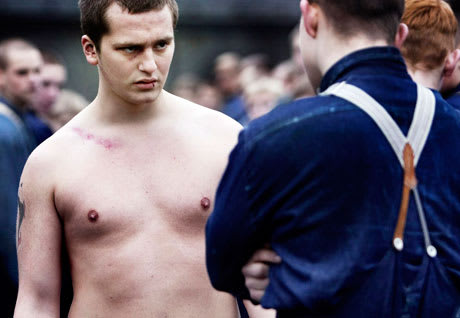

Just as the majority of haunting movies pertain to dealing with past demons, virtually all prison uprising movies work as an allegory for totalitarian rebellion, substituting the prisoners for the subjugated working class populous in an ersatz cowboy ode to male solidarity. This notion of thwarting authority for the greater good is a ubiquitous male notion or fantasy ideation, suggesting that identity comes from the assertion of self as morally righteous and superior in a phallocentric capacity. Such is the nature of the exceedingly male, yet smartly subdued and environment preoccupied Norwegian prison movie about the famed Bastoy prison, King of Devil's Island. It injects the physically imposing and self-guiding Erling (Benjamin Helstad) into a fascist teen prison enterprise of sorts where he exposes a ring of molestation and motivates the acting cabin leader, Olav (Trond Nilsson), to rebel against the terrifyingly serene and stern warden, Bestyreren (Stellan Skarsgård). It's a quiet rebellion at first, contained by the harsh winter environment and vast frozen lake surrounding the prison, while Erling tests the boundaries and slowly earns the respect of his envious and dumbfounded fellow inmates. The question of what the boys did to get to Bastoy is secondary to the bonding notion of lost identity in an environment where disobedience of the guiding rigid structure equates immediate, harsh punishment. There's a purveying, and clumsily contrived, allegory about defeating a whale, which acts as the motivator and instigator of reclaiming one's independence. This is where Devil's Island deviates from the genre, since the actual rebellion is often avoided or left off screen. Here, the climax is dedicated to the act, making the guilty pleasure and sustained optimism work against expectations. The nature of male bonding – a signifier of the genre – is repeatedly mirrored and refuted throughout the film, leaving a sense of unease where the comfort of trust and solidarity would normally thrive. Holst hasn't directly confronted cinematic expectations necessarily, but he has played with the nature of realism versus optimism in an effort to identify with the standard coming-of-age parable in relation to prison movie tropes. Included with the DVD is the short British film Bale, wherein an act of teen bullying inadvertently goes too far. And while the short film builds up well, reaching a disturbing climactic point, it ultimately plays it safe and gives in to its narrative expectations, unlike the feature film it's paired with.

(Film Movement)King of Devil's Island

Marius Holst

BY Robert BellPublished Apr 13, 2012