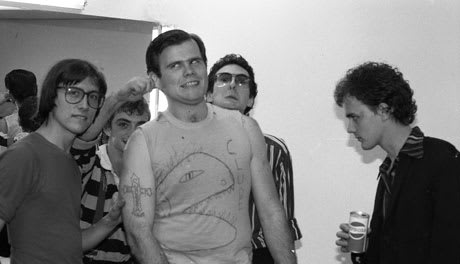

A bubbling crowd bounces at the front of the stage as the first raw, pop-addled lick chokes out across Torontos Horseshoe Tavern. Fists rise up in time to the beat and panting shouts are heard as fans add their voices to the chorus. It could be any punk gig in the country, but this isnt just another show. Its part of an onslaught of concerts the recently resurrected Pointed Sticks have played since calling it quits in 1981, and only the second time the Pointed Sticks performed in Toronto ever.

Before the show, front-man Nick Jones speaks excitedly about playing Toronto; Canadian geography being notoriously unfriendly to touring, the Sticks previous road adventures stuck close to their Vancouver home, up and down the West coast. But it wasnt just distance working against them, there was a distinct hostility towards punk when it emerged on the late 70s Canadian music landscape. While Torontos Viletones grabbed headlines like "Not Them, Not Here, the Pointed Sticks just felt invisible.

"It was more like If we ignore them, theyll go away, Jones says. "We never even got the Not Them, Not Here to even stir that kind of controversy. They thought that if they just ignored us, they could force us to go away. They didnt. Well, actually, they did, for a couple of decades anyway. But now, as punk celebrates its 30th anniversary this year, Canadian punk is returning with a vengeance.

"There seems to be something in the air that a lot of these people are getting back together, says drummer John Hamilton of the Diodes. "Its like youve been summoned, like a genie. Someones rubbed the magic lamp and youve been brought back.

On the West coast, the Modernettes and Van Citys first punk band the Furies both reclaimed the stage this year. In Toronto, the clashing sounds of the Viletones and Diodes are being reissued, and former members of the B-Girls, Johnny and the G-Rays and Zro4 have been seen on stage. In Montreal, indie label Soniks Chicken Shrimp is releasing its own local punk and hardcore legacies.

Yet there is a bittersweet undertone to these second-time-around celebrations. Perpetual disappointment plagued many Canadian punk bands, and despite the fact that this home-grown movement spawned the first three all-female punk acts in North America (the Curse, the B-Girls, and the Dishrags); opened doors for future generations of musicians; and bred seminal acts like D.O.A. and the Forgotten Rebels, there was an unapologetic hostility to the punk ethos and Canadian pioneers have almost never received their due. That hostility emanated from the music scene, the industry and media, and early punk circles remained powerful but small, with little hope of finding strength in numbers. Each of Canadas punk scenes developed in virtual isolation from one another. "We always assumed people would have forgotten, according to Ralph Alfonso, who started managing the Diodes in 1977.

Although labels like Other Peoples Music and Zulu Records unearthed and reissued some Canadian punk in 90s, there seems to be more momentum this time. Historically minded archivists are keen to chronicle this lost history. Colin Bruntons documentary The Last Pogo Jumps Again, Chacha Cha Cha, a sequel to his cult film on what was then billed as the last punk show at the Horseshoe, is currently in production, as is Kebec Punk, a doc that will chronicle the Montreal scene.

Even in the late 70s, Toronto was a major tour destination; the city played host to the likes of the New York Dolls, Iggy Pop and Patti Smith, but it was in September 1976, when the Ramones played Torontos New Yorker Theatre, that the burgeoning punk influence took hold. In just 20 minutes of three-chord vehemence, they lit a spark for Canadian punks.

Talking to seminal members of the scene, there is an unbridled enthusiasm for that musical period, tempered by a serious sense of loss the landscape of our countrys contributions are littered with abandoned artefacts. Take the Viletones, for example. Their first single, "Screamin Fist, was a direct influence on Washington, DC hardcore band Bad Brains, and is referenced continuously in William Gibsons seminal novel Neuromancer. Their unforgettable live shows where singer Steven Leckie, then known as Nazi Dog, could mesmerise the crowd without singing a note as he carved deep gashes into his body caused quite a stir in Toronto the Good. Their grating noise and self-destructive performances got them that "Not Them, Not Here headline the morning after their debut.

The Viletones quickly became Torontos most infamous, and were poised to break out, but the Viletones never recorded a full-length album at their peak. Leckie has carried the Viletones legacy on his back ever since, and at 49, his tattooed body still bears the scars of those early days. He remains dedicated to his cause that Toronto get its just due along with London and New York as a birthplace of punk. "If Ive got anything to say about it, it will, he says. "Ill give it everything Ive got because thats all Ive got. And in a way thats kind of noble. It makes me feel like a Templar Knight and Ive got to go into battle.

These challenges were not unique to the Viletones or to Toronto. Media attention focussed on the most shocking and extreme elements of the punk scene, almost completely ignoring the music; in an interview for the CBC with Teenage Head, the Viletones and the Poles, reporter Hana Gartner told Teenage Head that all she got from their music was "a headache. Scarce live music venues were more interested in Top 40 cover bands, and the musicians union had a stranglehold on those that werent. The Diodes, whose crazed power pop helped establish the Toronto sound, quickly realised that if there were to be a punk scene, theyd have to create it themselves.

"Nobody would let you do anything, says drummer John Hamilton. "There was a fairly strong music business structure in place that was interested in keeping what they had.

"Most bands had management companies, all organised around this sort of late glitter, heavy metal thing that was going through Toronto: April Wine, Moxy, Goddo, adds Diodes bassist Ian Mackay. "They didnt know what to do with [punk].

Since there was no place to play, the Diodes opened the citys first punk club in the summer of 1977, the Crash n Burn, located in the bands basement rehearsal space. "Before Crash n Burn, we played wherever people would let us, and then more often than not, after the first gig they wouldnt let us come back because there were broken things, says B-Girls vocalist Lucasta Rochas. "We were kind of nomads going wherever anybody would let us. There were a couple of places that let us play pretty regularly but we always felt like we sort of had to abide by their rules. When we got the Crash n Burn together, it was like our place and we could do what we wanted. It was really exciting everyone pitched in and we were painting and doing carpentry and cleaning. It was our own.

For all its good intentions, the Crash n Burn lasted just four months, from May to August 1977. What started co-operatively soon devolved into anarchy; media attention that focussed on punks destructive tendencies was taken to heart by some scene newcomers, the club got out of hand and the Diodes were evicted from the space.

Almost immediately, the Diodes vaulted ahead of everyone else in the scene when they were offered what many desperately craved: a record deal. With the punk explosion in full force worldwide, CBS Canada was on the hunt for a domestic punk band. While it didnt take the band very far, it also seriously damaged the nascent scene; whatever sense of unity was captured at Crash n Burn quickly disintegrated into petty jealousies.

"We were almost forced to fragment off because we had to go play, says bassist Ian Mackay. "We had to go into the studio and record an album. We had to go nationwide. While we were at ground zero at the beginning, we in a sense disappeared from the scene. We had to. And there was a certain amount of rejection, too. People were saying Those guys? It should have been me.

As it turns out, there wasnt much to be jealous of. In the hands of CBS, the Diodes found themselves assigned to a management company that had no understanding and little interest in what they were trying to do. The Diodes were faced with not only breaking themselves as a band, but as a whole new sound to conservative radio stations, and they subsequently struggled to find a fan base. Only a year after signing, CBS dropped the Diodes.

The influence of punk is international, but in its earliest days, Canadian punks were completely isolated from one another. "We knew what was going on in Toronto, but it was easier for us to go play in California than it was for us to go and play in Toronto, explains Pointed Sticks Nick Jones. "I think the Vancouver scene, because we were so far away, it was a bit more autonomous because we didnt get all the bands coming through, so we didnt really have models that Toronto bands did. The Viletones, the Ugly, the B-Girls none of those bands ever made it out here.

Not everyone was daunted by the sprawling landscape. In 1977, Joey "Shithead Keithley and his band the Skulls (later to become D.O.A.) headed to Toronto. Theyd heard about CBGB in New York, the Masque in L.A., and the Crash n Burn in Toronto. But by the time they arrived in the midst of a massive winter storm the Crash n Burn was done. Abandoning initial plans to relocate to England, Keithley and gang headed back west to change the face of Canadian punk.

Undoubtedly one of Canadas best-known, most successful punks, Keithley tapped into the communal West coast vibe and DIY ethic to form Sudden Death Records, which is still actively interested in chronicling Canadas early history, despite scepticism from within the scene itself.

"I know the Vancouver people, a lot of them were like, Oh fuck, nobody will ever buy this stuff. Its dead, Keithley says. "So I had to convince a few of the bands. They didnt see the worth in it even as a historical document, given their unhappy departure in music. Thats what happens when you cant keep it going. Theres usually a sense of bitterness. As Modernettes front-man John Armstrong (aka Buck Cherry) points out, "rocknroll is not one of those things where you get special points for being there first or at the head of the pack. He compares the way these bands are now being discovered as similar to the way early blues artists were unearthed.

The Japanese market, for one, is eagerly embracing Canadian punk. Reissues of the Modernettes Get It Straight and the Pointed Sticks Wasted Youth and Waiting For the Real Thing have sold solidly overseas, and both bands have reunited for Japanese tours.

Today, Armstrong runs a group home and a recording studio he co-founded with the Pointed Sticks Gord Nicoll. And while, unlike the Viletones, both Vancouver bands have a recorded legacy to look back on, the nicest thing 30 years later is thinking that anyone still cares. "Its very gratifying, Armstrong says. "God knows nobody ever made any kind of money. Well, some people did, but not the musicians. We had the perfect level of not failure but not success; we were never big enough that it was worth anyone going after us to really rip us off.

By the early 80s, small scenes popped up all over Canada, and Montreals hardcore scene was particularly active, a legacy that local label Soniks Chicken Shrimp is actively uprooting. "I see this more as a hardcore comeback, mainly due to the book and movie American Hardcore, says label founder Mathieu Sonik. "The music is discovered by a new generation of kids here and all around the world too. Lots of good new bands are taking inspiration from the early `80s sound.

Rick Trembles was a member of a late 70s Montreal band the Electric Vomit before moving on to the American Devices, a quirky post-punk band that are still active. The first punk show he ever saw was the Viletones at Montreals Hotel Nelson, and he says Toronto bands were perceived "with some jealousy because they actually got coverage outside their own cities. There were bands just as newsworthy in Montreal, but they got completely ignored, probably because there werent any good enough writers around to champion them, and because nobody had the guts or spare cash to invest in releasing anything. Eventually a lot of major cities would have their own scenes, and the fact that Toronto had the Viletones was interesting because it felt like potential for Toronto to develop a sound of its own. I remember we thought that was the whole point of punk rock, that every city would have its own little scene and develop a sound of its own. [But] Montreal never got in the news, never got any recognition.

Unearthing musical obscurities is easier in an internet age, and now, Michel Gagnon of Quebecs Garbage Bag Records is pressing the Electric Vomits first demo on vinyl. "It took us only 30 years, but were finally getting released, Trembles says. "[Gagnon] is a huge fan of the most little-known 70s punk bands and when he found out about us, to him it was like hitting the jackpot. He put me back in touch with ex-members I hadnt heard from in decades. Were even toying with the idea of doing a reunion show for the occasion.

Not all the bands involved in this revival are faced with resurrecting long-dormant careers, unearthing long-lost band members or dusting off neglected recordings. Some, like Hamiltons Teenage Head, have remained mainstays on the Canadian punk scene for 30 years. Guitarist Gordie Lewis, for one, credits his peers for making a comeback and believes that age may actually be an advantage for some of these archetypal punks. "All I know is that if for some reason I was able to follow and pursue that passion, and then it was gone or taken away from me, I know that I would grab any opportunity that came my way to do it again, he says. "It would be something I would take full advantage of, and with the experience and knowledge of being older and more mature, hopefully I would have learned from all the mistakes and things I took for granted. Teenage Head emerged from singer Frankie Venoms basement (well, his parents basement, really) and played their first show in 1975. When the Toronto punk scene found its legs, Teenage Head found a perfect opportunity to showcase their Stooges/New York Dolls-inflected rocknroll. But even though they had a head start on other up-and-comers, Teenage Head didnt release a full-length album until 1979. And typically for the nascent Canadian music industry, appropriate venues simply werent available that self-titled debut came out on Inter Global Music, a disco label.

The inauspicious start wasnt the breakthrough they were looking for, but by the time their sophomore release, Frantic City, came out in 1980, Teenage Head were drawing crowds in the thousands. Sadly, popularity crunched head-on with the mainstreams preconceived notions of punks seediness when a now-legendary riot broke out at the Ontario Place Forum in 1980 when Head fans were turned away from the general-admission venue due to overcrowding. But regular airplay on mainstream rock radio like Torontos Q 107 had Teenage Head looking Stateside for a potential breakthrough. Just before heading to New York City for an important showcase, a devastating car crash left Gordie Lewis with a broken back. Momentum stalled for the band, but for Lewis, calling it quits was never an option. Theyve gone on hiatus occasionally, and there have been some line-up changes in the last 30 years, but they retain a sense of excitement, especially since Sonic Unyons reissue of their first album last year shed some new light on their contributions to Canadian punk. This year, they will finally release a long-gestating album they recorded with Marky Ramone in 2003.

"Weve kind of constantly been doing it, but for me originally, it was a musical passion that I had, Lewis says. "Its in your blood and itll always be there.

These bands have paid their proverbial dues. They changed the landscape of the Canadian music industry, and now many will face challenges just as daunting: how to translate all this to a younger audience today.

"Thats the big thing, really, says the Diodes Ian Mackay. "How do you sell yourself 30 years later as a mature individual in the context of punk rock, which really is a youth-oriented music? If we were jazz musicians, or folk they translate well into old age, or late middle age. But when you start to sing about youthful rebellion, it starts to feel a bit like a high school reunion. I think the main thing, though, is as long as the music comes through, nothing else really matters. Yeah, we might not have the same energy as we did, but the music was dynamic, had a lot of energy, and were trying our best to bring that back.

Before the show, front-man Nick Jones speaks excitedly about playing Toronto; Canadian geography being notoriously unfriendly to touring, the Sticks previous road adventures stuck close to their Vancouver home, up and down the West coast. But it wasnt just distance working against them, there was a distinct hostility towards punk when it emerged on the late 70s Canadian music landscape. While Torontos Viletones grabbed headlines like "Not Them, Not Here, the Pointed Sticks just felt invisible.

"It was more like If we ignore them, theyll go away, Jones says. "We never even got the Not Them, Not Here to even stir that kind of controversy. They thought that if they just ignored us, they could force us to go away. They didnt. Well, actually, they did, for a couple of decades anyway. But now, as punk celebrates its 30th anniversary this year, Canadian punk is returning with a vengeance.

"There seems to be something in the air that a lot of these people are getting back together, says drummer John Hamilton of the Diodes. "Its like youve been summoned, like a genie. Someones rubbed the magic lamp and youve been brought back.

On the West coast, the Modernettes and Van Citys first punk band the Furies both reclaimed the stage this year. In Toronto, the clashing sounds of the Viletones and Diodes are being reissued, and former members of the B-Girls, Johnny and the G-Rays and Zro4 have been seen on stage. In Montreal, indie label Soniks Chicken Shrimp is releasing its own local punk and hardcore legacies.

Yet there is a bittersweet undertone to these second-time-around celebrations. Perpetual disappointment plagued many Canadian punk bands, and despite the fact that this home-grown movement spawned the first three all-female punk acts in North America (the Curse, the B-Girls, and the Dishrags); opened doors for future generations of musicians; and bred seminal acts like D.O.A. and the Forgotten Rebels, there was an unapologetic hostility to the punk ethos and Canadian pioneers have almost never received their due. That hostility emanated from the music scene, the industry and media, and early punk circles remained powerful but small, with little hope of finding strength in numbers. Each of Canadas punk scenes developed in virtual isolation from one another. "We always assumed people would have forgotten, according to Ralph Alfonso, who started managing the Diodes in 1977.

Although labels like Other Peoples Music and Zulu Records unearthed and reissued some Canadian punk in 90s, there seems to be more momentum this time. Historically minded archivists are keen to chronicle this lost history. Colin Bruntons documentary The Last Pogo Jumps Again, Chacha Cha Cha, a sequel to his cult film on what was then billed as the last punk show at the Horseshoe, is currently in production, as is Kebec Punk, a doc that will chronicle the Montreal scene.

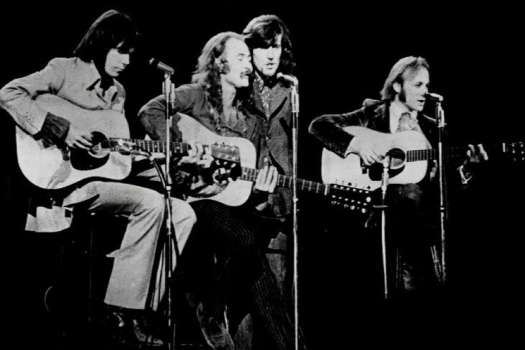

Even in the late 70s, Toronto was a major tour destination; the city played host to the likes of the New York Dolls, Iggy Pop and Patti Smith, but it was in September 1976, when the Ramones played Torontos New Yorker Theatre, that the burgeoning punk influence took hold. In just 20 minutes of three-chord vehemence, they lit a spark for Canadian punks.

Talking to seminal members of the scene, there is an unbridled enthusiasm for that musical period, tempered by a serious sense of loss the landscape of our countrys contributions are littered with abandoned artefacts. Take the Viletones, for example. Their first single, "Screamin Fist, was a direct influence on Washington, DC hardcore band Bad Brains, and is referenced continuously in William Gibsons seminal novel Neuromancer. Their unforgettable live shows where singer Steven Leckie, then known as Nazi Dog, could mesmerise the crowd without singing a note as he carved deep gashes into his body caused quite a stir in Toronto the Good. Their grating noise and self-destructive performances got them that "Not Them, Not Here headline the morning after their debut.

The Viletones quickly became Torontos most infamous, and were poised to break out, but the Viletones never recorded a full-length album at their peak. Leckie has carried the Viletones legacy on his back ever since, and at 49, his tattooed body still bears the scars of those early days. He remains dedicated to his cause that Toronto get its just due along with London and New York as a birthplace of punk. "If Ive got anything to say about it, it will, he says. "Ill give it everything Ive got because thats all Ive got. And in a way thats kind of noble. It makes me feel like a Templar Knight and Ive got to go into battle.

These challenges were not unique to the Viletones or to Toronto. Media attention focussed on the most shocking and extreme elements of the punk scene, almost completely ignoring the music; in an interview for the CBC with Teenage Head, the Viletones and the Poles, reporter Hana Gartner told Teenage Head that all she got from their music was "a headache. Scarce live music venues were more interested in Top 40 cover bands, and the musicians union had a stranglehold on those that werent. The Diodes, whose crazed power pop helped establish the Toronto sound, quickly realised that if there were to be a punk scene, theyd have to create it themselves.

"Nobody would let you do anything, says drummer John Hamilton. "There was a fairly strong music business structure in place that was interested in keeping what they had.

"Most bands had management companies, all organised around this sort of late glitter, heavy metal thing that was going through Toronto: April Wine, Moxy, Goddo, adds Diodes bassist Ian Mackay. "They didnt know what to do with [punk].

Since there was no place to play, the Diodes opened the citys first punk club in the summer of 1977, the Crash n Burn, located in the bands basement rehearsal space. "Before Crash n Burn, we played wherever people would let us, and then more often than not, after the first gig they wouldnt let us come back because there were broken things, says B-Girls vocalist Lucasta Rochas. "We were kind of nomads going wherever anybody would let us. There were a couple of places that let us play pretty regularly but we always felt like we sort of had to abide by their rules. When we got the Crash n Burn together, it was like our place and we could do what we wanted. It was really exciting everyone pitched in and we were painting and doing carpentry and cleaning. It was our own.

For all its good intentions, the Crash n Burn lasted just four months, from May to August 1977. What started co-operatively soon devolved into anarchy; media attention that focussed on punks destructive tendencies was taken to heart by some scene newcomers, the club got out of hand and the Diodes were evicted from the space.

Almost immediately, the Diodes vaulted ahead of everyone else in the scene when they were offered what many desperately craved: a record deal. With the punk explosion in full force worldwide, CBS Canada was on the hunt for a domestic punk band. While it didnt take the band very far, it also seriously damaged the nascent scene; whatever sense of unity was captured at Crash n Burn quickly disintegrated into petty jealousies.

"We were almost forced to fragment off because we had to go play, says bassist Ian Mackay. "We had to go into the studio and record an album. We had to go nationwide. While we were at ground zero at the beginning, we in a sense disappeared from the scene. We had to. And there was a certain amount of rejection, too. People were saying Those guys? It should have been me.

As it turns out, there wasnt much to be jealous of. In the hands of CBS, the Diodes found themselves assigned to a management company that had no understanding and little interest in what they were trying to do. The Diodes were faced with not only breaking themselves as a band, but as a whole new sound to conservative radio stations, and they subsequently struggled to find a fan base. Only a year after signing, CBS dropped the Diodes.

The influence of punk is international, but in its earliest days, Canadian punks were completely isolated from one another. "We knew what was going on in Toronto, but it was easier for us to go play in California than it was for us to go and play in Toronto, explains Pointed Sticks Nick Jones. "I think the Vancouver scene, because we were so far away, it was a bit more autonomous because we didnt get all the bands coming through, so we didnt really have models that Toronto bands did. The Viletones, the Ugly, the B-Girls none of those bands ever made it out here.

Not everyone was daunted by the sprawling landscape. In 1977, Joey "Shithead Keithley and his band the Skulls (later to become D.O.A.) headed to Toronto. Theyd heard about CBGB in New York, the Masque in L.A., and the Crash n Burn in Toronto. But by the time they arrived in the midst of a massive winter storm the Crash n Burn was done. Abandoning initial plans to relocate to England, Keithley and gang headed back west to change the face of Canadian punk.

Undoubtedly one of Canadas best-known, most successful punks, Keithley tapped into the communal West coast vibe and DIY ethic to form Sudden Death Records, which is still actively interested in chronicling Canadas early history, despite scepticism from within the scene itself.

"I know the Vancouver people, a lot of them were like, Oh fuck, nobody will ever buy this stuff. Its dead, Keithley says. "So I had to convince a few of the bands. They didnt see the worth in it even as a historical document, given their unhappy departure in music. Thats what happens when you cant keep it going. Theres usually a sense of bitterness. As Modernettes front-man John Armstrong (aka Buck Cherry) points out, "rocknroll is not one of those things where you get special points for being there first or at the head of the pack. He compares the way these bands are now being discovered as similar to the way early blues artists were unearthed.

The Japanese market, for one, is eagerly embracing Canadian punk. Reissues of the Modernettes Get It Straight and the Pointed Sticks Wasted Youth and Waiting For the Real Thing have sold solidly overseas, and both bands have reunited for Japanese tours.

Today, Armstrong runs a group home and a recording studio he co-founded with the Pointed Sticks Gord Nicoll. And while, unlike the Viletones, both Vancouver bands have a recorded legacy to look back on, the nicest thing 30 years later is thinking that anyone still cares. "Its very gratifying, Armstrong says. "God knows nobody ever made any kind of money. Well, some people did, but not the musicians. We had the perfect level of not failure but not success; we were never big enough that it was worth anyone going after us to really rip us off.

By the early 80s, small scenes popped up all over Canada, and Montreals hardcore scene was particularly active, a legacy that local label Soniks Chicken Shrimp is actively uprooting. "I see this more as a hardcore comeback, mainly due to the book and movie American Hardcore, says label founder Mathieu Sonik. "The music is discovered by a new generation of kids here and all around the world too. Lots of good new bands are taking inspiration from the early `80s sound.

Rick Trembles was a member of a late 70s Montreal band the Electric Vomit before moving on to the American Devices, a quirky post-punk band that are still active. The first punk show he ever saw was the Viletones at Montreals Hotel Nelson, and he says Toronto bands were perceived "with some jealousy because they actually got coverage outside their own cities. There were bands just as newsworthy in Montreal, but they got completely ignored, probably because there werent any good enough writers around to champion them, and because nobody had the guts or spare cash to invest in releasing anything. Eventually a lot of major cities would have their own scenes, and the fact that Toronto had the Viletones was interesting because it felt like potential for Toronto to develop a sound of its own. I remember we thought that was the whole point of punk rock, that every city would have its own little scene and develop a sound of its own. [But] Montreal never got in the news, never got any recognition.

Unearthing musical obscurities is easier in an internet age, and now, Michel Gagnon of Quebecs Garbage Bag Records is pressing the Electric Vomits first demo on vinyl. "It took us only 30 years, but were finally getting released, Trembles says. "[Gagnon] is a huge fan of the most little-known 70s punk bands and when he found out about us, to him it was like hitting the jackpot. He put me back in touch with ex-members I hadnt heard from in decades. Were even toying with the idea of doing a reunion show for the occasion.

Not all the bands involved in this revival are faced with resurrecting long-dormant careers, unearthing long-lost band members or dusting off neglected recordings. Some, like Hamiltons Teenage Head, have remained mainstays on the Canadian punk scene for 30 years. Guitarist Gordie Lewis, for one, credits his peers for making a comeback and believes that age may actually be an advantage for some of these archetypal punks. "All I know is that if for some reason I was able to follow and pursue that passion, and then it was gone or taken away from me, I know that I would grab any opportunity that came my way to do it again, he says. "It would be something I would take full advantage of, and with the experience and knowledge of being older and more mature, hopefully I would have learned from all the mistakes and things I took for granted. Teenage Head emerged from singer Frankie Venoms basement (well, his parents basement, really) and played their first show in 1975. When the Toronto punk scene found its legs, Teenage Head found a perfect opportunity to showcase their Stooges/New York Dolls-inflected rocknroll. But even though they had a head start on other up-and-comers, Teenage Head didnt release a full-length album until 1979. And typically for the nascent Canadian music industry, appropriate venues simply werent available that self-titled debut came out on Inter Global Music, a disco label.

The inauspicious start wasnt the breakthrough they were looking for, but by the time their sophomore release, Frantic City, came out in 1980, Teenage Head were drawing crowds in the thousands. Sadly, popularity crunched head-on with the mainstreams preconceived notions of punks seediness when a now-legendary riot broke out at the Ontario Place Forum in 1980 when Head fans were turned away from the general-admission venue due to overcrowding. But regular airplay on mainstream rock radio like Torontos Q 107 had Teenage Head looking Stateside for a potential breakthrough. Just before heading to New York City for an important showcase, a devastating car crash left Gordie Lewis with a broken back. Momentum stalled for the band, but for Lewis, calling it quits was never an option. Theyve gone on hiatus occasionally, and there have been some line-up changes in the last 30 years, but they retain a sense of excitement, especially since Sonic Unyons reissue of their first album last year shed some new light on their contributions to Canadian punk. This year, they will finally release a long-gestating album they recorded with Marky Ramone in 2003.

"Weve kind of constantly been doing it, but for me originally, it was a musical passion that I had, Lewis says. "Its in your blood and itll always be there.

These bands have paid their proverbial dues. They changed the landscape of the Canadian music industry, and now many will face challenges just as daunting: how to translate all this to a younger audience today.

"Thats the big thing, really, says the Diodes Ian Mackay. "How do you sell yourself 30 years later as a mature individual in the context of punk rock, which really is a youth-oriented music? If we were jazz musicians, or folk they translate well into old age, or late middle age. But when you start to sing about youthful rebellion, it starts to feel a bit like a high school reunion. I think the main thing, though, is as long as the music comes through, nothing else really matters. Yeah, we might not have the same energy as we did, but the music was dynamic, had a lot of energy, and were trying our best to bring that back.