Eric Church is one of the most important musicians working today. But have you ever even heard him? Most urban music fans haven't. This should change.

Though we pay attention to Kanye West (even if we don't follow hip-hop that closely) and we cheer on Beyoncé (even if we haven't bought a pop record by anyone else for years), why is it that we have tended to ignore the other mainstream artist who has had a comparable effect on his genre? If it's simply the fact that many of us don't like mainstream country music then, good news! He doesn't make mainstream country music. Not really.

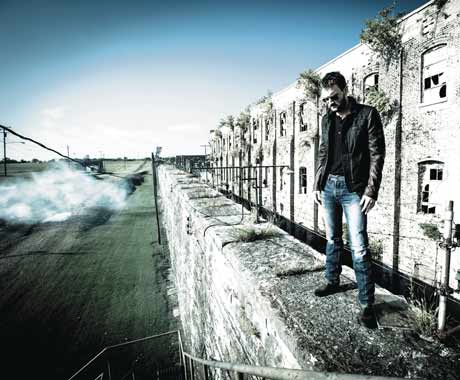

A bona fide superstar, Church has sold over three million records, and his 2011 album Chief went number one on the charts. Not the country charts: the Billboard charts. Featuring the smash hit "Springsteen," a summer-defining ode to the intersection of music, nostalgia, and identity, Chief was also something of a wake-up call for many in the music industry. Here was a Nashville-based country singer who hit it way out of the park with a song about his love for a rock-god Democrat from New Jersey. And, even more confounding, Chief was chock-full of arrangements that owed more to '70s rock than to the Grand Ole Opry.

Eric Church loves big crunchy guitars and pounding drums. He leans toward recalcitrance, and he admires iconoclasts. He loves his craft and is an alarmingly prolific songwriter. (He claims to have written 121 songs for The Outsiders, just as a holy shit example.) What he doesn't much like are genre distinctions. Told for ages that he was too rock'n'roll for country music, he kept his head down and wrote and played, certain that there was an audience for what he was trying to do. Story goes he used to send his guitarist out to play Pantera at the audience to chase out the old fogeys; he figured anyone that remained was probably going to appreciate what he was up to.

Early on, he connected with producer Jay Joyce ("We wouldn't be here without Jay," he tells me), and the sound began to form: not exactly Southern rock, not exactly heavy metal, not quite honky-tonk, not really alt-rock, and, most interestingly of all, not alt-country either. Make no mistake, Eric Church is closer to George Strait than he is to Jay Farrar. But, he's also a lot closer to Led Zeppelin than to Shania Twain. It's a fascinating musical concoction, and it has been damn exciting to watch it develop. On his latest (and best) record, The Outsiders, Church amplifies this Nashville-via-Sabbath approach to astonishing effect. The title track, for instance, sounds like very little (perhaps nothing at all) that has ever been on a mainstream country record. Culminating in a proggy section that jumps time signatures and pushes well into Metallica territory, you can see why a lot of the Stetson-and-cowboy-boot set in Music City is a bit unsure of what to do with this guy in aviator shades and trucker cap.

Guys, I have a suggestion: Turn it up. Loud.

The word "outsider" conjures up the "outlaw country" subgenre of the '70s (Willie Nelson, Merle Haggard, Waylon Jennings, Jerry Jeff Walker, and others) which was as much about marking territory outside mainstream country as it was about how Nashville didn't approve of their style. Is this how you see yourself? Or how Nashville sees you?

The term "outlaw" comes off as… You know, I hate that. It's their term. I get that a lot. [laughs] I hate that we continue to regurgitate that term to describe… I don't know what we are. I know that we've had a different journey. We've had a different path. There have been many times, earlier in our career, when our kind of music did not fit in. I remember when we first started, with our Sinners Like Me album, believe it or not, it was a time in country music that women dominated. If you weren't making country music for a 40- or 45-year-old "soccer mom," you weren't going to get played. And we didn't have that kind of music! So, it's always been a bit of an arm's length thing for us. Songs like "Smoke a Little Smoke," "Homeboy," "Outsiders"? Those songs did not fit exactly what the format is, or what the format says I should do. But, I've never really focused on that. I don't know what you'd call that. But, I never really focused on those things.

Because we came up in bars and clubs, we identified real early on who our fan base was. I looked them in the eye, you know, at 11 o'clock at night at a little rock club. And I've always tried to make the music for them. For that front row; not "Music Row." I think that sums up our whole career. That's been the crux of everything we've done. When we write a song, or record a song, [we ask ourselves]: How is the crowd going to respond to it? Who are we talking to? And at times that has absolutely not been what Nashville was doing, or was interested in doing. But, I've never really focused on that part of it. I've just continued to make the music for the people.

In the prelude to "Devil Devil" you recite a lengthy poem about your love-hate relationship with Nashville. I bet that many of our readers at Exclaim! would say that they love country music, but hate Nashville radio country. Does that distinction ring true for you?

Well, there's a couple things there. One thing that's always intrigued me about Nashville is that the difference between the guy or girl standing on the corner with two dollars and a hat playing a guitar in front of some place on Broadway, and a guy or girl playing for 10,000 people at the arena is very, very, very small. I've always been intrigued by the way Nashville can make one person's dreams completely come true, and for this other person completely crush them. And it doesn't ever seem fair.

I know so many people that are so talented that I've met along my journey that are the best writers or singers or players and for whatever reason — they didn't get the breaks or they didn't play by a certain set of rules –Nashville crushed them. And the other ones are, you know, superstars.

The dichotomy there between the two sides has always intrigued me. It's almost like Nashville is — well that's how I painted it, as the "devil's bride" in that poem, basically — showing that she can be really cruel, and at the same time she can make all of your dreams come true. I don't know why that is. I know some people don't conform the way others do. I know a lot of it is political. And, I know a lot of it is just dumb luck. But when you put all of that stuff together it makes for an incredibly interesting town to live and work in. Everybody here, eight out of ten people, are either in music or want to be in music. Every time you run into somebody, they all have dreams. And those dreams are either going to be realized or get crushed. There is no grey area with this town.

Country radio has been frustrating for the past several years. Big hit songs mostly sung by men about partying, screwing. frat-party anthem type stuff. Is your work consciously opposed to these clichés?

The biggest thing with music — of all kinds — is that if it's authentic to you, I've got no problem with it. We've always been able to make the music that's authentic to us. And we've not worried that it was "country" or was not "country" or was "rock" or was not "rock". Or was whatever. We've just made the music; we just followed the music there. With everything [in country music] from when we started out to where it is now, I'm fine with it. As long as it's authentic.

I think that the problem that everybody gets into — and this isn't just country music; to me, this is all popular music — is that we play follow the leader. When something works, ten other people try it. And then a hundred people try it. And when you're doing that, what you're doing is you're chasing success. You're not chasing who you are artistically. I think that when you do that, regardless of the musical genre, you really pigeonholing the music. You're really pigeonholing the creativity. And that? I have a problem with that.

If people are in this industry for inauthentic reasons — I want to be famous, or I want to have a number one or whatever — that's when we get into trouble. Those people aren't following a creative vision. But I think we do music a service if we're really paying attention to that creative impulse and following it.

On your last record you sang about needing a "Country Music Jesus" to come and save us all. "We need a second coming worse than bad." Is this what you were getting at?

No! Actually that was tongue-in-cheek! I read a review around the time I was writing songs for the Chief record. And I was involved in the review. The guy was hitting me pretty hard, saying I was "too rock'n'roll" and everything. And then at the end of the article the guy put in there that "what this format needs is a country music Jesus to come and save our soul." And I just loved the tongue-in-cheek of that. That was much less serious than I think some people take it. That was just to poke fun.

To me, people just need to do what they do, musically. And we need to quit trying to put it in a genre, or a sub-genre, saying this is this and this is that. I think in this day and age if you're a 20-year-old you're not listening to music based on what genre it is or what stations it's on. You're consuming an amazing amount of music. Every type. Whether it be on your mobile device or your computer or on satellite radio or terrestrial radio, every way. And that has changed the game of music. The lines between formats and genres are so blurred now that we all live in this shared space. I believe we should all be allowed to do whatever we want in that shared space. I know that for the sake of putting it in places we have to call it things. I get that. We can't just call it "music." But, the lines are way more blurry now. And I, for one, am fine with that. That allows for more creativity, and that allows for more diversity. More room for us to explore.

Isn't that kind of utopian? We don't have genres just to delineate what music sounds like, but also to reflect the identity of the artist or, in many cases, the listener. The stereotypical country music fan is white, working class, rural, and Republican. There's a tribalism about genre that holds meaning.

I think that historically that has been true. Yes. Historically you're correct. But, and I don't know where that age is — maybe it's 20, maybe it's 24, maybe it's 26 — but wherever this next generation that's coming up is [it's different]. From the shows that I've played, from playing the Orion Festival in front of metalheads [who were there] for Metallica, as the only country act, to playing Lollapalooza, to opening for George Straight on his farewell tour, to the week before doing a tribute show for Gregg Allman… You know, I think that it's a more shared space now, and especially for the younger generation. They're not drawing the same lines that maybe somebody my age, I'm 36, up to 56 would. But, we just came up a bit differently. We consumed music differently. But, in this day and time, think about when you are watching television at night and some song comes up and you just get on your iPhone or whatever you got, and you buy it right there, not knowing what genre it fits in. You just liked the sound of it. Then that song leads you to this, or that, or the other. And that's only going to expand. With the way televisions are, with the way we're talking about marketing music over the next ten years, that's where we're going. Music is moving much farther away from the way we've subdivided formats.

I think the interesting thing is that there still are a bunch of stigmas about what this is or what that is. But I think the stigmas go away in the next ten years, if they're not already going away now. I don't know what that means, I really don't.

People ask me all the time: "Do you worry about the identity of country music?" And here's what I think. Country music still comes back to songwriting. It's the home of the singer-songwriter. If you come down to Nashville, the one identity it has is that it's a songwriting town. That's different from New York, different from L.A., different from Chicago or New Orleans. It is a songwriting town. And as long as we're being true to the craft, to songwriting, to great songs, that will remain Nashville's identity. As long as we're paying attention to that, the music can evolve to where it needs to evolve.

Getting back to the genre thing one more time because this is a soap box thing for me [laughs]: Personally, man, I am looking forward [to the end of "genres"]. A lot of it has to do with who I hang out with, who my friends are. I hang out with people from all different "genres," and we all find such commonalities. (I say "genre" with quotes around it now.) But, wherever they come from musically, we share a lot of the same influences. I mean, I have an incredible reverence for country music. I could sit down with a guitar and do about anything any traditional purist wanted me to do. But I could also do that with other kinds of music. I could do it with folk, I could do it with rock. Maybe even some in metal! [laughs] That's how I grew up. I grew up consuming different kinds of music, and all that comes out when we make our records.

Maybe it's because we're exactly the same age, but I really feel like Outsiders is quoting from music I grew up with, too. That late bridge on the title track is right out of '80s metal, and the progression on "Damn Rock and Roll" quotes "Highway to Hell."

Yeah, it is! It definitely is, yeah. [laughs]

And the guitar solo on "Cold One" sounds like it could be Tom Morello from Rage Against the Machine.

Yeah, it's Rage. It's Rage meets the Band, or Little Feat. More the Band. Me, I'm a big Levon Helm and the Band fan, and I just hear that, man. It's the slinkiness of the drums, and when the stabs come in it's like a totally different element, too. A totally different influence. But, yeah. There's a lot of that [on the record]. And when people talk about "Well, where does this fit?" that's where I have to stand up and say "You know, I have no idea. It's authentic to me." And, yeah, maybe The Outsiders is the hardest rocking thing ever on country radio, but I grew up on a lot of rock'n'roll, so for me it's not hard to go there. It's a big part of my influence.

You mentioned Gregg Allman [of the Allman Brothers Band] earlier. I hear that Southern rock school of hard country-blues, and then there's… metal. It seems like The Outsiders has found a route to drive right between them, pulling from both sides.

I think it starts in one and then it goes to the other. The way "The Outsiders" starts, I mean that Telecaster could have been anything Waylon Jennings did. So, you start there. And the great thing about the way we work in the studio is, because we have a pretty creative environment, we didn't have a plan for where that [song] was headed. As we were cutting that song, and we got to what I thought was the end of the song, my producer [Jay Joyce] started that guitar riff that sounds like a... like a dying elephant! [laughs] And when he played that guitar riff it really changed what the next part of the song was, which is a minute-and-a-half of this progression where the music changes three times, the time signature changes three, four times. It just went on its own journey. And I love that because there's a part of that that sounds like Black Sabbath, you know? There's a part of that that sounds like it could go metal. Especially the last section.

Oh, yeah.

I just love that when it was done and we listened back to it, 99 percent of the people that heard it just went: "I don't know what the hell that is! I love it." And that's what you want! You want 'em just calling it "good." You don't care where they put it.

Though we pay attention to Kanye West (even if we don't follow hip-hop that closely) and we cheer on Beyoncé (even if we haven't bought a pop record by anyone else for years), why is it that we have tended to ignore the other mainstream artist who has had a comparable effect on his genre? If it's simply the fact that many of us don't like mainstream country music then, good news! He doesn't make mainstream country music. Not really.

A bona fide superstar, Church has sold over three million records, and his 2011 album Chief went number one on the charts. Not the country charts: the Billboard charts. Featuring the smash hit "Springsteen," a summer-defining ode to the intersection of music, nostalgia, and identity, Chief was also something of a wake-up call for many in the music industry. Here was a Nashville-based country singer who hit it way out of the park with a song about his love for a rock-god Democrat from New Jersey. And, even more confounding, Chief was chock-full of arrangements that owed more to '70s rock than to the Grand Ole Opry.

Eric Church loves big crunchy guitars and pounding drums. He leans toward recalcitrance, and he admires iconoclasts. He loves his craft and is an alarmingly prolific songwriter. (He claims to have written 121 songs for The Outsiders, just as a holy shit example.) What he doesn't much like are genre distinctions. Told for ages that he was too rock'n'roll for country music, he kept his head down and wrote and played, certain that there was an audience for what he was trying to do. Story goes he used to send his guitarist out to play Pantera at the audience to chase out the old fogeys; he figured anyone that remained was probably going to appreciate what he was up to.

Early on, he connected with producer Jay Joyce ("We wouldn't be here without Jay," he tells me), and the sound began to form: not exactly Southern rock, not exactly heavy metal, not quite honky-tonk, not really alt-rock, and, most interestingly of all, not alt-country either. Make no mistake, Eric Church is closer to George Strait than he is to Jay Farrar. But, he's also a lot closer to Led Zeppelin than to Shania Twain. It's a fascinating musical concoction, and it has been damn exciting to watch it develop. On his latest (and best) record, The Outsiders, Church amplifies this Nashville-via-Sabbath approach to astonishing effect. The title track, for instance, sounds like very little (perhaps nothing at all) that has ever been on a mainstream country record. Culminating in a proggy section that jumps time signatures and pushes well into Metallica territory, you can see why a lot of the Stetson-and-cowboy-boot set in Music City is a bit unsure of what to do with this guy in aviator shades and trucker cap.

Guys, I have a suggestion: Turn it up. Loud.

The word "outsider" conjures up the "outlaw country" subgenre of the '70s (Willie Nelson, Merle Haggard, Waylon Jennings, Jerry Jeff Walker, and others) which was as much about marking territory outside mainstream country as it was about how Nashville didn't approve of their style. Is this how you see yourself? Or how Nashville sees you?

The term "outlaw" comes off as… You know, I hate that. It's their term. I get that a lot. [laughs] I hate that we continue to regurgitate that term to describe… I don't know what we are. I know that we've had a different journey. We've had a different path. There have been many times, earlier in our career, when our kind of music did not fit in. I remember when we first started, with our Sinners Like Me album, believe it or not, it was a time in country music that women dominated. If you weren't making country music for a 40- or 45-year-old "soccer mom," you weren't going to get played. And we didn't have that kind of music! So, it's always been a bit of an arm's length thing for us. Songs like "Smoke a Little Smoke," "Homeboy," "Outsiders"? Those songs did not fit exactly what the format is, or what the format says I should do. But, I've never really focused on that. I don't know what you'd call that. But, I never really focused on those things.

Because we came up in bars and clubs, we identified real early on who our fan base was. I looked them in the eye, you know, at 11 o'clock at night at a little rock club. And I've always tried to make the music for them. For that front row; not "Music Row." I think that sums up our whole career. That's been the crux of everything we've done. When we write a song, or record a song, [we ask ourselves]: How is the crowd going to respond to it? Who are we talking to? And at times that has absolutely not been what Nashville was doing, or was interested in doing. But, I've never really focused on that part of it. I've just continued to make the music for the people.

In the prelude to "Devil Devil" you recite a lengthy poem about your love-hate relationship with Nashville. I bet that many of our readers at Exclaim! would say that they love country music, but hate Nashville radio country. Does that distinction ring true for you?

Well, there's a couple things there. One thing that's always intrigued me about Nashville is that the difference between the guy or girl standing on the corner with two dollars and a hat playing a guitar in front of some place on Broadway, and a guy or girl playing for 10,000 people at the arena is very, very, very small. I've always been intrigued by the way Nashville can make one person's dreams completely come true, and for this other person completely crush them. And it doesn't ever seem fair.

I know so many people that are so talented that I've met along my journey that are the best writers or singers or players and for whatever reason — they didn't get the breaks or they didn't play by a certain set of rules –Nashville crushed them. And the other ones are, you know, superstars.

The dichotomy there between the two sides has always intrigued me. It's almost like Nashville is — well that's how I painted it, as the "devil's bride" in that poem, basically — showing that she can be really cruel, and at the same time she can make all of your dreams come true. I don't know why that is. I know some people don't conform the way others do. I know a lot of it is political. And, I know a lot of it is just dumb luck. But when you put all of that stuff together it makes for an incredibly interesting town to live and work in. Everybody here, eight out of ten people, are either in music or want to be in music. Every time you run into somebody, they all have dreams. And those dreams are either going to be realized or get crushed. There is no grey area with this town.

Country radio has been frustrating for the past several years. Big hit songs mostly sung by men about partying, screwing. frat-party anthem type stuff. Is your work consciously opposed to these clichés?

The biggest thing with music — of all kinds — is that if it's authentic to you, I've got no problem with it. We've always been able to make the music that's authentic to us. And we've not worried that it was "country" or was not "country" or was "rock" or was not "rock". Or was whatever. We've just made the music; we just followed the music there. With everything [in country music] from when we started out to where it is now, I'm fine with it. As long as it's authentic.

I think that the problem that everybody gets into — and this isn't just country music; to me, this is all popular music — is that we play follow the leader. When something works, ten other people try it. And then a hundred people try it. And when you're doing that, what you're doing is you're chasing success. You're not chasing who you are artistically. I think that when you do that, regardless of the musical genre, you really pigeonholing the music. You're really pigeonholing the creativity. And that? I have a problem with that.

If people are in this industry for inauthentic reasons — I want to be famous, or I want to have a number one or whatever — that's when we get into trouble. Those people aren't following a creative vision. But I think we do music a service if we're really paying attention to that creative impulse and following it.

On your last record you sang about needing a "Country Music Jesus" to come and save us all. "We need a second coming worse than bad." Is this what you were getting at?

No! Actually that was tongue-in-cheek! I read a review around the time I was writing songs for the Chief record. And I was involved in the review. The guy was hitting me pretty hard, saying I was "too rock'n'roll" and everything. And then at the end of the article the guy put in there that "what this format needs is a country music Jesus to come and save our soul." And I just loved the tongue-in-cheek of that. That was much less serious than I think some people take it. That was just to poke fun.

To me, people just need to do what they do, musically. And we need to quit trying to put it in a genre, or a sub-genre, saying this is this and this is that. I think in this day and age if you're a 20-year-old you're not listening to music based on what genre it is or what stations it's on. You're consuming an amazing amount of music. Every type. Whether it be on your mobile device or your computer or on satellite radio or terrestrial radio, every way. And that has changed the game of music. The lines between formats and genres are so blurred now that we all live in this shared space. I believe we should all be allowed to do whatever we want in that shared space. I know that for the sake of putting it in places we have to call it things. I get that. We can't just call it "music." But, the lines are way more blurry now. And I, for one, am fine with that. That allows for more creativity, and that allows for more diversity. More room for us to explore.

Isn't that kind of utopian? We don't have genres just to delineate what music sounds like, but also to reflect the identity of the artist or, in many cases, the listener. The stereotypical country music fan is white, working class, rural, and Republican. There's a tribalism about genre that holds meaning.

I think that historically that has been true. Yes. Historically you're correct. But, and I don't know where that age is — maybe it's 20, maybe it's 24, maybe it's 26 — but wherever this next generation that's coming up is [it's different]. From the shows that I've played, from playing the Orion Festival in front of metalheads [who were there] for Metallica, as the only country act, to playing Lollapalooza, to opening for George Straight on his farewell tour, to the week before doing a tribute show for Gregg Allman… You know, I think that it's a more shared space now, and especially for the younger generation. They're not drawing the same lines that maybe somebody my age, I'm 36, up to 56 would. But, we just came up a bit differently. We consumed music differently. But, in this day and time, think about when you are watching television at night and some song comes up and you just get on your iPhone or whatever you got, and you buy it right there, not knowing what genre it fits in. You just liked the sound of it. Then that song leads you to this, or that, or the other. And that's only going to expand. With the way televisions are, with the way we're talking about marketing music over the next ten years, that's where we're going. Music is moving much farther away from the way we've subdivided formats.

I think the interesting thing is that there still are a bunch of stigmas about what this is or what that is. But I think the stigmas go away in the next ten years, if they're not already going away now. I don't know what that means, I really don't.

People ask me all the time: "Do you worry about the identity of country music?" And here's what I think. Country music still comes back to songwriting. It's the home of the singer-songwriter. If you come down to Nashville, the one identity it has is that it's a songwriting town. That's different from New York, different from L.A., different from Chicago or New Orleans. It is a songwriting town. And as long as we're being true to the craft, to songwriting, to great songs, that will remain Nashville's identity. As long as we're paying attention to that, the music can evolve to where it needs to evolve.

Getting back to the genre thing one more time because this is a soap box thing for me [laughs]: Personally, man, I am looking forward [to the end of "genres"]. A lot of it has to do with who I hang out with, who my friends are. I hang out with people from all different "genres," and we all find such commonalities. (I say "genre" with quotes around it now.) But, wherever they come from musically, we share a lot of the same influences. I mean, I have an incredible reverence for country music. I could sit down with a guitar and do about anything any traditional purist wanted me to do. But I could also do that with other kinds of music. I could do it with folk, I could do it with rock. Maybe even some in metal! [laughs] That's how I grew up. I grew up consuming different kinds of music, and all that comes out when we make our records.

Maybe it's because we're exactly the same age, but I really feel like Outsiders is quoting from music I grew up with, too. That late bridge on the title track is right out of '80s metal, and the progression on "Damn Rock and Roll" quotes "Highway to Hell."

Yeah, it is! It definitely is, yeah. [laughs]

And the guitar solo on "Cold One" sounds like it could be Tom Morello from Rage Against the Machine.

Yeah, it's Rage. It's Rage meets the Band, or Little Feat. More the Band. Me, I'm a big Levon Helm and the Band fan, and I just hear that, man. It's the slinkiness of the drums, and when the stabs come in it's like a totally different element, too. A totally different influence. But, yeah. There's a lot of that [on the record]. And when people talk about "Well, where does this fit?" that's where I have to stand up and say "You know, I have no idea. It's authentic to me." And, yeah, maybe The Outsiders is the hardest rocking thing ever on country radio, but I grew up on a lot of rock'n'roll, so for me it's not hard to go there. It's a big part of my influence.

You mentioned Gregg Allman [of the Allman Brothers Band] earlier. I hear that Southern rock school of hard country-blues, and then there's… metal. It seems like The Outsiders has found a route to drive right between them, pulling from both sides.

I think it starts in one and then it goes to the other. The way "The Outsiders" starts, I mean that Telecaster could have been anything Waylon Jennings did. So, you start there. And the great thing about the way we work in the studio is, because we have a pretty creative environment, we didn't have a plan for where that [song] was headed. As we were cutting that song, and we got to what I thought was the end of the song, my producer [Jay Joyce] started that guitar riff that sounds like a... like a dying elephant! [laughs] And when he played that guitar riff it really changed what the next part of the song was, which is a minute-and-a-half of this progression where the music changes three times, the time signature changes three, four times. It just went on its own journey. And I love that because there's a part of that that sounds like Black Sabbath, you know? There's a part of that that sounds like it could go metal. Especially the last section.

Oh, yeah.

I just love that when it was done and we listened back to it, 99 percent of the people that heard it just went: "I don't know what the hell that is! I love it." And that's what you want! You want 'em just calling it "good." You don't care where they put it.