Loosely based on Romeo & Juliet, Leticia Tonos Paniagua's sophomore feature, Cristo Rey, is as much about its geography as it is about the Bard's themes of passion and jealousy. The context, being set in the Dominican Republic where more than one million undocumented Haitians live and face ethnic discrimination, throws a modernist, politically conscious slant on the tragedy, accompanying the core idea of impossible connections on an island divided by racial tensions and pervading police corruption with a perpetual backbeat of Caribbean music and impromptu dance numbers.

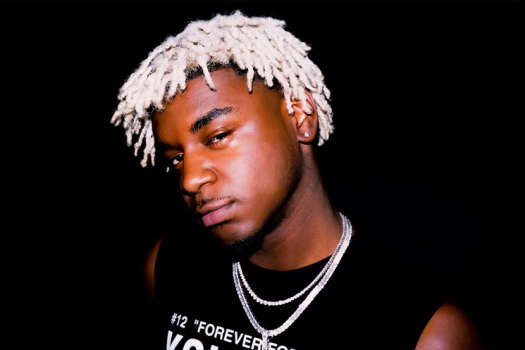

Janvier (James Saintil), a young man of mixed descent, is trapped between both worlds. He's well-intentioned, hoping to make the most of things within the Dominican despite missing his Haitian mother and wanting nothing to do with his Dominican dad and half-brother Rudy (Yasser Michelén). This is why he snaps up the opportunity to guard Jocelyn (Akari Endo), the younger sister of local drug lord El Bacá (Leonardo Vasquez), assuming it might help earn him enough money to reunite with his mother in Haiti.

During these early sequences, the inherent conflict and varying archetypes are established quite effectively. Though Tonos Panigua's vision has little stylization beyond an over-reliance on soundtrack, Janvier's honourable disposition is contrasted well with Rudy's shadier, self-serving sensibilities. Early involvement with Colonel Montilla (Jalsen Santana) establishes him as an anti-Communist tool of a dictatorial process, turning a blind eye to organized crime while harassing our protagonist enough to leave an impending sense of dread looming over the proceeding.

Where Cristo Rey stumbles is in establishing any sense of tone or narrative flexibility. The source play, once that's been adapted and performed countless times to varying effectiveness, had dramatic variance, inserting comedy and tender human drama to heighten the sense of tragedy. Here, Tonos Paniagua merely shifts the soundtrack to twee piano music and rests on overly choreographed shots of Jocelyn and Janvier standing in doorways to distinguish romantic moments from everything else, using no effective transition or aesthetic signifiers to mirror their emotional state.

It makes the development of their forbidden relationship play superficially, limited to a couple of lingering glances and a sweaty sex scene before Rudy, having been rejected by Jocelyn in the past, enacts a plan of vengeance to destroy his half-brother.

Since the socio-cultural climate was established early in the film, the abject morality demonstrated by Rudy rings of tragic learned behaviour. Beyond jealousy and a history of feeling insignificant, the climate of racial intolerance and a background of feeling implicitly superior add a sense of horrifying logic to this eventual betrayal. It's just problematic that Jocelyn's relationship with her cliché of a drug lord brother is facile and devoid of dramatic tension, as is her shallow, almost transparently irreverent and self-destructive, relationship with Janvier, making it mean very little once the inevitable conflicts spiral into fits of violence.

After the final bullets have been fired and the machetes have been dropped, all that's left to linger is a glimpse of a witty take on a globally ubiquitous tale tarnished by occasional spatially incoherent footage and out of focus shots that, as a metaphor, represent the flatness and lack of emotional awareness of the entire film quite succinctly.

(LES FILMS DE L'ASTRE)Janvier (James Saintil), a young man of mixed descent, is trapped between both worlds. He's well-intentioned, hoping to make the most of things within the Dominican despite missing his Haitian mother and wanting nothing to do with his Dominican dad and half-brother Rudy (Yasser Michelén). This is why he snaps up the opportunity to guard Jocelyn (Akari Endo), the younger sister of local drug lord El Bacá (Leonardo Vasquez), assuming it might help earn him enough money to reunite with his mother in Haiti.

During these early sequences, the inherent conflict and varying archetypes are established quite effectively. Though Tonos Panigua's vision has little stylization beyond an over-reliance on soundtrack, Janvier's honourable disposition is contrasted well with Rudy's shadier, self-serving sensibilities. Early involvement with Colonel Montilla (Jalsen Santana) establishes him as an anti-Communist tool of a dictatorial process, turning a blind eye to organized crime while harassing our protagonist enough to leave an impending sense of dread looming over the proceeding.

Where Cristo Rey stumbles is in establishing any sense of tone or narrative flexibility. The source play, once that's been adapted and performed countless times to varying effectiveness, had dramatic variance, inserting comedy and tender human drama to heighten the sense of tragedy. Here, Tonos Paniagua merely shifts the soundtrack to twee piano music and rests on overly choreographed shots of Jocelyn and Janvier standing in doorways to distinguish romantic moments from everything else, using no effective transition or aesthetic signifiers to mirror their emotional state.

It makes the development of their forbidden relationship play superficially, limited to a couple of lingering glances and a sweaty sex scene before Rudy, having been rejected by Jocelyn in the past, enacts a plan of vengeance to destroy his half-brother.

Since the socio-cultural climate was established early in the film, the abject morality demonstrated by Rudy rings of tragic learned behaviour. Beyond jealousy and a history of feeling insignificant, the climate of racial intolerance and a background of feeling implicitly superior add a sense of horrifying logic to this eventual betrayal. It's just problematic that Jocelyn's relationship with her cliché of a drug lord brother is facile and devoid of dramatic tension, as is her shallow, almost transparently irreverent and self-destructive, relationship with Janvier, making it mean very little once the inevitable conflicts spiral into fits of violence.

After the final bullets have been fired and the machetes have been dropped, all that's left to linger is a glimpse of a witty take on a globally ubiquitous tale tarnished by occasional spatially incoherent footage and out of focus shots that, as a metaphor, represent the flatness and lack of emotional awareness of the entire film quite succinctly.