Melina Matsoukas's feature directorial debut, Queen & Slim, is not a brave film.

To call something brave is to deify it, to ignore the complicated life before the death — and Queen & Slim is about many lives. It is realistic, stunning, eviscerating and expertly wrought, full of fear, blood and wrenching heartbreak, but it is also funny at points, igniting the kind of laughter that bursts through tears.

To call Queen & Slim brave is to remove ourselves from the world it's showing us, to ignore that we too are mired in this story, which leaves our heads spinning and hurting in the wake of Queen and Slim's love. To call this movie brave is to miss its point.

Queen (Jodie Turner-Smith) is a lawyer who arrives at her first date with Slim (Daniel Kaluuya) dressed in her "angelic flair": all in white, her hair in long braids like a cocoon, a safety blanket that hair sometimes is, keeping her safe from the world she knows to be against her. "She has this protective armour because she walks through life experiencing trauma on a daily basis," Matsoukas tells Exclaim! "[Queen] defends people on death row, and she's a Black woman and obviously has her own challenges. And so she's really conservative and we needed to show that." Slim, meanwhile, is a simple guy in all blue. "He's like, 'It's cold and this is my warmest jacket.' And he has his chain, which shows, you know, his proximity to God and his spirituality."

It is asking us "if Black people are appreciated in life, and how they live, or if it's in death that makes people matter," Matsoukas says "I hope [Queen & Slim] does bring empathy for people of colour. I hope that you're able to exist in their shoes, whether you're Black or not. I want all audiences to understand what it feels like when we are pulled over by police," she goes on. "When we see that siren behind us, the fear that it immediately evokes, and think about why."

Matsoukas and Lena Waithe, the film's screenwriter, are not cryptic about the film's political and social messages — it's not codified in deep metaphors and sly innuendos. Matsoukas wants the viewer to think about systemic racism while watching the film. Matsoukas wants active, diligent participation of the audience.

This is why every aspect of the film is deliberate; nothing is accidental in Matsoukas's visual vocabulary. "I come from a place where I use everything to tell you a story," she says.

This is all part of Matsoukas's excellence in storytelling — while Waithe's words paint a poetic character development, Matsoukas shows us Queen and Slim's respective growth from who they were at the beginning of the film, to who they become on their journey; how tenderness thaws their banter, eventually leading to the kind of love that destroys cities.

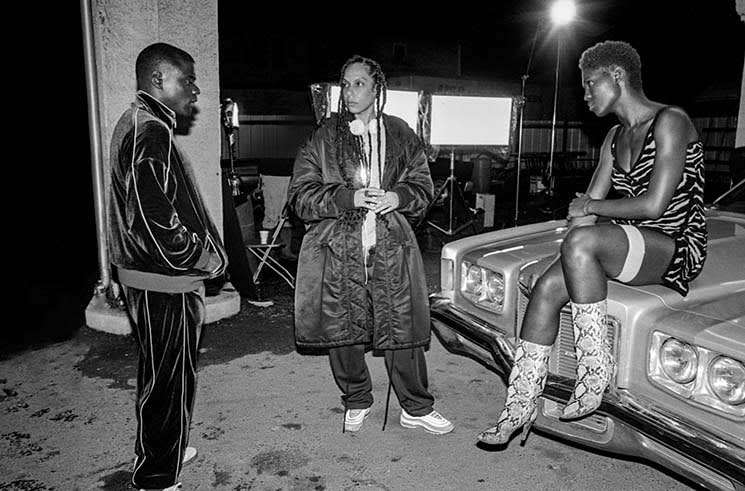

In the film's second act, the two arrive in New Orleans at Queen's uncle Earl's. Queen, covered in blood, constantly being wounded, is empowered by the sexuality of the women present. She changes into their clothes — a slip dress in yellow animal print and white snakeskin boots. "She has to un-layer, and she has to become vulnerable." She bares her arms and legs to Slim, who takes on Earl's clothes and the confidence that tragedy accrues. In his red track suit, Slim stands tall and proud and looks straight into the lens of the camera that snaps his and Queen's photo.

In the photograph that becomes an emblem of the political movement that Queen and Slim ignite — which, Matsoukas notes, climaxes alongside the two in the most striking sex scene — Queen's head is turned toward Slim. This is reminiscent of The Graduate's iconic conclusion, when the lovers flee on a bus, uncertain of their future. Queen and Slim might not know what lies ahead for them, but they are certain of one thing: their ride-or-die devotion.

Matsoukas's ability to depict the quiet between two people in love is keen. There is a scene with a white horse like out of a dream. Slim has never been on a horse before, while Queen has. His face as he climbs on, her willingness to show him how to leverage his weight on the surrounding fence, both their faces as they laugh as they run from the farmer out of frame who yells at them. It's a scene of pure joy, enveloped in shades of hazy blues and gauzy whites and emerald greens. Matsoukas delivers it in a seemingly effortless stroke. These are scenes of goodness that if self-contained would be fairy tales of a beautiful love that never ends — like when Slim gets Queen to dance with him. But of course, the film ends.

"What I do think they become a symbol of is their resilience. How they're continually able to fight back, whether it's accidental or not, and how they're also able to find hope, joy and love in the middle of this very traumatic experience," Matsoukas says.

To call something brave is to deify it, to ignore the complicated life before the death — and Queen & Slim is about many lives. It is realistic, stunning, eviscerating and expertly wrought, full of fear, blood and wrenching heartbreak, but it is also funny at points, igniting the kind of laughter that bursts through tears.

To call Queen & Slim brave is to remove ourselves from the world it's showing us, to ignore that we too are mired in this story, which leaves our heads spinning and hurting in the wake of Queen and Slim's love. To call this movie brave is to miss its point.

Queen (Jodie Turner-Smith) is a lawyer who arrives at her first date with Slim (Daniel Kaluuya) dressed in her "angelic flair": all in white, her hair in long braids like a cocoon, a safety blanket that hair sometimes is, keeping her safe from the world she knows to be against her. "She has this protective armour because she walks through life experiencing trauma on a daily basis," Matsoukas tells Exclaim! "[Queen] defends people on death row, and she's a Black woman and obviously has her own challenges. And so she's really conservative and we needed to show that." Slim, meanwhile, is a simple guy in all blue. "He's like, 'It's cold and this is my warmest jacket.' And he has his chain, which shows, you know, his proximity to God and his spirituality."

It is asking us "if Black people are appreciated in life, and how they live, or if it's in death that makes people matter," Matsoukas says "I hope [Queen & Slim] does bring empathy for people of colour. I hope that you're able to exist in their shoes, whether you're Black or not. I want all audiences to understand what it feels like when we are pulled over by police," she goes on. "When we see that siren behind us, the fear that it immediately evokes, and think about why."

Matsoukas and Lena Waithe, the film's screenwriter, are not cryptic about the film's political and social messages — it's not codified in deep metaphors and sly innuendos. Matsoukas wants the viewer to think about systemic racism while watching the film. Matsoukas wants active, diligent participation of the audience.

This is why every aspect of the film is deliberate; nothing is accidental in Matsoukas's visual vocabulary. "I come from a place where I use everything to tell you a story," she says.

This is all part of Matsoukas's excellence in storytelling — while Waithe's words paint a poetic character development, Matsoukas shows us Queen and Slim's respective growth from who they were at the beginning of the film, to who they become on their journey; how tenderness thaws their banter, eventually leading to the kind of love that destroys cities.

In the film's second act, the two arrive in New Orleans at Queen's uncle Earl's. Queen, covered in blood, constantly being wounded, is empowered by the sexuality of the women present. She changes into their clothes — a slip dress in yellow animal print and white snakeskin boots. "She has to un-layer, and she has to become vulnerable." She bares her arms and legs to Slim, who takes on Earl's clothes and the confidence that tragedy accrues. In his red track suit, Slim stands tall and proud and looks straight into the lens of the camera that snaps his and Queen's photo.

In the photograph that becomes an emblem of the political movement that Queen and Slim ignite — which, Matsoukas notes, climaxes alongside the two in the most striking sex scene — Queen's head is turned toward Slim. This is reminiscent of The Graduate's iconic conclusion, when the lovers flee on a bus, uncertain of their future. Queen and Slim might not know what lies ahead for them, but they are certain of one thing: their ride-or-die devotion.

Matsoukas's ability to depict the quiet between two people in love is keen. There is a scene with a white horse like out of a dream. Slim has never been on a horse before, while Queen has. His face as he climbs on, her willingness to show him how to leverage his weight on the surrounding fence, both their faces as they laugh as they run from the farmer out of frame who yells at them. It's a scene of pure joy, enveloped in shades of hazy blues and gauzy whites and emerald greens. Matsoukas delivers it in a seemingly effortless stroke. These are scenes of goodness that if self-contained would be fairy tales of a beautiful love that never ends — like when Slim gets Queen to dance with him. But of course, the film ends.

"What I do think they become a symbol of is their resilience. How they're continually able to fight back, whether it's accidental or not, and how they're also able to find hope, joy and love in the middle of this very traumatic experience," Matsoukas says.