From religious martyrs to reality TV, from rubbernecking at accident sites to building celebrity death shrines, our attraction to other peoples suffering permeates pop culture. The vicarious thrills we derive from disturbed art are always enhanced by a twist of true tragedy, which is one reason why dying is such a lucrative career move. Myth never fails to push posthumous units, and sometimes it paves an expressway to canonization.

The old Christian chestnut "he died for our sins arises with surprising ease in profiles of dead musicians, and Ian Curtis, Kurt Cobain, Richey Edwards and Tupac Shakur left behind no shortage of birds eye poetry, stained by Biblical brutality, to fuel their ascendance as icons. But this brand of reverence often breeds misconceptions and glorifies weakness, which does a disservice to the artists memory, and perhaps even perpetuates a tragic cycle. Doom-laden art is authenticated by an artists demise, but quixotic quests to keep it real can actually hasten their downfall. For these four men, that meant either wallowing in the wake of their own unfortunate idols, overexposing their suffering (attracting both like-minded fans and an invasive media), or striving to live up to the ideals of street credibility put forth by punk rock and hip-hop. These are complex characters blessed with talent, but cursed with irreconcilable dualities and other inner turmoil that stymied their rebellious nature and drove them into the ground. And the more their flaws are trivialized, glamorised or confused by myth, the more sad souls may follow them, taking strange comfort in precedent.

The past is now part of my future

"Watched from the wings as the scenes were replaying, We saw ourselves now as we never had seen Portrayal of the trauma and degeneration The sorrows we suffered and never were free.

From "Decades by Joy Division

In life, Ian Curtis was the leader of a mildly successful post-punk band, as well as a husband, father, boyfriend and job centre employee. In death, his band Joy Division has become legendary, perhaps never more popular and influential than they are now, due in part to mounting depictions of its singers suffering, cast in shadows of classic mythology.

Though the media has occasionally treated Curtis to such epithets as "saddo who couldnt hack it, the rumour that he may have "died for you began to emerge in his obituaries. Beneath the hype, and strewn across Curtiss lyrics, are the more humdrum motivations for his suicide in May 1980: guilt over the break-up of his family, and depression exacerbated by crude epilepsy meds. Although his ambition may have been stunted by his illnesses, and what biographer Lindsay Reade calls a "fear of the next level his death occurred on the eve of what would have been Joy Divisions first North American tour it could be argued that the appeal of posterity was never far from his mind.

In her 1995 memoir, Touching From a Distance, Deborah Curtis wrote about her late husbands predilection for artists who died young, and his expressed desire to follow suit. This revelation arises in Michael Winterbottoms 2002 film, 24 Hour Party People, in which Curtis is part of the larger story of Manchesters Factory Records and its founder, the late Tony Wilson. One scene finds Curtis disagreeing with Wilsons opinion that artists often produce their best work in old age. Wilson mentions W.B. Yeats, an unfamiliar name to Curtis, who says he would have heard of him if hed died by 25. In a later scene, he walks past a Doors poster in his house, an allusion to his idolatry of Jim Morrison.

"Perhaps he did crave the romantic mythology, says Reade, who was married to Wilson during Factorys early days, as portrayed in 24 Hour Party People. Torn Apart, a chronicle of Curtiss life in and out of the band, co-authored by Reade and Mick Middles, also addresses allegations of the singers clairvoyance and mediumship, traits historically ascribed to epileptics (as is demonic possession, though no one has yet to make that claim). "Something was going on with him that people were unaware of, she says. Next to Morrisons death by decadence in a Parisian bathtub, Curtiss hanging in his humble Macclesfield kitchen is decidedly devoid of glamour, yet its hit the silver screen twice, most recently in Control, a conventional Curtis biopic rendered in gorgeous black and white by onetime Joy Division photographer Anton Corbijn. Film audiences have also been privy to Curtiss "fits and the "dead fly dance that appears to simulate them. Though his affliction was kept secret, contemporary critics remarked on the resemblance between Curtiss trademark moves and epileptic seizures, as did Deborah, who witnessed both firsthand. Its even been suggested that he purposely triggered his on-stage seizures, which is hard to reconcile with the horrified feelings he expressed on these few occasions. But in an Under Review documentary that speculates on this subject, a clip from one of Curtiss few recorded interviews is played: "Instead of just singing about something, you can actually show it as well. Theres no need to just simulate when you can put it over the way it is. Considering the relative scarcity of documentation of Curtiss life and work, theres a surprising abundance of strangely telling detail surrounding his death: the last movie he watched (Werner Herzogs Stroszek, about a disastrous American venture by a band of European misfits), the last record he listened to (Iggy Pops The Idiot), the book his girlfriend was reading at the time (also The Idiot, by Dostoyevsky, about a saintly epileptic), the song his wife dreamt about the morning he died ("The End, by the Doors) and the sleeve design of Closer, depicting a dead Christ figure attended by mourners the record was released posthumously, but the artwork had been chosen prior to Curtiss death. Reade believes that the Curtis myth grew primarily out of Joy Divisions music, which she describes as "between two worlds. Hearing [their music], one thinks they must be strange creatures with one step into the profound. Whereas in fact they were very down to earth.

At least some of the sources of the bands mystique are of this world as well: Factorys in-house producer Martin Hannett coached Curtiss vocals and infused the mix with spectral gravitas. And despite their intensely autobiographical nature, the lyrics were often influenced by literature and film. In Torn Apart, "Decades is used to support the case for Curtiss paranormal vision, but a different interpretation can be drawn from the songs original title, "Cross of Iron, namesake of a 1977 Sam Peckinpah film about WWII, told from the point of view of German soldiers. Its a logical connection, considering Curtiss fascination with Nazis "Joy Division was the name of sex-slavery wings in concentration camps. Despite the weight of his lore, and his possible aspiration to rocknroll canonization, Curtis wasnt the doomed, effete artist hes often made out to be. Even Reade who witnessed the depths of his depression when he lived with her for a brief period prior to his death adds to the chorus of onetime acquaintances, friends and family, who delight in debunking the myth with tales of laddish pranks and juvenile pre-occupations. "Ian Curtis was light-hearted, she says. "Just because it was cut short doesnt negate the fact he had a very happy life.

I am my own parasite

"And hes the one who likes all our pretty songs And he likes to sing along And he likes to shoot his gun But he dont know what it means.

From "In Bloom by Nirvana

Kurt Cobains complex nature is explored in a new documentary called About a Son, composed almost exclusively of present-day footage of the three Washington state towns that Nirvanas front-man once called home. Its a reverent device, with a teary soundtrack and sentimental finale, but Cobains frank, feature-length narration is a grounding counterpoint. The recordings were culled from 25 hours of taped interviews conducted by Michael Azerrad, author of the 1993 Nirvana biography Come As You Are, and producer of About a Son. "What the film does is portray Kurt as what he was, says Azerrad, "which was a human being full of intelligence and wit and anger and paranoia and sensitivity and arrogance and denial and wisdom.

Though Cobains early rock idols were mainstream acts like Queen and Aerosmith, he aspired to punk even before he heard it, essentially creating the style for himself based on descriptions in Creem magazine. When he moved from working class Aberdeen to the bohemian oasis of Olympia, he became consumed by the towns anti-corporate ethos. Its top two indie labels are Kill Rock Stars and K, and out of respect, Cobain had "K tattooed on his left arm, the one he played guitar with. Shortly thereafter, presumably with his other hand, he collected a fat advance from Geffen.

"I see his life as a battle between the values of the cool kids in Olympia and the guy who wanted to become a rock star in Aberdeen, says About a Son director A.J. Schnack. "He just didnt live long enough to resolve that conflict. One review of the film refers to Cobain as "the last rock star. He recognized that rock was on its last legs (as far as artistic innovation and mainstream popularity were concerned), and that the industry was overrun with pimps, yet he was driven to put out one last time. "In Bloom seems to capture Cobains malaise, criticizing fans attracted to his bands pop melodies in a song thats essentially one long, catchy chorus. Nirvana werent the only band drawing from the then-disparate realms of pop and punk, but through some serendipitous collision of good tunes, good timing and good looks, it was Nirvana that triumphed, hurtling from poverty to stardom in a matter of months. Managing newfound fame and a hefty workload was no cakewalk considering Cobains anti-social neuroses and chronic stomach pain, a hereditary condition that doctors were unable to diagnose. Cobain chose to treat himself with smack, and his new wife Courtney Love took the opportunity to indulge a Sid and Nancy fantasy.

And thats when the media descended. Love had unknowingly shot up during the first trimester of a pregnancy and immediately checked into detox, where Seattle hospital staff tipped off the press and child services. Roughly nine months later, one British tabloid ran with a cover story about the debauched parents and a photo of a crack baby. The fact that Frances Bean had been born healthy didnt stop the negative publicity, and the couple briefly lost custody of their child. The celebrity nosedive formula dictates that it was all downhill from there, that every day was soured by filth and lucre, by the dual horrors of heroin and fame. But its too easy to deem all drug use tragic and portray all stars as victims. Cobain wasnt groomed for life in the spotlight, but he actively pursued stardom and even found time to enjoy his achievements, regardless of his reservations.

"People have allowed his turbulent last few months, which were marred by violence and drug addiction and great unhappiness and a suicide attempt, to colour their perception of what kind of a man he was, says Azerrad, "and thats the whole purpose of About a Son, to correct that. The film also lays out the reasons why Cobain would later kill himself. Like his journals and his lyrics, his narration is dotted with references to a deeply rooted death wish, and he makes his motives plain: mental and physical anguish, and disillusionment with the life hed chosen. Azerrad stresses that Cobain did choose death, that the lingering murder theories fingering Love arose from the same kind of denial that spawned Elvis sightings. "People felt a very strong personal attachment to Kurt, and when he took his own life, some of his fans refused to believe it. Its a kind of mass delusion. We dont want your fucking love

"Jam your brain with broken heroes Love your masks and adore your failure "Clinging to your own sense of waste All we love is lonely wreckage

From "Stay Beautiful by Manic Street Preachers

Radicalized by the socialist fervour and "soul-destroying boredom and violence of south Wales, the Manic Street Preachers (aka the Manics) emerged as a flashy fusion of punk nihilism, political militancy and glam trash. As their co-lyricist and minister of propaganda, Richey Edwards openly endorsed self-destruction, and had a long list of mentally ill, suicidal idols, including Curtis and Cobain. That said, shortly before his disappearance from a London hotel in February 1995, he stated that he was stronger than suicide. But regardless of his many strengths, it was his weaknesses that attracted a following. "Depression and self-harm are crippling conditions, they arent cool or romantic, says Simon Price, a music journalist who wrote a Manics biography called Everything in 1999, and who witnessed the fall of the man and the rise of the martyr. "There exists a cult who cling to Richeys every word and action, and desperately try to interpret some sort of meaning in whatever he said or did, however trivial. In 1991, shortly before the Manics released their debut album, Generation Terrorists, Edwards carved the words "4 REAL into his arm to demonstrate his bands integrity for sceptical journalist Steve Lamacq. The image has become easy fodder for the British press, making magazine covers even a decade later. But it wasnt intended as a publicity stunt, and as gory as it appears, everyone in the Manics camp thought "4 REAL was a brilliant statement, including Price. However, Edwards was never particularly proud of his wounds or scars, as some members of his cult seem to believe.

"He found them amusing, in a self-deprecating sort of way, says Price. "I remember sharing a train journey with Richey shortly after the incident, and he showed me the still-pink, vivid scars and joked about it. It wasnt in a spirit of Look how cool I am, more a spirit of Look how stupid I was the other day. As Edwards developed a taste for rock-star excess, alcoholism and anorexia began to exacerbate his depression and self-mutilation. The more his troubles were reflected in his lyrics culminating in the Manics bleak and depraved 1994 album, The Holy Bible the more fans began to engage in what Price characterizes as "the fetishising of despair. On one occasion in Bangkok, a particularly voyeuristic follower even encouraged Edwards to cut himself during a show, giving him a set of ceremonial knives with a note reading, "Look at me while you do it. In his book, Price admits to a feeling of culpability, alongside other Manics fans, for their collective fascination with Edwards visible unravelling. He had appeared increasingly gaunt during his final tours, and in his last photo shoot, his shaved head and striped pajamas evoked victims of the Holocaust (a frequent lyrical muse) he also wore shoes identical to those found on Cobains corpse nine months earlier, and that was no coincidence. In the end, he came to embody the kind of "lonely wreckage hed once written about, and it was hard to look away. Edwards may have worn a guitar very well, but he didnt play on Manics records, and even on stage, he was buried in the mix. Feelings of inadequacy and overexposure, combined with the frightening devotion of the fans and the complete absence of a life outside the band, created a constraint from which the only option was escape. With his mysterious exit, he earned the same brand of idolatry and infamy as his "broken heroes. But thats cold comfort for those who knew him and fear the worst. "He understood the power of iconography better than anyone, says Price, "but by the time of his disappearance, Im afraid such considerations were far from the forefront of his mind.

Its the fame made a brother change

"Death is for a son to stay free. Im thugged out. Fuck the world cuz this is how they made me. Scarred but still breathin. Believe in me and you could see the victory. A warrior with jewels. Can you picture me?

"Life of an Outlaw by Tupac Shakur

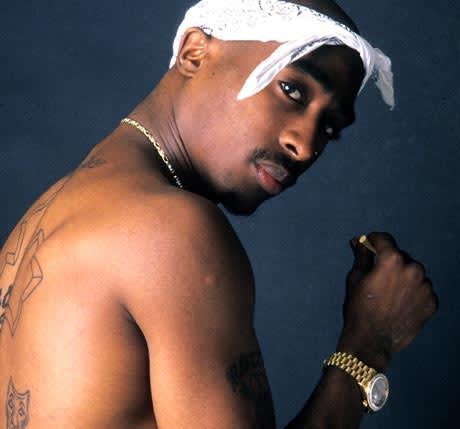

Second only to Elvis in posthumous record sales, Tupac Shakur is the most successful, least understood rapper of all time. As easy to dismiss as he is to venerate, some deem him a misogynist thug, others a black Jesus. Analysed in American universities and immortalised by wishful thinkers who say he faked his death, hes also hip-hops James Dean, an international poster boy for a disaffected generation. But in many ways, hes more akin to Che Guevara, a flawed revolutionary revered via millions of t-shirts while his socio-political ethos is left out to dry. Davey D, a hip-hop historian and radio personality who got to know Shakur on and off the air, feels that Shakurs legacy of activism is largely forgotten. "2Pac has become a money-making institution and a marketing tool for a lot of folks, he says, "but he had a lot of heart, and very few people who ride for Pac have embraced that part of him. Raised by a former Black Panther on the East coast, Shakurs poverty and a middle-class arts education sparked his ambition and his work ethic in interviews and in poetry, he described himself as a "rose that grew from concrete. He eventually found fame and fortune in California, and his roles in films such as Juice and Gang Related were as packed with portent as his rhymes. Shakurs wealth of premonitory lyrics range from wondering how long hed be mourned to asking Gods forgiveness for his "plan to die. Michael Eric Dyson, author of 2001s Holler If You Hear Me, has characterized this dwelling on doom as self-fulfilling prophecy, a "rush to the grave.

The glamorisation of Shakurs fatal shooting in September 1996 is a staple of nearly all the dozen-or-so 2Pac documentaries; cruise-speed dolly shots roll up to his assassination spot on the Vegas strip almost as often as the camera lingers on his famous abs. The filmmakers tend to choose one of two popular narratives to explain his unsolved murder, implicating either Suge Knight, head of Shakurs record label, Death Row, or Biggie Smalls (aka Notorious B.I.G.), who was himself gunned down six months later. Unfortunately, neither theory is likely to be pursued further due to the bungling of the initial investigation. Davey D dispels the notion that the famous coastal feud has any bearing on the case. Shakurs anger towards his New York counterparts, vented on tracks like "Hit Em Up, was spurred by his belief that Smalls and Sean "Puffy Combs (aka P Diddy) orchestrated his earlier shooting in 1994. This accusation has been widely discounted, but at the time it heightened an already brewing rivalry between artists and record companies on the East and West coasts. The media was quick to exploit and enable the war of words, as theyd already pounced on Shakurs every apparent misdeed.

D believes that Shakurs threats were intended (and recognised) as humiliation rather than a forewarning of actual vengeance broadcasting murderous intent isnt a typical criminal tactic. Perhaps Shakur wasnt as "real in this respect as his boasts made out, but he had other aspirations to street credibility: he wanted to form an East coast chapter of Death Row, he advocated codes of honour and peace zones for gangs as well as unions for prisoners, and he threatened to use his fan base to disrupt elections to win political concessions, which has led to suspicions of a higher-reaching murder conspiracy. As for Shakurs criminal record, he escaped conviction for the attempted murder of a pair of cops, but was later jailed on a bogus sexual abuse charge. Crime was inherent in "Thug Life, which he defined as a diagnosis of the young black male condition, though he eventually disowned the term due to its widespread misuse. "If you do wanna live a thug life and a gangsta life, okay, said Shakur, "so stop being cowards and lets have a revolution. Many speculate that Shakur was destined for leadership, and that the hip-hop community has failed to produce such a mover and a mind since his demise. Quincy Jones, whose daughter briefly dated Shakur, and whos been trying to get a 2Pac biopic off the ground, has spoken of Shakurs squandered potential in the same breath as Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. "He was kicking up dust and causing a certain commotion with the end goal of bringing about change, states D. But Shakurs descent into gang life seemed to contradict his social conscience, and may have sidetracked him in the end, even if hed lived.

The old Christian chestnut "he died for our sins arises with surprising ease in profiles of dead musicians, and Ian Curtis, Kurt Cobain, Richey Edwards and Tupac Shakur left behind no shortage of birds eye poetry, stained by Biblical brutality, to fuel their ascendance as icons. But this brand of reverence often breeds misconceptions and glorifies weakness, which does a disservice to the artists memory, and perhaps even perpetuates a tragic cycle. Doom-laden art is authenticated by an artists demise, but quixotic quests to keep it real can actually hasten their downfall. For these four men, that meant either wallowing in the wake of their own unfortunate idols, overexposing their suffering (attracting both like-minded fans and an invasive media), or striving to live up to the ideals of street credibility put forth by punk rock and hip-hop. These are complex characters blessed with talent, but cursed with irreconcilable dualities and other inner turmoil that stymied their rebellious nature and drove them into the ground. And the more their flaws are trivialized, glamorised or confused by myth, the more sad souls may follow them, taking strange comfort in precedent.

The past is now part of my future

"Watched from the wings as the scenes were replaying, We saw ourselves now as we never had seen Portrayal of the trauma and degeneration The sorrows we suffered and never were free.

From "Decades by Joy Division

In life, Ian Curtis was the leader of a mildly successful post-punk band, as well as a husband, father, boyfriend and job centre employee. In death, his band Joy Division has become legendary, perhaps never more popular and influential than they are now, due in part to mounting depictions of its singers suffering, cast in shadows of classic mythology.

Though the media has occasionally treated Curtis to such epithets as "saddo who couldnt hack it, the rumour that he may have "died for you began to emerge in his obituaries. Beneath the hype, and strewn across Curtiss lyrics, are the more humdrum motivations for his suicide in May 1980: guilt over the break-up of his family, and depression exacerbated by crude epilepsy meds. Although his ambition may have been stunted by his illnesses, and what biographer Lindsay Reade calls a "fear of the next level his death occurred on the eve of what would have been Joy Divisions first North American tour it could be argued that the appeal of posterity was never far from his mind.

In her 1995 memoir, Touching From a Distance, Deborah Curtis wrote about her late husbands predilection for artists who died young, and his expressed desire to follow suit. This revelation arises in Michael Winterbottoms 2002 film, 24 Hour Party People, in which Curtis is part of the larger story of Manchesters Factory Records and its founder, the late Tony Wilson. One scene finds Curtis disagreeing with Wilsons opinion that artists often produce their best work in old age. Wilson mentions W.B. Yeats, an unfamiliar name to Curtis, who says he would have heard of him if hed died by 25. In a later scene, he walks past a Doors poster in his house, an allusion to his idolatry of Jim Morrison.

"Perhaps he did crave the romantic mythology, says Reade, who was married to Wilson during Factorys early days, as portrayed in 24 Hour Party People. Torn Apart, a chronicle of Curtiss life in and out of the band, co-authored by Reade and Mick Middles, also addresses allegations of the singers clairvoyance and mediumship, traits historically ascribed to epileptics (as is demonic possession, though no one has yet to make that claim). "Something was going on with him that people were unaware of, she says. Next to Morrisons death by decadence in a Parisian bathtub, Curtiss hanging in his humble Macclesfield kitchen is decidedly devoid of glamour, yet its hit the silver screen twice, most recently in Control, a conventional Curtis biopic rendered in gorgeous black and white by onetime Joy Division photographer Anton Corbijn. Film audiences have also been privy to Curtiss "fits and the "dead fly dance that appears to simulate them. Though his affliction was kept secret, contemporary critics remarked on the resemblance between Curtiss trademark moves and epileptic seizures, as did Deborah, who witnessed both firsthand. Its even been suggested that he purposely triggered his on-stage seizures, which is hard to reconcile with the horrified feelings he expressed on these few occasions. But in an Under Review documentary that speculates on this subject, a clip from one of Curtiss few recorded interviews is played: "Instead of just singing about something, you can actually show it as well. Theres no need to just simulate when you can put it over the way it is. Considering the relative scarcity of documentation of Curtiss life and work, theres a surprising abundance of strangely telling detail surrounding his death: the last movie he watched (Werner Herzogs Stroszek, about a disastrous American venture by a band of European misfits), the last record he listened to (Iggy Pops The Idiot), the book his girlfriend was reading at the time (also The Idiot, by Dostoyevsky, about a saintly epileptic), the song his wife dreamt about the morning he died ("The End, by the Doors) and the sleeve design of Closer, depicting a dead Christ figure attended by mourners the record was released posthumously, but the artwork had been chosen prior to Curtiss death. Reade believes that the Curtis myth grew primarily out of Joy Divisions music, which she describes as "between two worlds. Hearing [their music], one thinks they must be strange creatures with one step into the profound. Whereas in fact they were very down to earth.

At least some of the sources of the bands mystique are of this world as well: Factorys in-house producer Martin Hannett coached Curtiss vocals and infused the mix with spectral gravitas. And despite their intensely autobiographical nature, the lyrics were often influenced by literature and film. In Torn Apart, "Decades is used to support the case for Curtiss paranormal vision, but a different interpretation can be drawn from the songs original title, "Cross of Iron, namesake of a 1977 Sam Peckinpah film about WWII, told from the point of view of German soldiers. Its a logical connection, considering Curtiss fascination with Nazis "Joy Division was the name of sex-slavery wings in concentration camps. Despite the weight of his lore, and his possible aspiration to rocknroll canonization, Curtis wasnt the doomed, effete artist hes often made out to be. Even Reade who witnessed the depths of his depression when he lived with her for a brief period prior to his death adds to the chorus of onetime acquaintances, friends and family, who delight in debunking the myth with tales of laddish pranks and juvenile pre-occupations. "Ian Curtis was light-hearted, she says. "Just because it was cut short doesnt negate the fact he had a very happy life.

I am my own parasite

"And hes the one who likes all our pretty songs And he likes to sing along And he likes to shoot his gun But he dont know what it means.

From "In Bloom by Nirvana

Kurt Cobains complex nature is explored in a new documentary called About a Son, composed almost exclusively of present-day footage of the three Washington state towns that Nirvanas front-man once called home. Its a reverent device, with a teary soundtrack and sentimental finale, but Cobains frank, feature-length narration is a grounding counterpoint. The recordings were culled from 25 hours of taped interviews conducted by Michael Azerrad, author of the 1993 Nirvana biography Come As You Are, and producer of About a Son. "What the film does is portray Kurt as what he was, says Azerrad, "which was a human being full of intelligence and wit and anger and paranoia and sensitivity and arrogance and denial and wisdom.

Though Cobains early rock idols were mainstream acts like Queen and Aerosmith, he aspired to punk even before he heard it, essentially creating the style for himself based on descriptions in Creem magazine. When he moved from working class Aberdeen to the bohemian oasis of Olympia, he became consumed by the towns anti-corporate ethos. Its top two indie labels are Kill Rock Stars and K, and out of respect, Cobain had "K tattooed on his left arm, the one he played guitar with. Shortly thereafter, presumably with his other hand, he collected a fat advance from Geffen.

"I see his life as a battle between the values of the cool kids in Olympia and the guy who wanted to become a rock star in Aberdeen, says About a Son director A.J. Schnack. "He just didnt live long enough to resolve that conflict. One review of the film refers to Cobain as "the last rock star. He recognized that rock was on its last legs (as far as artistic innovation and mainstream popularity were concerned), and that the industry was overrun with pimps, yet he was driven to put out one last time. "In Bloom seems to capture Cobains malaise, criticizing fans attracted to his bands pop melodies in a song thats essentially one long, catchy chorus. Nirvana werent the only band drawing from the then-disparate realms of pop and punk, but through some serendipitous collision of good tunes, good timing and good looks, it was Nirvana that triumphed, hurtling from poverty to stardom in a matter of months. Managing newfound fame and a hefty workload was no cakewalk considering Cobains anti-social neuroses and chronic stomach pain, a hereditary condition that doctors were unable to diagnose. Cobain chose to treat himself with smack, and his new wife Courtney Love took the opportunity to indulge a Sid and Nancy fantasy.

And thats when the media descended. Love had unknowingly shot up during the first trimester of a pregnancy and immediately checked into detox, where Seattle hospital staff tipped off the press and child services. Roughly nine months later, one British tabloid ran with a cover story about the debauched parents and a photo of a crack baby. The fact that Frances Bean had been born healthy didnt stop the negative publicity, and the couple briefly lost custody of their child. The celebrity nosedive formula dictates that it was all downhill from there, that every day was soured by filth and lucre, by the dual horrors of heroin and fame. But its too easy to deem all drug use tragic and portray all stars as victims. Cobain wasnt groomed for life in the spotlight, but he actively pursued stardom and even found time to enjoy his achievements, regardless of his reservations.

"People have allowed his turbulent last few months, which were marred by violence and drug addiction and great unhappiness and a suicide attempt, to colour their perception of what kind of a man he was, says Azerrad, "and thats the whole purpose of About a Son, to correct that. The film also lays out the reasons why Cobain would later kill himself. Like his journals and his lyrics, his narration is dotted with references to a deeply rooted death wish, and he makes his motives plain: mental and physical anguish, and disillusionment with the life hed chosen. Azerrad stresses that Cobain did choose death, that the lingering murder theories fingering Love arose from the same kind of denial that spawned Elvis sightings. "People felt a very strong personal attachment to Kurt, and when he took his own life, some of his fans refused to believe it. Its a kind of mass delusion. We dont want your fucking love

"Jam your brain with broken heroes Love your masks and adore your failure "Clinging to your own sense of waste All we love is lonely wreckage

From "Stay Beautiful by Manic Street Preachers

Radicalized by the socialist fervour and "soul-destroying boredom and violence of south Wales, the Manic Street Preachers (aka the Manics) emerged as a flashy fusion of punk nihilism, political militancy and glam trash. As their co-lyricist and minister of propaganda, Richey Edwards openly endorsed self-destruction, and had a long list of mentally ill, suicidal idols, including Curtis and Cobain. That said, shortly before his disappearance from a London hotel in February 1995, he stated that he was stronger than suicide. But regardless of his many strengths, it was his weaknesses that attracted a following. "Depression and self-harm are crippling conditions, they arent cool or romantic, says Simon Price, a music journalist who wrote a Manics biography called Everything in 1999, and who witnessed the fall of the man and the rise of the martyr. "There exists a cult who cling to Richeys every word and action, and desperately try to interpret some sort of meaning in whatever he said or did, however trivial. In 1991, shortly before the Manics released their debut album, Generation Terrorists, Edwards carved the words "4 REAL into his arm to demonstrate his bands integrity for sceptical journalist Steve Lamacq. The image has become easy fodder for the British press, making magazine covers even a decade later. But it wasnt intended as a publicity stunt, and as gory as it appears, everyone in the Manics camp thought "4 REAL was a brilliant statement, including Price. However, Edwards was never particularly proud of his wounds or scars, as some members of his cult seem to believe.

"He found them amusing, in a self-deprecating sort of way, says Price. "I remember sharing a train journey with Richey shortly after the incident, and he showed me the still-pink, vivid scars and joked about it. It wasnt in a spirit of Look how cool I am, more a spirit of Look how stupid I was the other day. As Edwards developed a taste for rock-star excess, alcoholism and anorexia began to exacerbate his depression and self-mutilation. The more his troubles were reflected in his lyrics culminating in the Manics bleak and depraved 1994 album, The Holy Bible the more fans began to engage in what Price characterizes as "the fetishising of despair. On one occasion in Bangkok, a particularly voyeuristic follower even encouraged Edwards to cut himself during a show, giving him a set of ceremonial knives with a note reading, "Look at me while you do it. In his book, Price admits to a feeling of culpability, alongside other Manics fans, for their collective fascination with Edwards visible unravelling. He had appeared increasingly gaunt during his final tours, and in his last photo shoot, his shaved head and striped pajamas evoked victims of the Holocaust (a frequent lyrical muse) he also wore shoes identical to those found on Cobains corpse nine months earlier, and that was no coincidence. In the end, he came to embody the kind of "lonely wreckage hed once written about, and it was hard to look away. Edwards may have worn a guitar very well, but he didnt play on Manics records, and even on stage, he was buried in the mix. Feelings of inadequacy and overexposure, combined with the frightening devotion of the fans and the complete absence of a life outside the band, created a constraint from which the only option was escape. With his mysterious exit, he earned the same brand of idolatry and infamy as his "broken heroes. But thats cold comfort for those who knew him and fear the worst. "He understood the power of iconography better than anyone, says Price, "but by the time of his disappearance, Im afraid such considerations were far from the forefront of his mind.

Its the fame made a brother change

"Death is for a son to stay free. Im thugged out. Fuck the world cuz this is how they made me. Scarred but still breathin. Believe in me and you could see the victory. A warrior with jewels. Can you picture me?

"Life of an Outlaw by Tupac Shakur

Second only to Elvis in posthumous record sales, Tupac Shakur is the most successful, least understood rapper of all time. As easy to dismiss as he is to venerate, some deem him a misogynist thug, others a black Jesus. Analysed in American universities and immortalised by wishful thinkers who say he faked his death, hes also hip-hops James Dean, an international poster boy for a disaffected generation. But in many ways, hes more akin to Che Guevara, a flawed revolutionary revered via millions of t-shirts while his socio-political ethos is left out to dry. Davey D, a hip-hop historian and radio personality who got to know Shakur on and off the air, feels that Shakurs legacy of activism is largely forgotten. "2Pac has become a money-making institution and a marketing tool for a lot of folks, he says, "but he had a lot of heart, and very few people who ride for Pac have embraced that part of him. Raised by a former Black Panther on the East coast, Shakurs poverty and a middle-class arts education sparked his ambition and his work ethic in interviews and in poetry, he described himself as a "rose that grew from concrete. He eventually found fame and fortune in California, and his roles in films such as Juice and Gang Related were as packed with portent as his rhymes. Shakurs wealth of premonitory lyrics range from wondering how long hed be mourned to asking Gods forgiveness for his "plan to die. Michael Eric Dyson, author of 2001s Holler If You Hear Me, has characterized this dwelling on doom as self-fulfilling prophecy, a "rush to the grave.

The glamorisation of Shakurs fatal shooting in September 1996 is a staple of nearly all the dozen-or-so 2Pac documentaries; cruise-speed dolly shots roll up to his assassination spot on the Vegas strip almost as often as the camera lingers on his famous abs. The filmmakers tend to choose one of two popular narratives to explain his unsolved murder, implicating either Suge Knight, head of Shakurs record label, Death Row, or Biggie Smalls (aka Notorious B.I.G.), who was himself gunned down six months later. Unfortunately, neither theory is likely to be pursued further due to the bungling of the initial investigation. Davey D dispels the notion that the famous coastal feud has any bearing on the case. Shakurs anger towards his New York counterparts, vented on tracks like "Hit Em Up, was spurred by his belief that Smalls and Sean "Puffy Combs (aka P Diddy) orchestrated his earlier shooting in 1994. This accusation has been widely discounted, but at the time it heightened an already brewing rivalry between artists and record companies on the East and West coasts. The media was quick to exploit and enable the war of words, as theyd already pounced on Shakurs every apparent misdeed.

D believes that Shakurs threats were intended (and recognised) as humiliation rather than a forewarning of actual vengeance broadcasting murderous intent isnt a typical criminal tactic. Perhaps Shakur wasnt as "real in this respect as his boasts made out, but he had other aspirations to street credibility: he wanted to form an East coast chapter of Death Row, he advocated codes of honour and peace zones for gangs as well as unions for prisoners, and he threatened to use his fan base to disrupt elections to win political concessions, which has led to suspicions of a higher-reaching murder conspiracy. As for Shakurs criminal record, he escaped conviction for the attempted murder of a pair of cops, but was later jailed on a bogus sexual abuse charge. Crime was inherent in "Thug Life, which he defined as a diagnosis of the young black male condition, though he eventually disowned the term due to its widespread misuse. "If you do wanna live a thug life and a gangsta life, okay, said Shakur, "so stop being cowards and lets have a revolution. Many speculate that Shakur was destined for leadership, and that the hip-hop community has failed to produce such a mover and a mind since his demise. Quincy Jones, whose daughter briefly dated Shakur, and whos been trying to get a 2Pac biopic off the ground, has spoken of Shakurs squandered potential in the same breath as Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. "He was kicking up dust and causing a certain commotion with the end goal of bringing about change, states D. But Shakurs descent into gang life seemed to contradict his social conscience, and may have sidetracked him in the end, even if hed lived.