Gerbrand Bakker's award-winning novel, The Twin, on which Nanouk Leopold's laconic drama, It's All So Quiet is based, is a different sort of beast than the film, having a similarly pastoral setting and tone, but a plot that makes a distinct detour, maintaining the themes while modifying the presentation of sexuality.

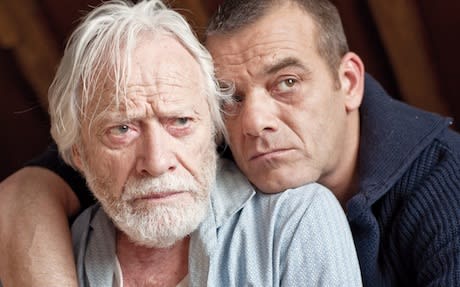

In Bakker's book, Helmer (Jeroen Willems) lives in the shadow of his dead twin. He dropped out of school ostensibly to mirror the farmer lifestyle of his brother, living in quiet isolation with his ailing father and quotidian responsibilities. Similarly, the film represses causality, hinting at resentment between Helmer and his father (Henri Garcin), hinting at a deceased brother and a sense of hardness in paternal disappointment without exploiting the concept of twin as inescapable shadow.

Instead, the love story and widow angle is dropped entirely in favour of homosexual yearning as representation of subdued identity. Rather than introducing a widow and a nephew as the book did, positing romantic rejection—the widow chose Helmer's brother over him—the film modifies the character of Henk (Martijn Lakemeier) into a passively violent, sexually confused farmhand of no relation.

Demonstrating ambivalence towards male authority figures, he responds to his new boss with simultaneous submission and petulance, unable to gain the affection he desires within the context he needs. Their collective quiet within the vacuum of expansive isolation manifests in implicit communication barriers and an eventual physical expression. It's more revelatory in action than it is sexualized, having less of a romantic context than the tense conversations between Helmer and Johan (Wim Opbrouck), a dairy truck driver that makes his romantic interests evident.

Like the novel, Leopold's contemplative, parabola of a film doesn't reveal its hand through exposition, letting the action happen before it's explained. It takes time to understand why Helmer seems to hate his father. Their banal experience and the eventual exploration of death as form of reconciliation is shown ritualistically through the changing of beds, awkward baths and a series of terse, carefully worded exchanges that suggests mutual disdain.

This is also the case with Helmer himself. His inability to verbalize or act on any of his desires demonstrates his resignation, so removed from the self that his fumbling attempts to connect are barely discernable. As framed by intimate camerawork and an earthy palette, this naturalistic, extremely subtle performance—by the late Willems—is as cautiously rendered as the subject matter.

Just as the novel took pages of seemingly mundane description to hint at a bigger human truth and allude to a theme within the obsessive observation that isolation, quiet and repetition brings, Leopold's film mostly observes characters within drab surroundings, taking everything in and leaving it to us to interpret what we see.

(Circe Films)In Bakker's book, Helmer (Jeroen Willems) lives in the shadow of his dead twin. He dropped out of school ostensibly to mirror the farmer lifestyle of his brother, living in quiet isolation with his ailing father and quotidian responsibilities. Similarly, the film represses causality, hinting at resentment between Helmer and his father (Henri Garcin), hinting at a deceased brother and a sense of hardness in paternal disappointment without exploiting the concept of twin as inescapable shadow.

Instead, the love story and widow angle is dropped entirely in favour of homosexual yearning as representation of subdued identity. Rather than introducing a widow and a nephew as the book did, positing romantic rejection—the widow chose Helmer's brother over him—the film modifies the character of Henk (Martijn Lakemeier) into a passively violent, sexually confused farmhand of no relation.

Demonstrating ambivalence towards male authority figures, he responds to his new boss with simultaneous submission and petulance, unable to gain the affection he desires within the context he needs. Their collective quiet within the vacuum of expansive isolation manifests in implicit communication barriers and an eventual physical expression. It's more revelatory in action than it is sexualized, having less of a romantic context than the tense conversations between Helmer and Johan (Wim Opbrouck), a dairy truck driver that makes his romantic interests evident.

Like the novel, Leopold's contemplative, parabola of a film doesn't reveal its hand through exposition, letting the action happen before it's explained. It takes time to understand why Helmer seems to hate his father. Their banal experience and the eventual exploration of death as form of reconciliation is shown ritualistically through the changing of beds, awkward baths and a series of terse, carefully worded exchanges that suggests mutual disdain.

This is also the case with Helmer himself. His inability to verbalize or act on any of his desires demonstrates his resignation, so removed from the self that his fumbling attempts to connect are barely discernable. As framed by intimate camerawork and an earthy palette, this naturalistic, extremely subtle performance—by the late Willems—is as cautiously rendered as the subject matter.

Just as the novel took pages of seemingly mundane description to hint at a bigger human truth and allude to a theme within the obsessive observation that isolation, quiet and repetition brings, Leopold's film mostly observes characters within drab surroundings, taking everything in and leaving it to us to interpret what we see.