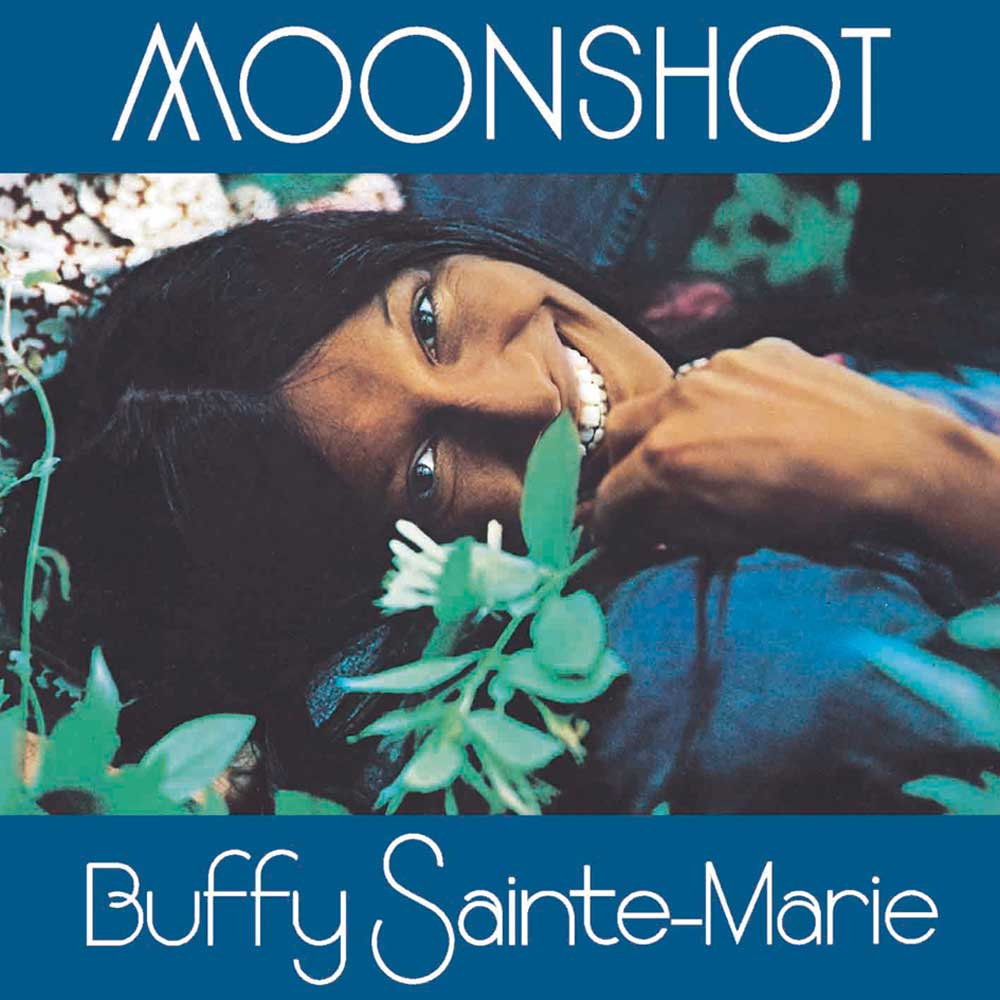

But if you need a few other places to start, dig into 1972's Moonshot, which is filled with all sorts of era-specific flourishes, yet also feels timeless. Her voice is an avalanche in the brilliant fuck-you rocker, "Not the Lovin' Kind," and blooms like soft petals on the flowery "I Wanna Hold Your Hand Forever" before kicking up the spurs on honky-tonk gem "My Baby Left Me." The title track itself is a thing of wonder; spacey and tense, it's a total trip on every level, tightly packed with strange arrangements.

Her greatest hits package in 1996, Up Where We Belong, is a decent survey of some of Sainte-Marie's most popular songs. It's also a wonderful opportunity to listen to her own interpretation of her Academy Award-winning title track, a completely different (and more satisfying) delivery that truly earns the triumphant swell of that infamous chorus.

All of the things that folkies were supposedly singing about and protesting, Sainte-Marie sang those things, too, but she went deeper, digging in and uprooting the sources of disenfranchisement: white supremacy, patriarchy, racism, sexism, colonization. Massive inequality is, or should be, a universal concept. But even if record executives and music fans were put off by her political side, Sainte-Marie also tackled all the "softer" things, too: love and loss, sex and desire, grief and joy were common thematic explorations of hers, and they co-existed alongside narratives of protest, Indigenous identity — past and present — and Native American rights, of folklore and nature and spirituality, and all the metaphors between heaven and hell.

The thrilling thing about a Sainte-Marie record, particularly through the late '60s, '70s and this decade, is the multiplicity of possibilities, the vast wilderness of Sainte-Marie's interests and influences, and her fearless cross-genre experimentation. Despite two lengthy breaks from recording, from 1976 to 1992 and then again from 1992 to 2008, Sainte-Marie's career spans more than 50 years. So, where to start? Well, how about right here, with Exclaim!'s Essential Guide to Buffy Sainte-Marie.

Essential Albums:

5. Coincidence and Likely Stories

(1992)

Sainte-Marie's prolonged hiatus from the recording industry was, at first, a chosen one, but eventually became a sort-of exile. In 1976, she wanted to focus on raising her young son. She stopped touring and joined Sesame Street for five years. Eventually, she learned that she had been blacklisted from radio, and though it didn't stop her from winning an Academy Award in 1983 for her song, "Up Where We Belong," from An Officer and a Gentleman, she felt ii definitely prevented her from more mainstream success.

Coincidence and Likely Stories became Sainte-Marie's big comeback — or, at least, her first one. It's a mash-up of her major interests and influences, picking up where she left off with her experiments with electronic music, powwow (Sainte-Marie says she was the first person to use Indigenous beats in mainstream rock with her 1976 song, "Starwalker") and folk. The album features a few songs that are steeped in '80s-style production ("The Big Ones Get Away," "Fallen Angels") and at least one slinky, sexy, sax-heavy track ("Emma Lee"), but the rest of the songs are galvanized by her fusion of synths and powwow beats, including an extended and thrilling version of "Starwalker," the powerful anthem "I'm Going Home" and vibrant protest number "Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee," a living history lesson from the early '80s about Native American rights versus corporate interests.

4. She Used to Wanna Be a Ballerina

(1971)

Following the commercial failure of Illuminations, Sainte-Marie re-embraced the folk-rock sound she'd helped establish as the prevailing style of the '60s and early '70s, but she also continued to innovate and disregard conventional rules of album sequencing, pivoting purposefully from piano pop ("Smack Water," a Carol King cover) to rollicking anthems (the title track) to damning war protest jams ("Moratorium").

The soaring chorus and melody on standout "Sweet September Morning" show just how much Sainte-Marie was developing as a pop songwriter: "He finds them by the roadside / And he gives them his hands / And he breaks his love before them / And he feeds and he knows what he knows / Like the trees do / And he grows when he grows / When he needs you to." She was also adept at taking famous songs and making them her own, including a gentle and generous interpretation of Leonard Cohen's "Bells" and a glorious, soulful rendition of Neil Young's "Helpless," two love letters to her peers, fellow Canadian poets putting verse to music.

3. Power in the Blood

(2015)

One of the best records of 2015, Power in the Blood was only Sainte-Marie's second record since 1992's Coincidence and Likely Stories. A thrilling, vital and visceral experience, the album is both a full circle on the first 50 years of Sainte-Marie's extraordinary career and a signal of what her path forward could look like. Technology caught up to Sainte-Marie's spirit of innovation, but her sense of play, exploration and discovery is as vibrant at 74 as it was at 24.

The opening track is a cover of her own hit, "It's My Way," a more assertive and electric version of the song that asserted her agency and arrival in 1964. The title track follows, a cover of Alabama 3's "Power in the Blood," but in Sainte-Marie's hands, it's a total reinvention. She turns the song into a throbbing club banger, adding verses to make it a scathing anti-war statement with a dance-heavy beat. "We Are Circling" combines a great, steady drum roll with chanting and a catchy melody to intoxicating effect, like an incantation of joy, or a prayer of celebration.

"La Sakihitin Awasis (I Love You, Baby)" is devastating and dreamy. "It's the fifth generation," Sainte-Marie sings, "the young and the old are as one / singing come back to the sweet grass and the pipe and the drum." It's a marked contrast, yet wonderful companion, to the sweetest, simplest love song Sainte-Marie's ever penned, "Farm in the Middle of Nowhere." The album ends with the environmental anthem "Carry It On," a sing-along of a song that remains hopeful, upbeat and defiant, even as Sainte-Marie sings ruefully, "You can see we're only here by the skin of our teeth." Still, she urges us forward, encourages the listener to be better, to "take heart" and, of course, to "carry it on."

2. Illuminations

(1969)

A lot of great artists have that record where they throw caution to the wind and go experimental. Sometimes it comes off as indulgent; other times, it's unrestrained genius. Illuminations falls firmly on the side of the latter, even though it was something of a commercial disaster when it was first released. Now, it's lauded by critics and technology nerds, and considered among the earliest works prominently featuring electronic synthesizers, with Sainte-Marie going so far as to alter her vocals through a Buchla.

For all the tech trappings, Illuminations is also quite devotional; several of the songs directly reference religion and/or spirituality, including a cover of Leonard Cohen's "God is Alive, Magic is Afoot," the mournful "Mary," the trippy, psych-rock dirge "Adam" and the heavy orchestral ballad "The Angel." These are also the tracks that feature electronic experimentation most prominently, as Sainte-Marie creates a tangible relationship between the digital and esoteric with every droning buzz, slyly playing with our concepts of what's real, what's faith and where the two intersect.

In addition to the awe-inspiring weirdness on this record, there's also proof that Sainte-Marie had been pigeonholed as an activist folkie; but not enough people were paying attention to her burgeoning psych-rock and art-rock sides. "He's a Keeper of the Fire" features a Sainte-Marie vocal performance easily on par with Janis Joplin, while "Poppies" starts softly before evolving into something akin to operetta. It's one of her most daring, visceral, haunting performances, and it's easy to hear how this influenced Sarah McLachlan's earliest, more experimental recordings.

1. It's My Way!

(1964)

It didn't chart, but Buffy Sainte-Marie's debut record was so influential amongst her fellow folkies, and so covered by her community, its beating heart fuelled an entire generation of protest music. The very first song on Sainte-Marie's debut album, the way she announced her arrival, was a huge statement. "Now That the Buffalo's Gone" tore out the heart of the American dream — opportunity, capitalism, freedom — by reminding the country of its colonization, of stolen land and its brutal treatment of Native Americans. But the song's genius is in its framing, singing to the listener, an invisible "good lady and good man" and asking them to recognize the mistakes of the past, the broken treaties, and to help stand up for the modern Navajo Nation.

Throughout the song, Sainte-Marie's voice morphs from gentle and assertive to powerful and thundering. Her vocal performance was a revelation then and has continued to impress with its ability to shape-shift as necessary. It's My Way! offered a taste of Sainte-Marie's future status as an icon. She's an epic performer, occasionally dipping into her cavernous vibrato or employing diamond-like clarity and refracted sparkle when she's at her most joyful, and the songs are so varied — Irish folk tunes ("Old Man's Lament"), gritty gospel ("Ananais"), blood-chilling blues ("Cod'ine"), twang-filled Appalachian ("Cripple Creek") and fiery folk anthems ("Universal Soldier", "It's My Way") — that the only real common denominator is Sainte-Marie. Here, in her desire to explore humanity to its fullest, she presents the most cohesive map of North America that music fans had ever seen to this point.

What to Avoid:

Sainte-Marie was prolific in the first 12 years of her career, releasing a new record almost annually. Her sophomore effort, 1965's Many a Mile, isn't by any means bad, but it's not quite as good as her debut, or the album that followed it, 1966's Little Wheel Spin and Spin. It does feature one major standout, Sainte-Marie's most covered song, "Until It's Time for You To Go." This mournful ballad is among her best songwriting, and everybody from Elvis to Streisand have taken it into their repertoire. It's gorgeous and tender, and never more so than in Sainte-Marie's no-nonsense vibrato, which somehow convincingly straddles the line between heartbroken vulnerability and steely determination.

1973's Quiet Places is unremarkable other than being her last album for her longtime label, Vanguard, while 1975's Changing Woman is so sincere it occasionally borders on excruciating.

Further Listening:

Listen to it all. Even though Sainte-Marie's career has spanned a half-century, her significant breaks mean that her discography isn't overwhelmingly large.

But if you need a few other places to start, dig into 1972's Moonshot, which is filled with all sorts of era-specific flourishes, yet also feels timeless. Her voice is an avalanche in the brilliant fuck-you rocker, "Not the Lovin' Kind," and blooms like soft petals on the flowery "I Wanna Hold Your Hand Forever" before kicking up the spurs on honky-tonk gem "My Baby Left Me." The title track itself is a thing of wonder; spacey and tense, it's a total trip on every level, tightly packed with strange arrangements.

Her greatest hits package in 1996, Up Where We Belong, is a decent survey of some of Sainte-Marie's most popular songs. It's also a wonderful opportunity to listen to her own interpretation of her Academy Award-winning title track, a completely different (and more satisfying) delivery that truly earns the triumphant swell of that infamous chorus.