"Mom, I'm finna use the van real quick. Be back in 15 minutes"

Familiar to anyone who had Kendrick Lamar's now seminal 2012 album good kid, m.A.A.d city in heavy rotation, these words are uttered by Lamar after "Compton," before slamming the door on the modest 1996 Chrysler Town and Country family minivan featured on the album's weathered Polaroid cover, theoretically denoting the official end of the album. On the deluxe version though, a couple of seconds elapse before the sound of a supersonic jet taking off signals the cue to luxuriously partake in the 3Ws, (women, weed and weather) — a stark contrast to the always-on survival mode of the rest of GKMC — via the Dr. Dre-assisted "The Recipe." While Lamar spins an homage to where he's from, the chorus captures him widening his geographical lens beyond the parochial scope of his hometown.

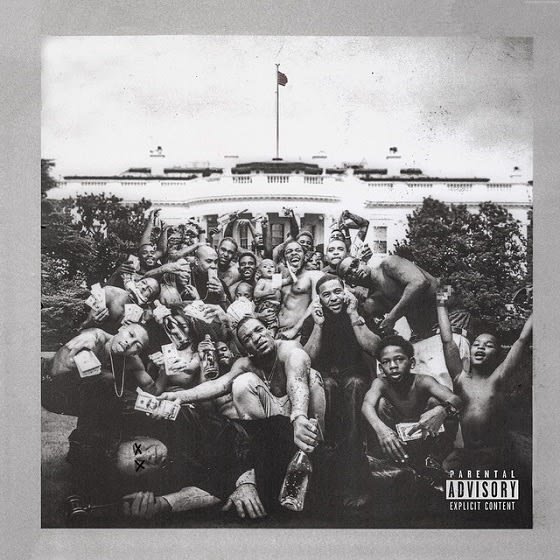

Arguably it's the nexus between planes and automobiles — the mundane and fame — in which Lamar's sophomore major label album To Pimp A Butterfly wholly exists. Throughout the album it becomes evident that despite his success, Lamar yearns to be back on his home turf, only to find it does not provide the immediate psychological and physical familiarity and comfort he craves. His reaction to this reality is lyrically and sonically exhilarating and will require multiple listens to unravel. The urge to greet the commercial and artistic triumph of a major league debut hip-hop album with a subversive stiff-arm on sophomore efforts has notable precedents in De La Soul's De La Soul Is Dead and Digable Planets' Blowout Comb, but few have been as audaciously challenging and heavily layered as Lamar's To Pimp A Butterfly, which will likely be one of 2015's most discussed, dissected and debated album releases, regardless of genre.

We got our first taste of To Pimp A Butterfly late last year through "i," which either because of its "I love myself" chorus was misinterpreted as overly self-aggrandizing or was viewed as a corny attempt to procure radio play because of its prominent recreation of the Isley Brothers "That Lady." When I spoke with Lamar backstage at Toronto's We Day concert in October last year, moments before he performed the song live for the first time, he elaborated on the song's origins. "In order to make a type of song like that, it can't be made up," Lamar said then. "You have to go through something. You have to go through depression. The people that don't really understand that song, I really can't blame them because they probably never went through anything yet and it probably hasn't settled in on them. And that's really how I've communicated on my records from day one since Kendrick Lamar EP, since Section.80; I always had some type of conflict within myself. I think we all do."

So, even while he's back at home, it's highly evident that internal battles still need to be resolved. Lamar refers to his success while others continue to struggle as "survivors guilt." The oft-invoked phrase "you can never go home again" comes to mind. So while To Pimp A Butterfly features collaborators well within the comfort zone of a traditional West coast hip-hop album on paper — from sonic forbearers like Ron Isley, as well as Snoop Dogg and Dr. Dre — given Lamar's agenda, it can't be a logical and linear continuation of good kid, m.A.A.d city. While he nods and acknowledges foundational influences, they are beginning to drift further back in the rearview mirror. Snoop briefly appears as a detached narrator on "Institutionalized," a song featuring the emotionally wrought refrain "I'm trapped inside the ghetto and I'm not proud to admit it / Institutionalized I keep runnin' back for a visit," and Dr. Dre's remotely mediated and distorted voice appears on the wary scepticism of "Wesley's Theory," prefaces Lamar's verse taking on an alternate persona (as he often does) of a predatory Uncle Sam.

An influence of greater proximity comes in the form of Flying Lotus. As the producer of album opener, "Wesley's Theory," the impact of the music produced by the sonic maverick, who emerged from the progressive Los Angeles instrumental beat scene birthed at the Low End Theory club night over the last decade, is all over the record. FlyLo himself revealed after the album's release via Twitter that Lamar crystallized his artistic direction on To Pimp A Butterfly once he had listened to a bunch of his beats. Not only that, fellow afronauts including Thundercat, Robert Glasper, Bilal and Taz Arnold (of Sa-Ra Creative Partners repute) are recruited along with TDE's Digi+Phonics crew and frequent collaborators Terrace Martin and Anna Wise to chart the new directions.

It's probably no coincidence we hear Mothership commander George Clinton's voice before we hear Lamar's at the very beginning of the album. The crew aligns with Lamar's need to draw explicitly from black musical past in the present to attempt to actualize a better future. We hear Lamar profanely channelling the spirit of the Last Poets and the Watts Prophets on "For Free? (Interlude)," mining the overtly jazzy influences he notably displayed on Section.80's "Rigamortis." Consequently, it's a necessarily circuitous journey in a search for meaning and resolution, running the emotional gamut. While the assured p-funk strut of "King Kunta," the purist rap of "Hood Politics" and the live album version of "i" retooled for maximum communal effect portray a confident Lamar at peace with his surroundings, the stark "u" features Lamar positioning himself at an alcoholic hitting rock bottom in a hotel room, guilt-ridden with self-lacerating doubt, contemplating suicide over his perceived failure to remain connected to the people in his community. And with the deaths of Michael Brown, Tamir Rice and Eric Garner looming in the background, "Alright" and its ominous sonic cousin "The Blacker The Berry" (un) convincingly presents a stoic resilience in the face of precarious mortality, extending Lamar's inner conflict to a head-on collision with present day realities of racism. It's notable Lamar does not limit this discussion to North America, with the cameo by dancehall artist Assassin on the latter track and several lyrical nods to South Africa acknowledging this reality in the diaspora.

To Pimp a Butterfly presents no easy answers to these predicaments and on album closer "Mortal Man," having raided his internal thoughts for over an hour, Lamar challenges listeners to accept him as he is despite his flaws. "As I lead this army / Make room for mistakes and depression," he says. Finally completing the reading of a poem that gradually unfurls over the album's duration, he participates in an eerie "conversation" with Tupac Shakur at the very end of the record, which is actually taken from a 1994 Swedish interview with the deceased hip-hop artist.

It's Lamar's most daring attempt on To Pimp A Butterfly to collapse space and time, and though some may feel the inclusion smacks of hubris, Lamar has often referred to Shakur once visiting him in a dream, most prominently highlighted in his 2011 "HiiiPoWeR" video, and like much of GKMC, he is unapologetically leveraging an event in his life into his music. Lamar's decision to deploy a calm demeanour in this surreal reality he has constructed is instructive, given the raspy weariness his voice takes on for much of To Pimp A Butterfly. For a moment it seems that perhaps Lamar believes he can actually go back in time and finally find peace at home, connecting with this West coast hip-hop icon, albeit in this faux-dreamlike state. It doesn't last long though. Just when Lamar suggests he may have begun to resolve his issues, Shakur disappears into the ether and we hear Lamar's frantic tone cut off in the middle of its hysterical reaction, purposefully leaving the conflict unresolved — and the destination unknown.

(Universal)Familiar to anyone who had Kendrick Lamar's now seminal 2012 album good kid, m.A.A.d city in heavy rotation, these words are uttered by Lamar after "Compton," before slamming the door on the modest 1996 Chrysler Town and Country family minivan featured on the album's weathered Polaroid cover, theoretically denoting the official end of the album. On the deluxe version though, a couple of seconds elapse before the sound of a supersonic jet taking off signals the cue to luxuriously partake in the 3Ws, (women, weed and weather) — a stark contrast to the always-on survival mode of the rest of GKMC — via the Dr. Dre-assisted "The Recipe." While Lamar spins an homage to where he's from, the chorus captures him widening his geographical lens beyond the parochial scope of his hometown.

Arguably it's the nexus between planes and automobiles — the mundane and fame — in which Lamar's sophomore major label album To Pimp A Butterfly wholly exists. Throughout the album it becomes evident that despite his success, Lamar yearns to be back on his home turf, only to find it does not provide the immediate psychological and physical familiarity and comfort he craves. His reaction to this reality is lyrically and sonically exhilarating and will require multiple listens to unravel. The urge to greet the commercial and artistic triumph of a major league debut hip-hop album with a subversive stiff-arm on sophomore efforts has notable precedents in De La Soul's De La Soul Is Dead and Digable Planets' Blowout Comb, but few have been as audaciously challenging and heavily layered as Lamar's To Pimp A Butterfly, which will likely be one of 2015's most discussed, dissected and debated album releases, regardless of genre.

We got our first taste of To Pimp A Butterfly late last year through "i," which either because of its "I love myself" chorus was misinterpreted as overly self-aggrandizing or was viewed as a corny attempt to procure radio play because of its prominent recreation of the Isley Brothers "That Lady." When I spoke with Lamar backstage at Toronto's We Day concert in October last year, moments before he performed the song live for the first time, he elaborated on the song's origins. "In order to make a type of song like that, it can't be made up," Lamar said then. "You have to go through something. You have to go through depression. The people that don't really understand that song, I really can't blame them because they probably never went through anything yet and it probably hasn't settled in on them. And that's really how I've communicated on my records from day one since Kendrick Lamar EP, since Section.80; I always had some type of conflict within myself. I think we all do."

So, even while he's back at home, it's highly evident that internal battles still need to be resolved. Lamar refers to his success while others continue to struggle as "survivors guilt." The oft-invoked phrase "you can never go home again" comes to mind. So while To Pimp A Butterfly features collaborators well within the comfort zone of a traditional West coast hip-hop album on paper — from sonic forbearers like Ron Isley, as well as Snoop Dogg and Dr. Dre — given Lamar's agenda, it can't be a logical and linear continuation of good kid, m.A.A.d city. While he nods and acknowledges foundational influences, they are beginning to drift further back in the rearview mirror. Snoop briefly appears as a detached narrator on "Institutionalized," a song featuring the emotionally wrought refrain "I'm trapped inside the ghetto and I'm not proud to admit it / Institutionalized I keep runnin' back for a visit," and Dr. Dre's remotely mediated and distorted voice appears on the wary scepticism of "Wesley's Theory," prefaces Lamar's verse taking on an alternate persona (as he often does) of a predatory Uncle Sam.

An influence of greater proximity comes in the form of Flying Lotus. As the producer of album opener, "Wesley's Theory," the impact of the music produced by the sonic maverick, who emerged from the progressive Los Angeles instrumental beat scene birthed at the Low End Theory club night over the last decade, is all over the record. FlyLo himself revealed after the album's release via Twitter that Lamar crystallized his artistic direction on To Pimp A Butterfly once he had listened to a bunch of his beats. Not only that, fellow afronauts including Thundercat, Robert Glasper, Bilal and Taz Arnold (of Sa-Ra Creative Partners repute) are recruited along with TDE's Digi+Phonics crew and frequent collaborators Terrace Martin and Anna Wise to chart the new directions.

It's probably no coincidence we hear Mothership commander George Clinton's voice before we hear Lamar's at the very beginning of the album. The crew aligns with Lamar's need to draw explicitly from black musical past in the present to attempt to actualize a better future. We hear Lamar profanely channelling the spirit of the Last Poets and the Watts Prophets on "For Free? (Interlude)," mining the overtly jazzy influences he notably displayed on Section.80's "Rigamortis." Consequently, it's a necessarily circuitous journey in a search for meaning and resolution, running the emotional gamut. While the assured p-funk strut of "King Kunta," the purist rap of "Hood Politics" and the live album version of "i" retooled for maximum communal effect portray a confident Lamar at peace with his surroundings, the stark "u" features Lamar positioning himself at an alcoholic hitting rock bottom in a hotel room, guilt-ridden with self-lacerating doubt, contemplating suicide over his perceived failure to remain connected to the people in his community. And with the deaths of Michael Brown, Tamir Rice and Eric Garner looming in the background, "Alright" and its ominous sonic cousin "The Blacker The Berry" (un) convincingly presents a stoic resilience in the face of precarious mortality, extending Lamar's inner conflict to a head-on collision with present day realities of racism. It's notable Lamar does not limit this discussion to North America, with the cameo by dancehall artist Assassin on the latter track and several lyrical nods to South Africa acknowledging this reality in the diaspora.

To Pimp a Butterfly presents no easy answers to these predicaments and on album closer "Mortal Man," having raided his internal thoughts for over an hour, Lamar challenges listeners to accept him as he is despite his flaws. "As I lead this army / Make room for mistakes and depression," he says. Finally completing the reading of a poem that gradually unfurls over the album's duration, he participates in an eerie "conversation" with Tupac Shakur at the very end of the record, which is actually taken from a 1994 Swedish interview with the deceased hip-hop artist.

It's Lamar's most daring attempt on To Pimp A Butterfly to collapse space and time, and though some may feel the inclusion smacks of hubris, Lamar has often referred to Shakur once visiting him in a dream, most prominently highlighted in his 2011 "HiiiPoWeR" video, and like much of GKMC, he is unapologetically leveraging an event in his life into his music. Lamar's decision to deploy a calm demeanour in this surreal reality he has constructed is instructive, given the raspy weariness his voice takes on for much of To Pimp A Butterfly. For a moment it seems that perhaps Lamar believes he can actually go back in time and finally find peace at home, connecting with this West coast hip-hop icon, albeit in this faux-dreamlike state. It doesn't last long though. Just when Lamar suggests he may have begun to resolve his issues, Shakur disappears into the ether and we hear Lamar's frantic tone cut off in the middle of its hysterical reaction, purposefully leaving the conflict unresolved — and the destination unknown.